ASD Snapshot: Can I Go?

~ A moment in time that defines: growth

In Transition

We are still learning to drive.

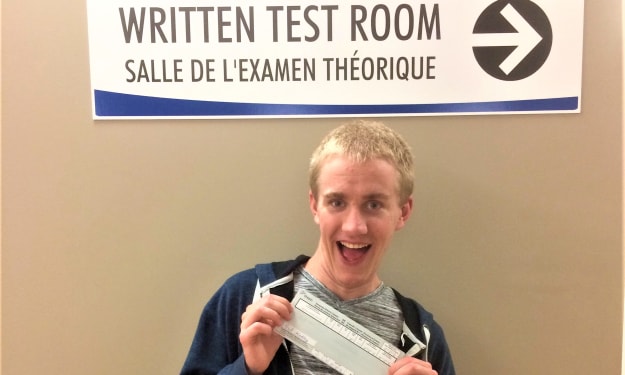

Months after passing the Ontario written test (six swings at the bat), we move to British Columbia: another province, another test. No biggie, I tell myself. Erik can write the BC learner's test during the last week of August, the week before college orientation begins.

We study the BC book and download the app, but we delay the test taking. Too much is going on around us. We are in transition, after all. “Wait a month,” I say to Erik. We are both relieved.

September. October. One month becomes three.

November brings stormy seas and growing anxiety. We—he, the lead, and I, the sidekick-note-taker—are ticking off prerequisite courses for further college, and between Food Safety, CPR and WHMIS (workplace safety), there is not much time or inclination to squeeze in driver’s education.

But Erik is game to take a shot. He tries the written test and fails. He cannot believe it: this is number seven.

In December, autism comes calling. Erik is feeling so much pressure to achieve in college, in a new supervised work placement, in his new life, and with the driving project, that he folds, stops communicating with me and buries the driver’s handbook in his sock drawer.

What have I done? I am rattled and remorseful. But I thought we would have this nailed by now, that he would be driving me all over this fabulous ocean playground. Instead, he is being drawn down—or perhaps buoyed—by autism. He is rocking and pacing and whispering. He is not studying and he is not driving.

Messy reality. It is then I say to him, simply,

"I'm going to let you take the lead on this. You'll know when you feel ready. Study and let me know.”

I offer space, prepared to let it slide for a while. And then one day in January, "Let's go in on Wednesday. I feel ready." So we do. Eight.

But this eight, like number six, produces a win. "Well? Did you pass?" I say as he approaches me in the waiting area.

"Dunno, but the computer didn't shut down on me this time. It looks more hopeful."

We go to a desk and the lady is beaming. "Eighty-four per cent, Erik! Congratulations!"

She seems to know that this is a big deal; she's very happy for him. People react like this around Erik. They pull for him, the humble blonde boy with the lopsided grin.

And so he takes the wheel again on this coast, creating themes and even driving with the radio on. We are coming home one day, and I glance over at his profile. Just like his father's. And peeking at this outline again, I can see it is smiling. Beyond him, the island mountain range, turning purplish in the fading light.

"This is great!" he says, eyes never leaving the road. "I'm driving you! The scenery is nice. The music is good. I feel in control. And what I really like is..."

He pauses, and in my mind I fill in the blank: the sense of freedom.

But no, not that.

"What I really like is that from the driver's seat, I control all of the windows and doors! I really like that aspect of driving."

In the Driver’s Seat

The "L" designation goes on for a very long time, lurches and regresses, and slowly, like everything else, evolves. It's Erik's way.

"Can I go?"

He used to say it constantly, at every intersection, at every four-way stop, and for my own safety—and for the clarity of the others drivers—I would answer him right away. "Yes" or "Hold up!" but rarely what I should have said, "What do you think?”

I said that once, but it was at a critical moment, at a time he was turning left in front of oncoming traffic. He didn't see it as prime time for reflection and analysis. He snapped at me instead. "Well I need to know. So tell me!"

So of course I did. I was in the passenger seat and wished to remain there. But over time, I stopped replying, especially when there was no urgency.

One day I turned to him,

"The objective is for you to drive independently. Without me or somebody else to give you the green light or to shout "stop!" You need to be able to figure this out. So stop asking me."

Because this came while we were parked and gazing out over the calming ocean, he agreed. He was in charge, in the driver's seat, and that meant body and mind in sync—without helpers.

Today we passed through a busy intersection where he needed to scan, merge and then scan again, quickly change lanes and then make a left turn in front of oncoming traffic: a four-in-one doozie. Like a back dive off the high board with a twist and a high degree of difficulty, he did it seamlessly, voicelessly. And I realized that I was occupied and didn't notice it was through—that we were through the intersection—till I heard him exhale. My own breath hadn't even registered. Out to lunch or on to something? I couldn't decide.

And then we both marvelled. "I did it!". . ."You did it!"

It didn't seem to be a big deal anymore.

"I've noticed that in driving and in life, the more I pull back, the better you do. Trim the mother limb, let the sapling get some light and water, and just watch it grow."

Erik's growth depends upon my growth.

"I shrink, you grow," I added, as a way of summing up, and we both immediately liked it.

"Our new tagline!" suggested Erik, and so it is.

I shrink, you grow. And on we go.

____________________________________________________

Points to Ponder: How often is failure to achieve simply failure to meet expectation—our own and those of others around us? Nelson Mandela once declared, “I never lose. I either win or learn.” Reframing failure as a point of illumination—and learning—changes everything. Once we began to reframe “failures”—swimming lessons, driving tests and other standard measures where Erik fell short—as “practice rounds,” everything changed. The focus shifted from letdown to learning, and that changed the way Erik thought about himself. Mindset matters.

Teresa Hedley is the author of What’s Not Allowed? A Family Journey with Autism (Wintertickle Press, 2020), a memoir which offers an uplifting approach to mining the best version of each of us, autism or not. Teresa is also an educator and a curriculum designer. Teaching stints in Canada, Japan, Greece, Spain and Germany have shaped her perspective and inform her writing. Teresa and son Erik co-wrote a twenty-article series for Autism Matters magazine, “I Have Autism and I Need Your Help.” Additionally, Teresa worked directly with families and school boards in Ottawa as an autism consultant and advocate. She and her family live and play on Vancouver Island.

"Relatable, honest and eloquently shared, What’s Not Allowed? is a journey of joy, of moving forward, a testament to the value of staying curious, positive and patient."

–SARAH FORD HOLLIDAY , MS, CCC/SLP; Lewisburg, West Virginia, USA

About the Creator

Teresa Hedley

Greetings from the beach... where you'll find me exploring, reading, writing, hiking and kayaking with our local seals. I'm excited to share my stories with you via What's Not Allowed? A Family Journey With Autism. Now on Amazon + Chapters

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.