The moment we realise we are pregnant follows the darker, larger news: the realisation of loss. K is in violent, harrowing pain and a pregnancy test confirms the best – and worst – news all at once. After years of trying for a baby, the silver lining flickers past as we swing between the comfort of achievement and no comfort at all.

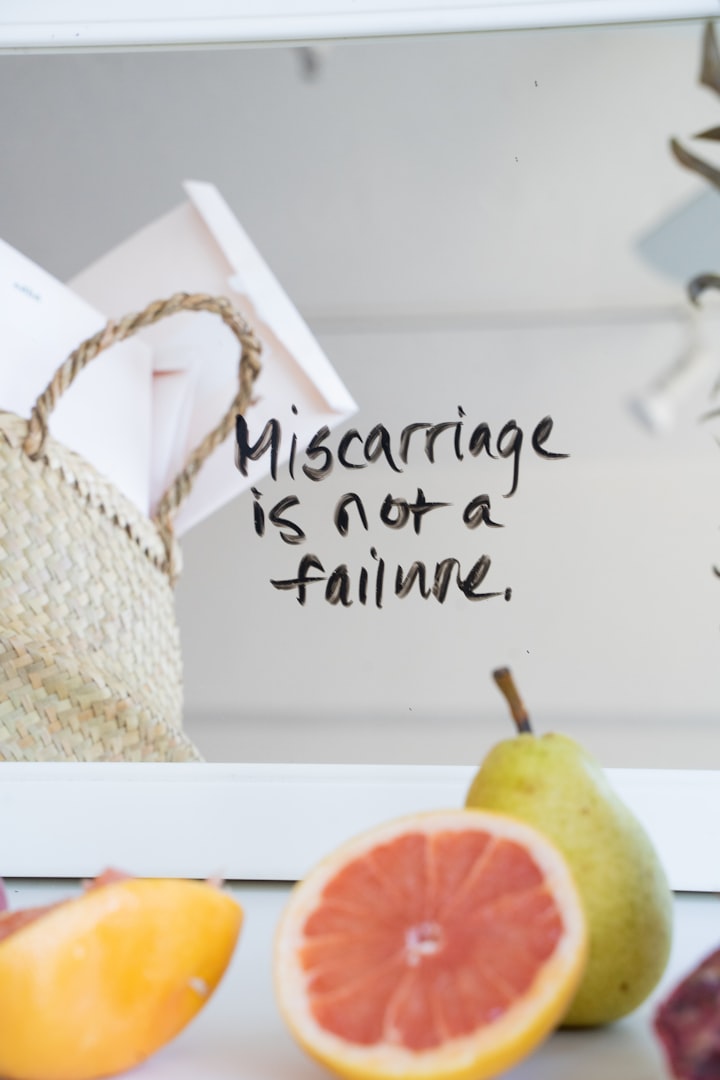

Those were the first moments of our miscarriage. The final moments – of what turned out to be a prolonged miscarriage – came a month later when K returned home from hospital on 11 September 2001. This is the tale of the intervening period and the years since. In particular, it is the anatomy of what turned out to be the distinguishing feature of almost every miscarriage: the fact that nobody wanted to know.

A UK Miscarriage Association survey of over 300 women who had suffered pregnancy loss found that only 29 percent of them felt well-cared for emotionally. Almost half - 45 percent – did not feel well informed about what was happening to them. Nearly four out of five – 79 percent – received absolutely no aftercare. A quarter of a million couples in the UK – one in five pregnancies – go through a miscarriage every year. The world is full of death and decay, but unless it happened on the news, it never happened at all.

K is the terrifying grey of dead skin, but somewhat upbeat and stoic about the pain as paramedics help her into the ambulance. We are all putting a brave face on, even though I’ve never got on with the practice since my father’s last reported words were flippant asides made in the back of an ambulance. I much prefer his penultimate speech, apparently slumping over a steering wheel with the prophetic, but unhelpful, “that’s it”. Curtains twitch in our quiet road. I take my place in the ambulance.

