The Very Model of A Modern Major Musical

The History and Evolution of "The Pirates of Penzance"

CHAPTER 1: An Oratorical Overture

Picture if you will. A musical theatre student receives the announcement of their school's upcoming Gilbert & Sullivan production. If you were this hypothetical student, what would be your immediate assumption of which show it would be, from their collection of works? If the school's theatre department was headed by the choir director, then there's a good chance it may be HMS Pinafore. Or perhaps The Mikado, if the department head is a cultrally, out of touch, bigot. Yet, the most likely show, under any other circumstance, would be The Pirates of Penzance. Even if you've never seen the show before, there's a strong chance that you know a decent deal about it. Besides the show having pirates in it, it's a show that incorporates a lot of physical comedy, as well as a script that seldom takes itself seriously. Furthermore, you may know the show's most famous song. I am the Very Model of a Modern Major General.

A tune that has achieved fame for its use of rhythmic repetition and intelligent lyrics, the incredibly fast pacing of the score, and how it's been parodied by almost anybody and everybody; from Veggie Tales, to Phineas & Ferb, to Family Guy, to Despicable Me 3, to Animaniacs, to various YouTubers.

However, I digress. Going back to the hypothetical scenario in the beginning, I must ask you a question. Why did you almost immediately jump to the conclusion of the show being The Pirates of Penzance? Gilbert & Sullivan wrote far more than just that one work. In total, they created fourteen operettas throughout the course of their careers. To this very day, there are a plethora of theatrical companies solely dedicated to keeping the works and traditions of Gilbert & Sullivan alive and on stage, ever since their first collaboration, in 1871. That's 153 years as of the writing of this piece, in 2024. Many experts in the field of opera and operetta will sing the praises of their work, due to their lasting power and cultural relevance, as well as the writing (on the same plane that contemporary theatre critics commend the works of Ahrens & Flaherty, Stephen Schwartz, or Lin Manuel Miranda). So, with all that in mind, why is it that the majority of companies will only produce The Pirates of Penzance? Why that one show, out of the rest of their Victorian era canon? What about the show has changed since its 1879 premiere?

Well, surprisingly, the high energy, loud belting, and physically demanding version of the musical we know of, today, is anything but what a Gilbert & Sullivan operetta is supposed to be. One could easily jump to the conclusion of how it slowly evolved from the old school methods of the "grand theatre" as new standards of Broadway and West End musicals revitalized a classic over the course of a century. Unfortunatley, that was not the case for The Pirates of Penzance. Rather, it was only one production, in 1980, which dared to completely destroy the archaic rules of putting on a Gilbert & Sullivan show, and replace them with new ones; eviscerating the old fashioned libretto, and instill elements of contemporary pop rock in its place. This one production would take an high culture operetta, and transform it into a low culture musical comedy.

This is the story of The Pirates of Penzance's transition from a British operetta to an American musical.

CHAPTER 2: From Victorian Beginnings

Turn back the clock to the year 1878. Librettist W. S. Gilbert and composer Arthur Sullivan are in the process of creating their newest theatrical work, called HMS Pinafore. The operetta serves as a humorous work of satire. Observing the class system of the British Royal Navy, in a way that promotes unqualified individuals to power and prestige, through nepotism; as well as the treatment of marriage as a short term business deal, rather than a lifelong romantic commitment.

This would be their fourth collaboration as a creative duo, as well as their second collaboration with the Opera Comique theater, with their business partner, Richard D'Oyly Carte. Mr. Carte was also one of the key producers for many of Gilbert & Sullivan's previous productions; including Trial by Jury and The Sorcerer. Following the incredibly massive success of HMS Pinafore, Mr. Carte realized that the work of these two gentlemen fit perfectly with his artistic agenda of promoting family friendly, and aesthetically British-styled operetta; in order to compete against the much more lude, raunchy, and French inspired burlesque shows that were occupying London's theatre district. Furthermore, with a financial plan of wanting a much more even split of the profits between Gilbert, Sullivan, and Carte, the three parted ways with the Opera Comique, and eventually founded their own independent company, known as the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company.

