THE LIMITS OF KNOWLEDGE

The Uncertainty Principle

Andrea Moro and Noam Chomsky, In their new book The Secrets of Words, agree that humans cannot know everything. Something will always remain a mystery to human consciousness.

Now that we are in the early part of the 21st century, I can’t help but to think of the early 20th century, when physicists and scientists grappled with the acceptance that humans cannot know everything because nature or matter at its very core cannot yield its secrets.

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle unveiled a shocking truth about human’s ability to understand. This principle only became clear to quantum physicists in the 1920s, when they started looking inward at the atom and its core. That microscopic world is incredibly small, and the electrons and other particles within it are so miniscule that boggles the mind.

Niels Bohr (1885 – 1962) was a Danish physicist who made major contributions to the study of atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. After him, it soon became obvious that there was no way to scientifically figure out how that microscopic world worked.

It was like a physicist trying to investigate the works of a microchip by inspecting it with the tools of a blacksmith: hammer, anvil, and other equipment that could never let him see the inner works of the chip. An attempt by a physicist to open and study the chip would destroy it. Scientists with more advance instruments would also face the impossibility of the limits of knowledge.

Slowly, quantum physicists and other scientists accepted that nature itself embedded uncertainty.

Einstein, Heisenberg, and Max Born

Einstein did not like what some of his contemporaries were learning in the new concept of universal mechanics, he had helped to develop; It was a brand-new system based on quantum mechanics and randomness. Nature forced the quantum mechanist to embrace a basic element of unpredictability in theory.

The German physicist Werner Heisenberg (1901–1976) articulated “the fundamental Uncertainty Principle,” which bears his name, in 1927. Heisenberg says, according to this principle, it is impossible to calculate an object’s position and velocity at the same time.

The deeper truth was perhaps that the universe was a random universe.

Things caused this difficulty; matter itself, rather than anything else cause the unpredictability. Clumsy equipment (never completely accurate) attempted to measure what it could not measure.

Newton’s mechanics still apply to the world of large things, like flora, fauna, people, seas, mountains, or planets. But for tiny masses, like atoms and elementary particles, the uncertainty principle is significant and, so far, insurmountable.

When attempting to measure an extremely small object, such an electron’s velocity will push the electron around, making it tough if not impossible to determine its position, even in theory. Other observable pairs also contain the uncertainty, most notably energy and time. There will be some ambiguity over the lifetime of the unstable system as it changes to a more stable state if one attempts to precisely quantify the energy radiated by an unstable nucleus, for example.

His uncertainty principle did not trouble Heisenberg, but it surely disturbed Einstein greatly. He was wont to say that “God is subtle, but he is not malicious.” Einstein spent the last years of his life struggling vainly to disprove Heisenberg. But he failed. The physicist Max Born (1882 – 1970), said: “Many of us regard this as a tragedy, both for Einstein as he gropes his way in loneliness, and for us, who miss our leader and standard-bearer.”

But why was Einstein so disturbed by the Heisenberg Principle? The answer may be in his religion. He believed in a benevolent God that didn’t play dice with the universe. One had to make nature yield its secrets by mathematics. To Einstein, the uncertainty principle was in fact a throw of the dice.

