ASD Snapshot: Alias Jungle Boy

~ A moment in time that defines: identity and coping

"Is this what I think it is?" Erik's eyes shine; dimples emerge, playful.

"That depends," I muse, ". . . what you think it is."

"I think you know what I think," he says, smile swelling. This is better than Christmas.

We have stumbled upon outgrown treasure, uncovered a former Erik, and there it rests, silky and green and vulnerable on his bed. We both gaze at it, remembering.

"It's Jungle Boy," he whispers, as though face to face with celebrity.

"It's your former skin, Erik."

"Yes," he breathes, leaning in and stroking the flimsy fabric. "It's the me that used to be me. . . It's so small. Was I that small?"

It's true: the costume, a shimmery Peter Pan suit, emerald green, jagged, lustrous and limp, is petit. It could be bunched up in Erik's twenty-two-year-old fist. At six-foot-one, Erik would be hard-pressed to pull the pant portion up over one leg. The waistline is impish and sweet. Was he really that small?

He cocks his head. What did I see in this costume? And why am I so happy to see it now?

I know why, Erik. Jungle Boy was the way you defined yourself for a chunk of your childhood. It was who you became after school each day to cope with the boy you needed to be at school. Jungle Boy was your self-regulation, your life ring. It was your safe self.

"Where was it. . . all these years?" he stammers, processing.

"In the basement. . . with the other dress-up clothes. I was down there a minute ago, searching through the storage bins. And there it was, curled up in a tote. I was so excited when I found it. . . like running into an old friend, but better. Like time travel, being handed young Erik. Like rewinding the clock and stepping back."

~

Our after-school routine was predictable back then: We would come home from our school pickups, tumble out of the van, artwork, lunch kits and backpacks, and disperse once inside the house. Scott and Heather would regale me with snippets from their school day and pull papers out of their backpacks—forms to be signed and such—and plunk it all on the desk. Erik would be nowhere in sight.

Moments later I would spy the headgear: a felt replica of Peter Pan’s pointy green hat. I knew to follow.

“Welcome to my jungle home!” a joyful falsetto would squawk, clicking on a sound effects device. Songbirds and a burbling stream floated us south of the equator. The effect was soothing, immersive.

“What would you like to do today? Fish or swim?” In this, our curious blonde boy blurred to Jungle Boy, calm and content in his leafy lair.

This was the way it was most days after school: a disappearance, an identity swap and a reemergence, green and gregarious.

The costume was a change agent. Erik would slip it on, cool and silky-soft, like stepping into a welcoming skin.

The transformation was astonishing: from pinched and panicked, to joyous and jovial.

I have read that children with autism often adopt a character, live through it, speak through it, and become it. Sometimes it is a beloved Disney character; sometimes it is an object or person which represents a special interest (as a preschooler, Erik had become Erik Whale), and sometimes it is fabricated, an invention of a mind that whirs without boundaries. In Erik's case, Jungle Boy was an extension of his bedroom.

Observing that nature soothed the boy, we tacked up leafy wallpaper to create a feature wall. He shared a loft bed with plush monkeys, brightly coloured tree frogs and one congenial leopard. A large lime leaf canopied the bed. Spotted and striped carpets formed the jungle floor; a faux zebra-skin carpet was tacked to the wall.

The room was a calming mishmash of India and Africa, a jungle and savannah meld, and the effect was tranquil, exotic and removed. It was an escape. Jungle sound effects and dimmed lighting invited Jungle Boy to lose himself in his bedroom sanctuary. In the space beneath the loft bed, a small tent filled with pillows offered a sensory retreat.

But it was the costume that was the clincher: Jungle Boy allowed Erik to tame the confusing, bustling school day and become something serene—no strings, no boundaries, no confusing rules.

Fictitious characters don't make social blunders. You can’t be wrong incognito.

Jungle Boy operated according to his jungle culture, and while Erik was green, he was immune to the unspoken social rules which confused, plagued and confounded him. The costume was Erik's buffer. In costume, he could simply be.