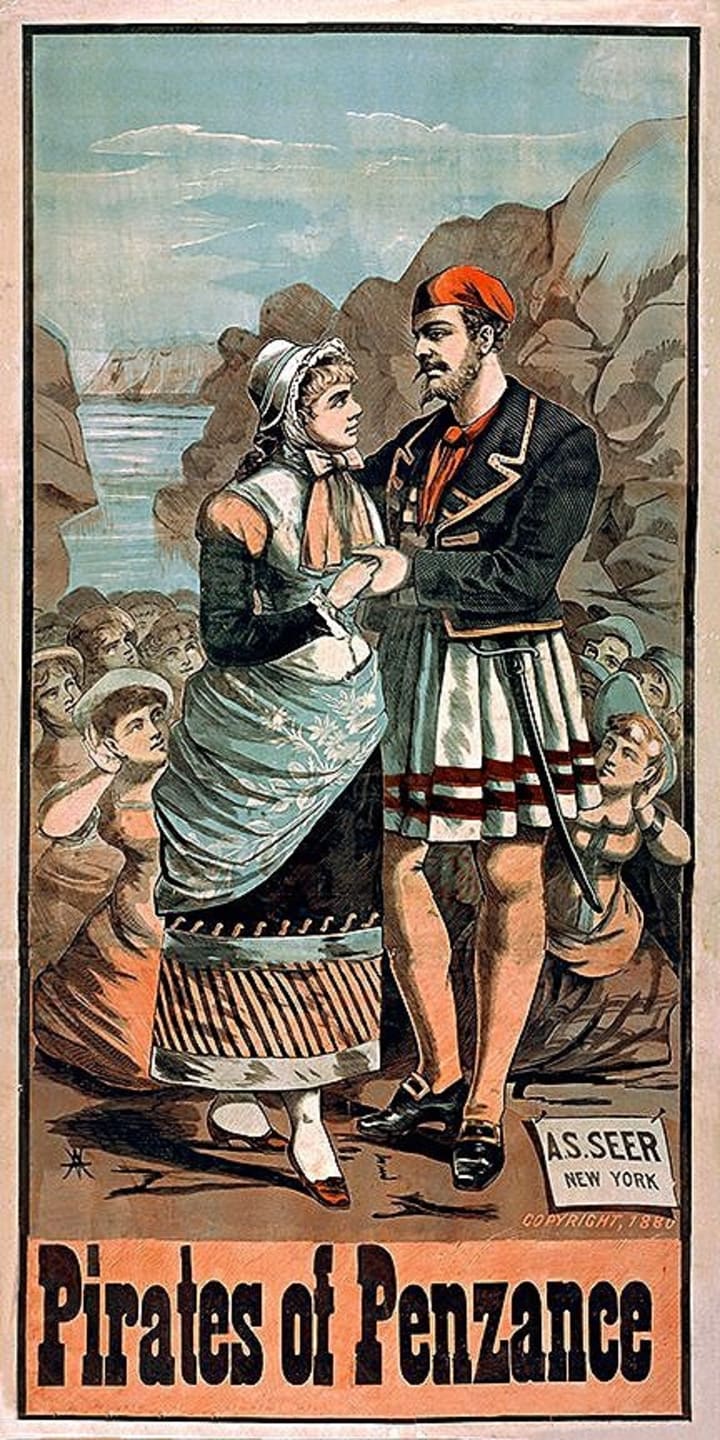

This would allow the trio to assume full, legal, and financial control over their productions. Emphasis on "legal" control, regarding their productions being put on within the United Kingdom. The theatre markets overseas were a different story. Copywright law in the United States had no provisions (at the time) for international artists, and American theaters had free range to put on works, without having to pay the appropriate owners, that were residing across the pond. In order to secure their copywright, and following their discovery of these unauthorized productions, The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company formally staged HMS Pinafore in New York. Yet, this would lead the trio to be far more cautious and protective of their future works; preventing any piracy (pun intended) from American companies. Mr. Carte devised a plan to have Gilbert & Sullivan's next show have an official premiere, in New York, on December 31, 1879, and follow it up with a London premiere on April 3, 1880. That show being The Pirates of Penzance; becoming an almost instant hit, and being added to the revolving repertoire of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company in 1893; remaining in repertoire until the company closed down in 1982.

