My Father's House

My Father's House

I am standing in the house my father built.

The rooms are cold, as they always were. The myth of California is that it’s always warm. Instead, the damp gets inside of you until your skin crawls. The heat was never turned on in my father’s house.

I am wearing a sweater Katy gave me last Christmas. Now Katy and my father are gone. Katy, of course, is still alive, living about an hour outside of Seattle. She has a new husband, several horses (his) and a pottery studio (hers). I hope she is happy, happier than she was with me. The day she moved out, she told me that I was a feckless dreamer. She also implied that I was cold and unresponsive as a lover. The truth is we had simply fallen out of love.

My father passed away six months ago. We had not seen each other for ten years. We had fallen out of love long before that. I remember loving him very much as a young child. All boys form a filial bond with their fathers, and I was no different.

He could be very doting. A favorite game we played was peek-a-boo. But my father thought the name “peek-a-boo” was too childish, so he called it “Do you see me now?” He would cover his face with his hands while I looked on, hypnotized by his Goliath size. Behind his wall of fingers he would say,”Do you see me now?” I would stare and wonder. Then he would say it again, still behind staid hands. “Do you see me now?” His hands didn’t move, and I grew frustrated. What was this secret? Then, with a flourish, he would part his hands, revealing a radiant happy face. “Do you see me now?“ he chimed. I would giggle and squeak at the revelation, no matter how many times we played it.

When I was three, I would watch my father shaving. He bought me a toy safety razor that came with cardboard blades. Every morning, he would shave and I would shave by his side. One day, when my father was down stairs watching a football game, I decided to try out the real thing. I climbed up to the medicine cabinet and took out my father’s safety razor. It was heavier than my imitation one, and cooler to the touch. I looked in the mirror and drew the shaver across my face. The blade dug into my skin.

I dropped the razor and began to wail. Blood was running down my face, dripping onto my Snoopy T-shirt. I shrieked. My father flew into the bathroom, assessing the situation in a moment. He grabbed a wash cloth, dousing it with cold water, then knelt down in front of me and dabbed my bleeding cheek, finally pressing the cloth firmly to my face. I was still unconsolable. It wasn’t so much the pain; it was a feeling of betrayal. My father’s razor had injured me, causing me to bleed, causing me dishonor. My father didn’t approve of crying.

“Be a man,” he told me, still pressing the cold cloth against my cut. “It’s not that bad.” His face looked stern. I think he had been scared by the incident too, but he was always about teaching me his number one lesson, “Be a man.”

I still bear the scar of that day, though time and age have worn the facial blemish down to a white wisp, only visible when I point it out to people. Katy loved that scar, said she thought it was sexy. Back when we were in love, she used to kiss that spot most tenderly.

My mother highly disapproved of my father’s attitude, telling him that real men were sensitive and caring. “We’re not raising a soldier,” she would implore him, “we’re raising a child.” But he would not be swayed. His father had taught him to be a man, and his father before him.

My father had wanted to be an artist. He showed real promise as a young man, excelling in his art classes all the way through his first year of college. But his father didn’t approve, saying that art was for dreamers and miscreants, and that no son of his would ever follow that path. So my father began to study architecture, but had no great aptitude in that direction. His talent leaned to interpretation, not the exacting demands of buildings and schematics. Finally, to ameliorate his father, he became an accountant. Those are the choices that make a man hard, even bitter as the years wear on. But to be a man, one must absorb those feelings. “Suck it up,” my father used to say to me on many occasions when I looked like tears might bell welling just behind my eyes.

To this day, I cannot cry.

Now, standing in the living room of my father’s house, the memories creep in like the fog of a California dawn. I am here to take one last look around, to see if there is anything I may want to keep before the house is turned over to its new owners. I sold the house in order to cover various expenses and debts left behind by my father, mostly having to do with the long illness which finally ended his life. After escrow and fees, along with funeral costs and lawyers bills, I was left with twenty thousand dollars, give or take. It was adequate, and more than I expected.

Actually, what I had expected was nothing.

