guy see mee as These were tough old vicez of the 19th century, like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth (note:

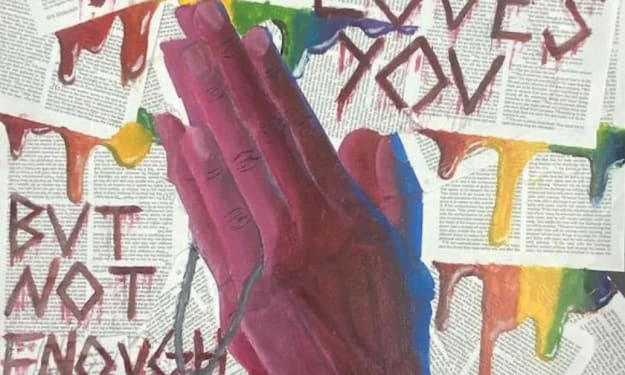

women, rather ironic to call ``bitchez'' in affectionate z higher-level material is - perhaps sticking to "women" for now) All Cady Stanton: "Brothers who thought you could get voting rights and such if you weren't busy." continued to commit sincere shit until the 19th Amendment, which gave American women the right to vote, was ratified in I was still pretty obsessed with the idea that it was all about silently scrubbing things up... but hey, nobody's perfect. you know what? you are a feminist If you're a living person in the world, people, both men and women, are saying all feminists are hairy, reactionary, undersexual, misanthropic complaints who need to stop crying (Because we have the right to vote now!) Feminism Feminism is simple. Rights and Opportunities. Being a feminist also means acknowledging that the world is not a fair, just and safe place for women right now. Obviously (see:

everything ever). To deny these things makes you, at worst, a bad person who hates women, including but not limited to:

Sarah Michelle Gellar, Jennifer Garner, Jennifer Aniston, Jennifer Lopez, your mother, Jennifer Lopez's mother, Jennifer Garner's Aunt Marcy, Michelle Obama, Ellen DeGeneres, Cher, Julie Andrews, Kim Kardashian, Khloe Kardashian, Kourtney Kardashian, Kraken Kardashian, Karphone Kardashian, Kickball Kardashian, Kornkob Kardashian

Second-Wave Feminism:

Maybe You Could Stop Raping Us, Please?

After World War II, women started to be like, "Oh! Maybe I can get a job and tell my husband to stop raping me!" They began taking on subtler forms of sexism and misogyny—things that might not be legally mandated (like voting rights) but were fucking up women's lives nonetheless. These women would become the second-wavers. In 1963, Betty Friedan made everyone go crazy by suggesting that the nuclear family might be a crock of shit that stifled women's potential and made them unhappy. Birth control pills, legalization of marital rape (in every state, finally in 1993!), Griswold v. Connecticut, Affirmative Action Rights for Women, Title IX , Roe v. Wade, and more on Wikipedia. (Fun fact:

bras weren't actually burned.) There was a lot of discussion (zzzzzz) about porn. The Equal Rights Amendment was not passed. When the shit started, savvy anti-feminists made sexism official because women were no longer (sometimes) allowed to be raped and could even work for low wages in clothing factories and rape advertising agencies. I got the chance to declare From that moment on, everything was a hairy braless woman. Women kept fighting because women are great. Screw Phyllis Schlafly.

One day someone pointed out that the word "woman" encompasses more than just "disgruntled middle-class white housewife." I have an immigrant woman. Some are trans women. There is a middle class white housewife who is utterly dissatisfied. I have a sex worker. Third Her Wave Her feminism is the idea that women can and should define their own femininity. With a million different types of women out there, the third wave could be big, a little confusing and confusing, or not exist at all (history is a continuum.feminism

The second wave of feminism

The women’s movement of the 1960s and ’70s, the so-called “second wave” of feminism, represented a seemingly abrupt break with the tranquil suburban life pictured in American popular culture. Yet the roots of the new rebellion were buried in the frustrations of college-educated mothers whose discontent impelled their daughters in a new direction. If first-wave feminists were inspired by the abolition movement, their great-granddaughters were swept into feminism by the civil rights movement, the attendant discussion of principles such as equality and justice, and the revolutionary ferment caused by protests against the Vietnam War.