The Pirates of Penzance; or, The Slave of Duty, follows the signature mold of Gilbert & Sullivan's other operettas. Serving as a comic reflection of the British social hierarchy, with a ridiculous circumstance being resolved by the greatest means of common sense. The story surrounds Frederic, a sailor and mistakenly-made apprentice in a band of pirates. He remains loyal to the crew and their pirate king, until his 21st birthday. After he formally leaves them, he arrives in Penzance, England. There, he discovers a group of young ladies who are all the daughters of a "modern Major General", and falls in love with the most beautiful of them all; Mabel. From then on, hijinks ensue; including the pirates' vow to never pillage or plunder from any orphans, a contract loophole regarding Frederic's date of birth on February 29th (making him believe he's actually five years old, instead of 21), as well as a very cowardly and ill-equipped police force.

Following a clash between the pirates and the constables, the show concludes with Major General Stanley becoming impressed by the discovery of how the pirates are all "noblemen who have all gone wrong", forgiving them, and allowing Frederic to marry Mabel. The show's libretto also contains many instances of more subliminal humor within the main story. However, modern audiences often find it too difficult to understand. For example, in the opening song number, the pirates drink sherry (instead of grog or rum); a style of alcohol most commonly consumed by Victorian high society.

CHORUS OF PIRATES: Pour, oh pour the pirate sherry, fill, oh fill the pirate glass! And, to make us more than merry, let the pirate bumper pass!

Another example can also be found within the lyrics of I am the Very Model of a Modern Major General. Near the end of the song, he confesses that his only flaw is his lack of any real military skill. Something that a general should fundamentally have.

MAJOR GENERAL: For my military knowledge, though I'm plucky and adventury, has only been brought down to the beginning of the century. But still, in matters vegetable, animal, and mineral, I am the very model of a modern Major General.

Even the show's title is meant to be a joke. Penzance is a seaside resort community at the very southwest tip of England. The last place in the world that would ever serve as a haven for pirates. In more contemporary times, the joke would be on par with calling the show The Pirates of Lake Tahoe. The point being, that even in its own time, this was a show never intended to be taken seriously. Alongside the rest of Gilbert & Sullivan's work, it was deemed a comical "operetta". The first "musical" as we have come to define it, today, wouldn't come into being until 1927's Showboat (with some experts debating that the first real musical was actually The Black Crook in 1866; but I digress). The vocal styles between operettas and musicals can more often than not be as contrasting as oil and water.

Furthermore, for those of you reading this, who may have actually performed in an operetta, you may know how an operetta's writing can be very different than how a musical is written down. In musicals, a licensed production comes with a dialogue book, with italicized directions serving as a hypothetical guide as to how the scenes could be staged, and a separate musical score. In operetta, that is often not the case. The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company used to mandate entire pages of set design and stage directions, alongside the libretto and score, to mandatorily control how each scene should look and how each song should be choreographed. In their eyes, the works were to be frozen in history, like an artifact buried in a time capsule and kept in its antique-like condition whenever discovered by future generations.

As time went on, though, Broadway musicals would begin to become the much more dominant format of live theatre for those future generations following the Victorians. Operettas were slowly and surely fading away from the cultural zietgeist. Prior to the D'Oly Carte Opera Company's closure, they did manage to keep the legacy of Gilbert & Sullivan alive by recording all fourteen of their shows made between 1871 and 1896, before the librettos and scores fell into the public domain, in 1961. Yet, the new lease on theatrical life for The Pirates of Penzance wouldn't necessarily come from the show's public domain status. It actually came from (ironically) a political big wig's decision to cut funding for the arts.