We enter the hospital by the back door of Maternity. A doctor sees us quickly but is sceptical about K’s condition. A little later, he apologizes when a hospital issue urine test confirms the result on our identical piss stick. Maybe he thought we forged ours with a felt tip, but the official verdict, apparently, is that she is ‘weakly pregnant’.

This sounds like something of a tactless fudge for a binary condition – a straight yes or no would have been fine – but countless blood tests over the next month show K’s levels of the pregnancy hormone HCG drifting up and down in a grey area between positive and negative. She knows she has miscarried, but her body still thinks it is pregnant and with good reason; it is. Doctors will continually emphasise, one slap in the face after another, that the pregnancy is “not viable”, though it hardly needs saying.

We sit in a grim, stygian waiting room. There are hardened varnished blu-tack droppings on unsecured carpet tiles, posters of disease and grief on the walls. The neon lighting and the faraway swish and bang of double doors are hypnotic and sickening. K has been admitted. She would rather be safe here than at home, a dozen miles away. We kiss goodnight and risk breaking the charm. We have been in a spell since all this started this afternoon. The panic and emergency have been a dizzying focus for us. Take that away and we are lost and alone.

At home at midnight, I don’t know what to do with myself. In a surprise move, I defrost our ancient fridge, turn it on and watch smoke pour out as it nearly catches fire. I must have done that wrong. I turn it off. I watch it for a full hour, fixated on its white door like a man who, at a stretch, only wants to deal with a single emergency a day. Eventually, because I don’t want to be consumed overnight in a bizarre fridge-fire accident, I heave it out into the backyard at one in the morning, only for it to it topple down steep concrete steps. I take the moment to observe my situation; that of a swearing insomniac flinching as his white goods rumble and clatter down the garden and wonder when someone will trouble themselves to call the police. I catch the reflection of my haunted scowl in the window and go to bed.

Up early the next morning it’s clear that, in all the panic, the fertility treatment process we began recently has been quietly side-lined. We have gone from casually ‘trying for a baby’ to the next step – one with the air of a more formal medical investigation, a process that aims to solve mysteries but dissolves dignity along the way.

Today is the day, of all days, that I am due at the hospital with my sperm sample. Today I have to fill a cup and let my boys be put through their paces in a manner, I imagine, that is the path-lab equivalent of an assault course. If my sperm were powered by irony, it’s a great day to give, but it seems tactless, somehow. Mind you, not as tactless as the consultant who was dropped onto K’s ward like a bewilderment-seeking bomb and, having learnt of my cancelled mission, attempts to jolly her along with the idea that maybe I wasn’t the father, after all. Thank you for that, we all feel entertained now.

I had to find explanations for anyone who needed to know or asked. It quickly became apparent that this was something you do not talk about. At all. Ever. Broaching it was taboo. Society used to treat the subjects of birth and death with the same kind of reverence. Ladies in labour were ‘in confinement’ and, at the other end of life, curtains were drawn in dignity for grief. The taboo of miscarriage has the potency of both as if they were somehow multiplied together. Nobody even says sorry. That’s if you see them face to face because, for the most part, we didn't.

We were ignored for months as if we suffered some kind of infectious disease or dirty secret. Many of those with their own families were the worst: dumbfounded by guilt, stricken silent harbouring their children like precious contraband, as if we had killed our own and were now coming after theirs.

K comes home from hospital at the weekend. She is tired and sick but being brave because she has no choice. It’s clear the doctors expect her body to complete the awful process without the benefit of medical intervention. She hasn’t stopped bleeding yet and her complexion is thin and haunted. This is the first time we’ve been alone together for four days and I don’t know what to make of it.

I move into a holding pattern, circling the subject, waiting for clearance to land. Thoughts freeze and turn abstract in a situation where thinking is not appropriate, arriving in little machine gun bursts, racing to catch up. I attempt to bend my mind around what has happened – is still happening – well aware that it’s beyond rational thought. I can’t surrender to the misery of it all and it seems self-indulgent to lose myself in loss with the fresh memory of K in pain.