Women’s concerns were on Pres. John F. Kennedy’s agenda even before this public discussion began. In 1961 he created the President’s Commission on the Status of Women and appointed Eleanor Roosevelt to lead it. Its report, issued in 1963, firmly supported the nuclear family and preparing women for motherhood. But it also documented a national pattern of employment discrimination, unequal pay, legal inequality, and meagre support services for working women that needed to be corrected through legislative guarantees of equal pay for equal work, equal job opportunities, and expanded child-care services. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 offered the first guarantee, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was amended to bar employers from discriminating on the basis of sex.

Some deemed these measures insufficient in a country where classified advertisements still segregated job openings by sex, where state laws restricted women’s access to contraception, and where incidences of rape and domestic violence remained undisclosed. In the late 1960s, then, the notion of a women’s rights movement took root at the same time as the civil rights movement, and women of all ages and circumstances were swept up in debates about gender, discrimination, and the nature of equality.

Dissension and debate

Mainstream groups such as the National Organization for Women (NOW) launched a campaign for legal equity, while ad hoc groups staged sit-ins and marches for any number of reasons—from assailing college curricula that lacked female authors to promoting the use of the word Ms. as a neutral form of address—that is, one that did not refer to marital status. Health collectives and rape crisis centres were established. Children’s books were rewritten to obviate sexual stereotypes. Women’s studies departments were founded at colleges and universities. Protective labour laws were overturned. Employers found to have discriminated against female workers were required to compensate with back pay. Excluded from male-dominated occupations for decades, women began finding jobs as pilots, construction workers, soldiers, bankers, and bus drivers.

Unlike the first wave, second-wave feminism provoked extensive theoretical discussion about the origins of women’s oppression, the nature of gender, and the role of the family. Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics made the best-seller list in 1970, and in it she broadened the term politics to include all “power-structured relationships” and posited that the personal was actually political. Shulamith Firestone, a founder of the New York Radical Feminists, published The Dialectic of Sex in the same year, insisting that love disadvantaged women by creating intimate shackles between them and the men they loved—men who were also their oppressors. One year later, Germaine Greer, an Australian living in London, published The Female Eunuch, in which she argued that the sexual repression of women cuts them off from the creative energy they need to be independent and self-fulfilled.

Any attempt to create a coherent, all-encompassing feminist ideology was doomed. While most could agree on the questions that needed to be asked about the origins of gender distinctions, the nature of power, or the roots of sexual violence, the answers to those questions were bogged down by ideological hairsplitting, name-calling, and mutual recrimination. Even the term liberation could mean different things to different people.

Feminism became a river of competing eddies and currents. “Anarcho-feminists,” who found a larger audience in Europe than in the United States, resurrected Emma Goldman and said that women could not be liberated without dismantling such institutions as the family, private property, and state power. Individualist feminists, calling on libertarian principles of minimal government, broke with most other feminists over the issue of turning to government for solutions to women’s problems. “Amazon feminists” celebrated the mythical female heroine and advocated liberation through physical strength. And separatist feminists, including many lesbian feminists, preached that women could not possibly liberate themselves without at least a period of separation from men.

Ultimately, three major streams of thought surfaced. The first was liberal, or mainstream, feminism, which focused its energy on concrete and pragmatic change at an institutional and governmental level. Its goal was to integrate women more thoroughly into the power structure and to give women equal access to positions men had traditionally dominated. While aiming for strict equality (to be evidenced by such measures as an equal number of women and men in positions of power, or an equal amount of money spent on male and female student athletes), these liberal feminist groups nonetheless supported the modern equivalent of protective legislation such as special workplace benefits for mothers.

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.