Conclusion

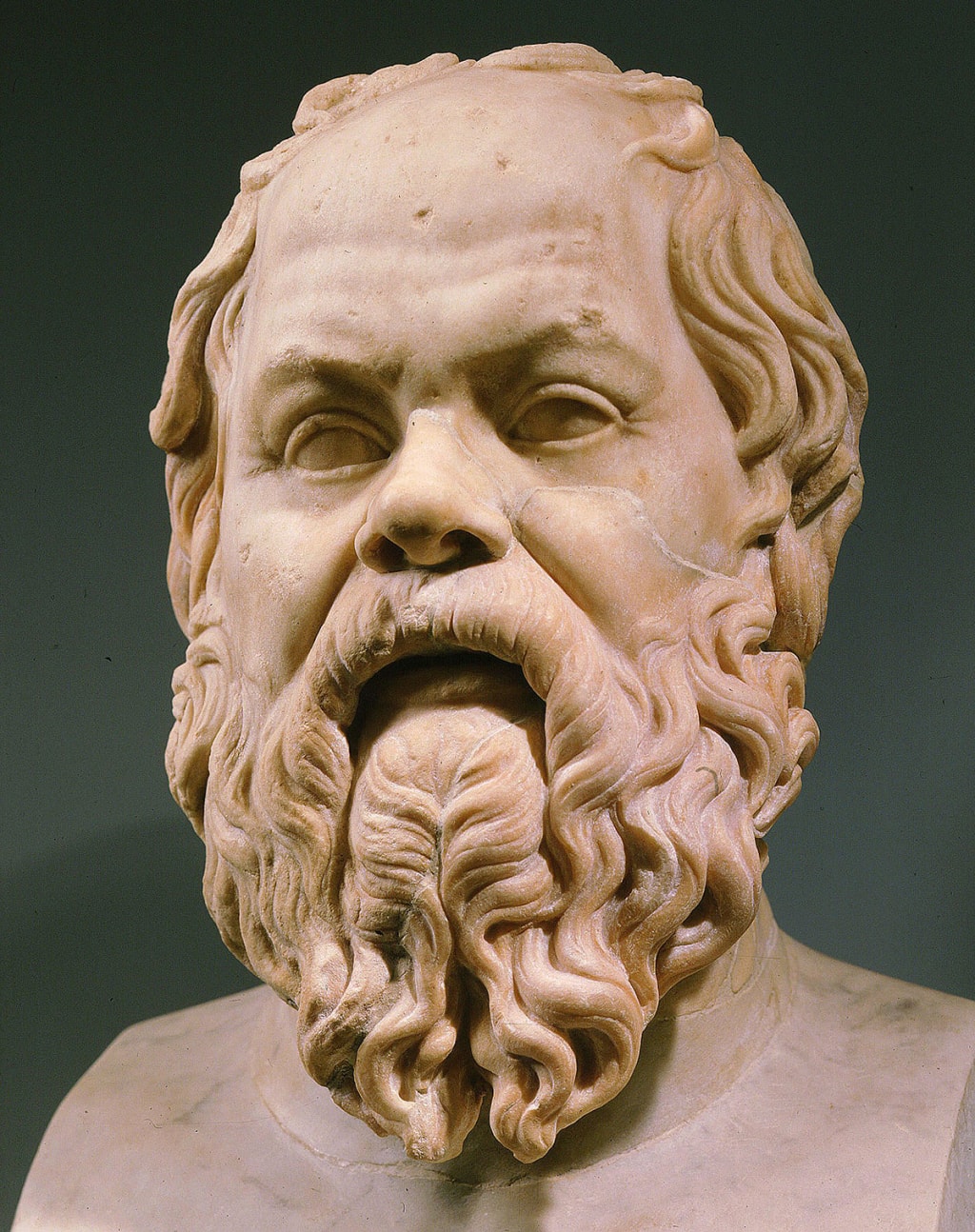

So, like a dog that chases his own tail, we return to what Andrea Moro and Noam Chomsky, both linguists, said in their discussion of human knowledge: not everything can be known. Something will always remain a mystery to human consciousness. I smile because I cannot help but to think of what Socrates and Plato both said 2500 years ago: “The only true wisdom is in knowing you know less than a subatomic micro particle-- nothing really.”

Find three of my books below:

<a href="https://www.etsy.com/shop/Digitaltopos"></a>

My articles are first written by Writesonic (AI) and then I edit them. Of all the AI software out there, Writesonic is the best and most economic.

https://writesonic.com?via=marciano89

About the Creator

Marciano Guerrero

Marciano Guerrero is a Columbia University graduate, retired business executive, retired college professor, and a disabled Vietnam Veteran. I enjoy writing fiction, and essays of human interest. I also have a keen interest in AI.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.