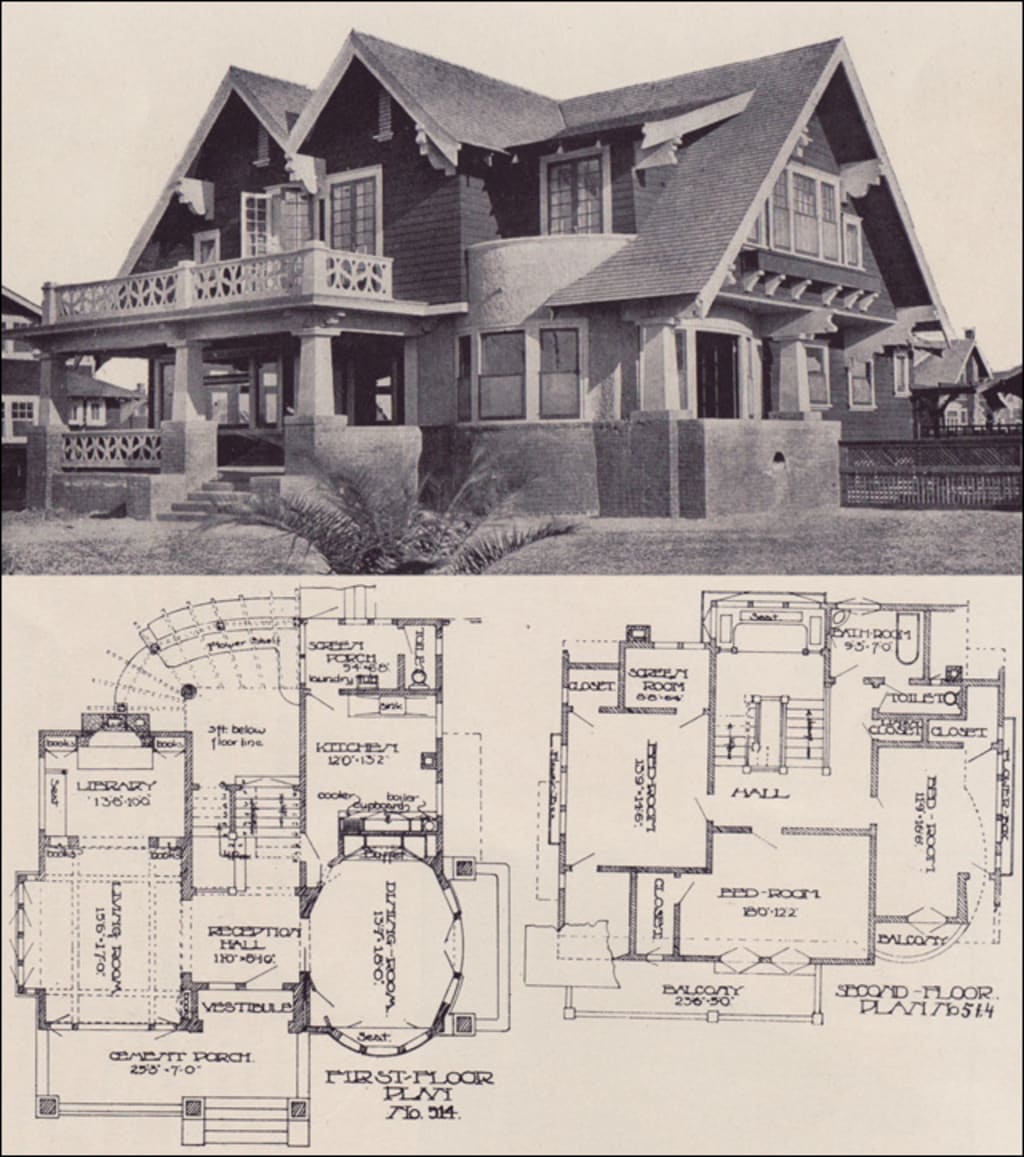

My father built his house when I was twelve. He decided to dust off his old architecture training and design the building himself. Years later, my mother told me how painful it had been meeting with the construction firm. They had many celebrity clients and were used to humoring their various demands, but few of those came in with finished blueprints. The ones my father brought were obviously the work of an amateur. My mother watched as my father laid out his plans, watched the gathered designers and engineers glance at one another, smirking and winking and clearing their throats. To hear her tell it, they nearly laughed him out of the office.