CHAPTER 3: Modern Times Call for Modern Measures

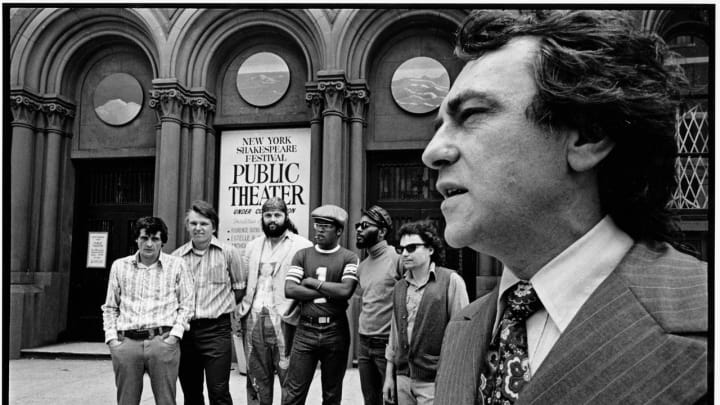

In 1980, New York City was suffering from severe economic and political troubles unlike any its residents had experienced prior. With the decline of heavy industry, rising unemployment, skyrocketing crime rates, major businesses moving away to other parts of the country, and the looming risk of the city filing for bankruptcy, Mayor Ed Koch responded by making several cuts to the city's budget; with his biggest cut being a severe reduction of funds that was designated to the Office of Cultural Affairs, as well as the removal of all financial backing for the Public Theatre's New York Shakespeare Festival (which operates the free to attend, Shakespeare in the Park, every summer). Following this monetary setback, Public Theatre producer Joseph Papp would personally respond by announcing his plans to cancel the summer production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, at the outdoor Delacorte Theater, that year. While on a cab ride with director Wilford Leach, Papp disclosed his plan to stick it to Koch, by having him produce Gilbert & Sullivan's The Mikado, in substitution for Shakespeare in the Park. He instructed Leach to find the soundtrack and listen to it. This plan would later be changed to putting on The Pirates of Penzance, after Leach failed to find a copy of The Mikado at any of his neighboring record stores, and wound up purchasing The Pirates of Penzance instead; allegedly because he thought the album art looked cooler than the other Gilbert & Sullivan albums that were available.

Only after listening to half the songs on the B-Side of the record, Leach called composer Bill Elliot over the phone, and announced that The Pirates of Penzance would be the Delacorte's summer show. Although, neither Leach, nor Papp wanted to put on the show according to the rules of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company. Given that the show was already in the public domain, for well over a decade, they didn't need to contact the company. What they did need to do, was find a way to make the show more appealing to audiences that had long since left the works of operetta in the past. That goal would ultimately require them to reevaluate the nature and societal role of the show; asking themselves how audiences saw it not as a classic, but as a bold, new work. Still, this idea of creating a new vision for a classical stage work was very divisive among theatre goers and critics. As early as 1970, director Peter Brook defied convention by putting on A Midsummer Night's Dream at the Royal Shakespeare Company; using a completely barren white set, as well as rudimentary costumes and props (requiring the viewer to rely on their sense of imagination over the dependency of realism).

It was also a rule of thumb in the world of opera, that the orchestra conductor wields control of the show. This was challenged in 1976, when the director of a production of Richard Wagner's The Ring Cycle discarded all previous traditions, in terms of the scenery, and set the story in a dark and exploitive factory, during the Industrial Revolution; with the Rhinemaidens are depicted as prostitutes. This production almost sparked a riot by the audience.