Leave him in his emerald oasis, and Erik was the best version of himself. Remove the pointy hat and shiny jade costume, take him outside and expect him to integrate with neighbourhood children? Things became tricky and turbulent.

Defaulting to a fascination is something we all do: we watch movies; we lose ourselves in novels, we travel to shake up the routine. Escapism is a temporary pass, permission to dodge what we need to do—or be. We live, for a time, through others. It’s nothing new.

Jungle Boy, Erik tells me, was his childhood armour. And for a young boy struggling to puzzle out his social world, it was something more: a childhood superhero.

____________________________________________________

Points to Ponder: How much effort and energy does it take to negotiate a school day? Any social outing? A lot. Layer in autism, and imagine life through our children’s lens. Allowing Erik to become Jungle Boy felt like a small concession, the least I could do. Sometimes I felt I ought to be doing more, trying harder to integrate him with the neighbourhood children. But then I thought, no, take a line from the Beetles, and “let it be.” Let him be. Give him time to come down from a day that must have been incredibly hard to navigate. Alias, Jungle Boy.

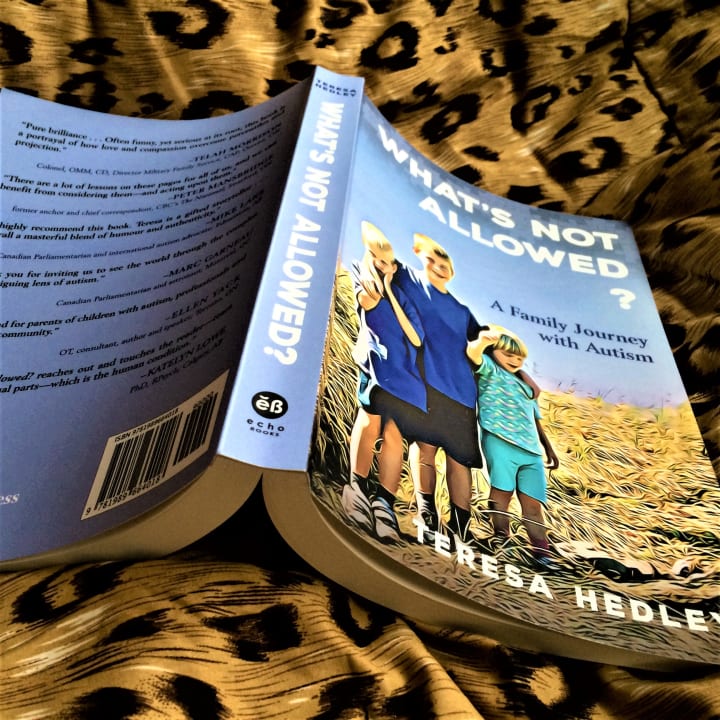

Teresa Hedley is the author of What’s Not Allowed? A Family Journey with Autism (Wintertickle Press, 2020), a memoir which offers an uplifting approach to mining the best version of each of us, autism or not. Teresa is also an educator and a curriculum designer. Teaching stints in Canada, Japan, Greece, Spain and Germany have shaped her perspective and inform her writing. Teresa and son Erik co-wrote a twenty-article series for Autism Matters magazine, “I Have Autism and I Need Your Help.” Additionally, Teresa worked directly with families and school boards in Ottawa as an autism consultant and advocate. She and her family live and play on Vancouver Island, Canada.

"Teresa Hedley’s honest sharing reaches in and alters the hearts and minds of the reader to look beyond a label into the possibilities that emerge from the willingness to align with what is."

–KIM BARTHEL , occupational therapist, international speaker, consultant, author; Victoria, BC, Canada

About the Creator

Teresa Hedley

Greetings from the beach... where you'll find me exploring, reading, writing, hiking and kayaking with our local seals. I'm excited to share my stories with you via What's Not Allowed? A Family Journey With Autism. Now on Amazon + Chapters

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.