She continues to lose blood and have positive pregnancy tests for the next two weeks. She is still at risk of haemorrhaging and is understandably frightened to be alone. Her parents pick her up every day an hour after I leave for work and look after her until I get home.

I started a new job – as a magazine production editor – about two weeks before the miscarriage began, but I’m already trapped in a high-pressure environment twenty-five miles from home and sometimes I don’t get back until late. I count my blessings that her parents help with shopping, feed her every night and even bring back pre-cooked food for me.

Today, Friday, we have an ultrasound appointment – our second – in the hospital’s Early Pregnancy Unit (EPU). The radiographer is looking for clues why K’s hormone levels still indicate she is technically pregnant. It has become a gynaecological game of Battleship: our target being what is euphemistically referred to as ‘material’ thought to be left over and responsible for the continuing positive pregnancy results.

The radiographer thinks she sees something near the neck of the womb, but the session is inconclusive and uneasy, and you can almost hear the doors closing on any discussion of what is happening. Once more, in this festival of pregnant pauses, things are left unsaid. A blood test shows a sharp rise in HCG and a doctor pointedly asks how far away we live. “Twelve miles”, he says, “that should be alright”. We leave for home feeling that life may suddenly take a turn.

Three weeks in and we're still waiting. Every twinge, pain and ache could be the start of something bigger any moment now. We spend a tense weekend scared rigid in front of the television. It was like taking a bomb home.

It is the following Thursday and I finally present my sample through a frosted glass sliding window in a wall of a lobby, behind a door, off a hallway, in the basement of the hospital. It was surprisingly easy to find. Meanwhile, this is a family occasion, and I meet K as she is ferried in by her mum for a slightly later appointment at the EPU.

The events of this morning and what was said in the EPU have become a bit of a blur. At home now in the late afternoon, everything is going wrong again. K is in agony, bleeding more and more and we need to get her back into hospital.

Test results from the morning were consulted: her HCG went up again. They found her a bed and put her on a drip for fluids. At one point she overhears the case conference going on in the hallway. Keyhole surgery on her fallopian tubes is mooted and the radiographer’s theory about the neck of the womb ruled out. One thing is certain, after three weeks and two days, she is to have the D and C, the dilatation and curettage procedure that should draw the physiological experience – the miscarriage itself – to a close.

The D and C fulfils its function, K stays in until Tuesday, when a significant fall in the levels of HCG means she can come home, now completely exhausted and sore from the operation, on 9-11, the 11 September 2001.

The global mourning in the wake of the attack on the World Trade Centre suits the mood in the house well. K dozes on the sofa for weeks as funeral follows memorial on daytime television. I am back at work, but K finds it physically difficult to leave the house after her operation and often spends days without seeing a soul. Occasional promises to come around are made on hurried answer phone messages, but they never turn up. They just don't want to talk about it.

She only ever got one get-well card, which makes me angry to this day. How much effort or involvement does it take to write ‘thinking of you’ on a blank card? How about some other non-specific greeting which would just let her know she isn’t – we aren’t– alone? Forget it.

I’ve since realised that the guiding intent is keeping a respectful distance, but it pays no respect to maintain the taboo. We are, at last, familiar with the idea of acknowledging death and the importance of the processes of grief and bereavement. We know we cannot say exactly the right thing to someone who is suffering, but at the same time we know we must communicate so that our discomfort doesn’t trample on their pain or loss. A sudden void can be filled with reassurance, a silence with softly spoken words.

Yet, when it comes to miscarriage – a potent mix of grief and birth and life and death – we are a long way from coming to terms with it. What hope for a grieving couple when the silence of society won’t acknowledge their loss?

About the Creator

Ian Vince

Erstwhile non-fiction author, ghost & freelance writer for others, finally submitting work that floats my own boat, does my own thing. I'll deal with it if you can.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.