Yet, Leach knew these age old rules needed to adjusted or outright tossed aside if he and Joseph Papp's newest endeavor at the Delacorte was to be successful. In his mind's eye, if Gilbert & Sullivan were the pop music of the 1870's, than their version needed to sound like the pop music of the 1980's. That mindset brought about the addition of synthesizer into a much more reduced orchestration. Furthermore, the casting choices for the two leads, would be aimed towards singers who could act, over actors who could sing. This would lead to the hiring of Linda Ronstadt for the role of Mabel & teen pop idol Rex Smith as Frederic. Who else was cast to fill up these lead and supporting roles?

- George Rose as Major General Stanley.

- Patricia Routledge as the pirate maid, Ruth.

- Tony Azito as the Sergeant of Police.

- Kevin Kline, as the Pirate King.

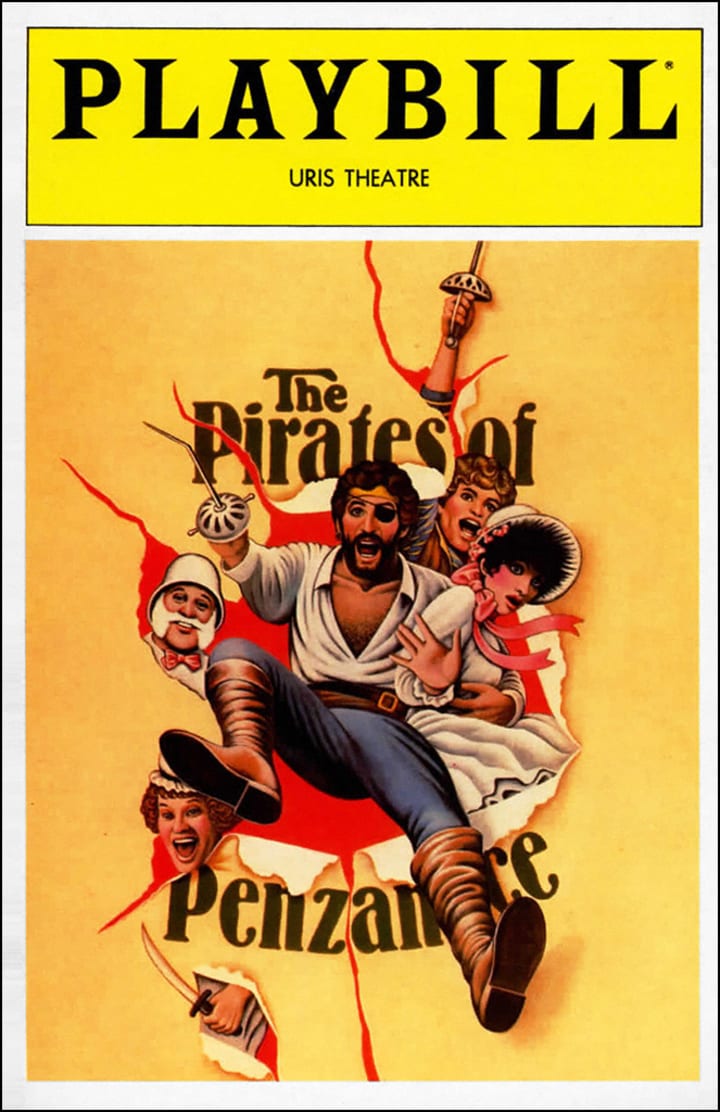

Staging the show in an outdoor venue, like the Delacorte, brought the action of the story closer to the audience than any prior production ever had. The pirates and daughters would also break the fourth wall by running through the audince isles, while Kevin Kline would improvise a sword fight with the conductor and his baton. This much more tongue and cheek way of envisioning the show, would be met by almost universial praise by audiences, night after night. Which would eventually cause the show to be transferred to the Uris Theatre, on Broadway, in 1981; running for 23 months, receiving a total of seven Tony nominations, and winning three (Joseph Papp for Best Revival, Kevin Kline for Best Actor, and Wilford Leach for Best Director).