My father sucked it up of course, but he was not stupid. He knew he had been humiliated. After that day, he turned irritable and increasingly moody. The house was built, with as many of my father’s original specs as possible, but there was no joy in it. We moved in, going through the motions of setting up a new house. My father had designed a room at the rear of the ground floor which he called his library. There was an unstated rule that we were to keep out of there. My father would spend more and more hours in that room alone.

Shortly after we moved in, my father stopped sleeping with my mother. He moved into a spare room on the second floor. I knew what was happening, but kept it to myself. My father for the most part kept to himself. My mother, finally, had had enough. On my fourteenth birthday, while my father was at work, she told me to pack a bag. We left in a taxi, driving directly to LAX. We boarded a plane to New York where my mother’s family lived.

We never returned.

I missed my father, of course, and would speak to him on the phone once a week. He would ask me about my school work, if I was playing any sports, if I had friends. My answers were perfunctory; pretty good, some, a few. He never spoke about my mother. Our conversations turned more and more halting, more disjointed, with painful pauses that lapsed into melancholy. Eventually, our calls dwindled to one a month, then on holidays only. By the time I was entering college, we only spoke on my birthday.

By that time, I had turned to music, playing the guitar to ward off the blues, and had begun writing songs. I wrote only a few at first, but I got good enough to front my own band, playing various clubs up and down the east coast. My father and I had rarely quarreled, but when I told him about my musical aspirations, he exploded.

“What makes you think you can be a musician?” he asked. “That’s no way for a man to live.”

I pointed out to him that many men my age were making handy livings in the music world, but he would have none of it. And I would no longer be lectured on how to be a man. After that, there were no calls at all.

Now, standing alone in my father’s house, that silence reverberates like water droplets in an endless cave. There is little here that I want. I take a turn toward the library. Where the shadows dwell.

Outside, a hazy drizzle patters against the rooftop. I walk to the library door, turning the cold brass handle, walking inside.

There is a desk facing the door. On it are piled stacks of Moleskine notebooks, all black. My father used to carry around a Moleskine, jotting briefly into it at moments. I asked him about it one time. He told me that a man has thoughts best kept to himself. I didn’t ask again.

A large olive green blotter covers the front of the desk. On it is a single Moleskine notebook, black, banded, shiny. On the notebook is a yellow Post-It note. It reads,”For my Son.”

I remove the band. The first page is blank, white, empty. I turn the page.

There is a drawing of my father, a self portrait of a young man, steely eyed, self assured, proud.The drawing is impeccable, tiny pen strokes creating a near photo-realistic image.

Turn the page.

A picture of my mother, also still young. A girl smiling, a smile that asks to be held.

Turn the page.

A man of stern visage, my father’s father, dressed in a business suit, all tweed and silk brocade, light glinting off a Windsor knot neatly tied.

Turn the page.

A baby in my mother’s arms. He is looking up to her with all expectation, all hope, all hunger.

Turn the page.

Me as a young boy, dressed in a slightly-too-large baseball uniform, cap draped over one eye, smiling.

Turn the page.

A field of flowers, copious robust blooms, back as far as the eye can see, and pushing all the way up to the front, where the blooms are of such detail, you can almost smell their bouquet.

Turn the page.

Sketch of a blueprint, a house in the planning stages.

Turn the page.

Close-up of a liquor bottle, Black and White Scotch. Two Scottie dogs printed on the label, one black and one white. The bottle is half empty.

Turn the page.

My room, the one I left behind as a young man of fourteen, disheveled, drawers newly emptied standing open. A Star Wars poster, torn, hanging over the bed.

Turn the page.

An old man sitting in the park, couched on a bench, looking disconnected and alone.

Turn the page.

I am taken aback. It is a drawing of Katy in her wedding trousseau. She looks as radiant as I remember, bold and amorous. As far as I knew, my father had not attended my wedding.

Turn the page.

Another picture of me, this time singing into a microphone, lit from above by a beam of cross-hatched light, my guitar slung by my side.

Turn the page.

A single line, written in my father’s pristine script. “Do you see me now?”

I close the book. Outside, the rain has stopped. Only the sound of drips and drops falling from the eaves of my father’s house. Mingled with the sound of my own breathing.

And crying.

About the Creator

Louis Chalif

Born NYC. Now Lives in Los Angeles

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.