Come 1983, Joseph Papp & Wilford Leach would be brought on by Universal Pictures to direct a film adaptation of The Pirates of Penzance; bringing back almost the entire original cast from the stage show, except for Patricia Routledge (who would be replaced by Angela Lansbury). Compared to Papp's stage version, the only significant differences is the inclusion of more humor in the visuals and improv.

There was also another film adaptation, made about a year prior, called The Pirate Movie; but is by no means as good as what Papp and Leach created; coming off as a weak and cash hungry attempt to profit off of the success of the musical, with bad writing, and outdated pop culture references on par with the string of abysmal Friedberg and Seltzer parody movies (Scary Movie, Date Movie, Epic Movie, Disaster Movie, etc.)

CHAPTER 4: Where We Stand, Today

As the years have gone by, it has now become hard to overstate the impact of this one New York production, and how it has influenced almost every production that has come in its wake.

- The Pirate King looking more like Douglas Fairbanks, Errol Flynn, or Johnny Depp, than Captain Kidd or Blackbeard.

- The key change and encore for the song With Catlike Tread.

- The hilariously increasing pace of I am the Very Model of a Modern Major General from the beginning to end of the song, while wearing a pith helmet and umbrella; rather than a bicorn and sword.

- Any production that uses a poster with the background being torn open by the main characters.

- The concept of the show being simultaneously improvised by the actors, in the course of the moment, with audience and orchestra interactions.

- The idea that the show is physically taxing for actors, in terms of dance and fight choreography.

With these changes, there have now become two different versions of the show that are available to liscense out to regional and community theatres. The Papp & Leach version is available through Music Theatre International, while Concord Theatricals has a more traditional version (more fitting with Gilbert & Sullivan's original concept). To illustrate the Papp & Leach version's power and influence, between its tenure on Broadway and in Hollywood, the show made a journey overseas to London's West End; with their Pirate King played by the one and only Tim Curry. In 1994, another production in Australia would crank the improv, fourth wall breaking, and source material mockery up to eleven, with Jon English as the piratical monarch.

Even up to the 21st Century, theatres and opera companies such as Paper Mill Playhouse in New Jersey, The Muny in Missouri, the Fifth Avenue Theatre in Washington, the Lyric Opera in Illinois, and the City Opera in New York have all done multiple productions of The Pirates of Penzance following Papp & Leach's version, and have consistently produced it again; being, sometimes, the only Gilbert & Sullivan show they've put on as of more current times; or, perhaps, The Mikado, decades beforehand. You can find a plethora of other examples of this one show's production history online, but I would like to go back to that hypothetical sacenario I talked about in the very beginning of this entire piece.

A musical theatre student receives the announcement of their school's upcoming Gilbert & Sullivan production. If you were this hypothetical student, what would be your immediate assumption of which show it would be, from their collection of works? That's how popular and culturally relevant The Pirates of Penzance has become. This one Off-Broadway, production, in 1980, who gambled it all on making their own rules on how to stage a Victorian classic, in order to make it accessible to modern viewers, over a century later, which paid off (immensely) and subsequently changed the entire identity of that "classic" in the process. HMS Pinafore and The Mikado are still seen as old school operettas, while The Pirates of Penzance has successfully evolved and been elevated to the status of a musical.

Compared to the veritable menagerie of adaptations of Tchaikovsky's 1892 ballet The Nutcracker every holiday season, they have all updated the material and gotten rid of the popular judgements that have determined what the "right way" is to produce a stage show; making them feel just as radical and fresh as the original version did. Such a transition I only wish could be done for the rest of Gilbert & Sullivan's material. with 13 other operettas in the public domain, the potential for reinvention and cultural redefinition is only limited by one's passion and creative perception of what's been handed down on the printed librettos and scores.

About the Creator

Jacob Herr

Born & raised in the American heartland, Jacob Herr graduated from Butler University with a dual degree in theatre & history. He is a rough, tumble, and humble artist, known to write about a little bit of everything.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insight

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Comments (1)

This is excellent and informative and fun, but I do like Gilbert and Sullivan