How to Use the X-Bar Theory to Make Learning Grammar a Piece of Cake

Grammar is not a pile of random rules.

In a very important aspect, traditional grammar textbooks often fail you.

You open that book (or click on that article) that is supposed to teach you the grammar of your target language... and you're confronted with a mumbo-jumbo of bizarre rules, each with a dozen nuances you need to take into account, as well as a whole list of exceptions that, you are told, cannot be understood, only memorized.

Most of the time, that is wrong. It's just that most people approach this grammar thing wrong simply because they haven't been given the right tools. You are taught all kinds of details, while the bigger picture, the framework of what is actually going on, is missed. You may get a gist if you're smart, and you'll probably be given a few tools, but that's not effective.

Let's try to fix that, shall we?

And for that reason, let us explore some basic generative linguistics (since I only know the basics myself but trust me, they've been of great help).

But first of all, we need to understand what's wrong with the classic approach.

It's about structure

I've been learning German recently, and having learned about X-bar structures in the syntax chapter of my introductory linguistics textbook, I decided to try applying it to my target language for fun (and understanding, too, of course), so I decided to try to get the hang of the German sentence structure early as a beginner so that I would have a framework that would help me understand and form new sentences.

With all those "random" word order rules, I can't say for sure that I wouldn't have given up halfway and decided to just learn it through immersion eventually if I didn't know X-bar. Maybe my innate love for grammar would have sustained the passion, I don't know. But I did know X-bar, at least, enough basics to figure the specifics out myself, and let me tell you, unlike the article made it seem, it was a piece of cake.

So what do they do wrong?

The problem is that when analyzing word orders, people focus too much on order, structure, and linearity. But language is not about a sequence of words.

Let's consider an ambiguous sentence. The bandits beat up a man with a walking cane. (- Why so violent, Ju? - Cause seeing people with binoculars is too much of a classic. Anyways,) Is it that the man was beaten using a walking cane, or is the cane supposed to be just a defining characteristic of that man, who may have been beaten with bare fists or whatever? The sentence is ambiguous because there are two possible structures: in the latter case, a man with a walking cane forms a unit, while in the former, beat up with a walking cane does. Meaning, sentences are not understood by analyzing sequence. Meaning is expressed through structure, and the sequence of words, along with morphology, is just a way to convey said structure.

Now, before we dive right into those structures, let's make sure that we understand the visual representation we are going to use for this purpose, tree structures.

Now this is a very general tree structure taken from Wikipedia:

A tree is an abstract data type that represents hierarchy as connected nodes (the numbered circles). Each node can have one or more children, meaning, they can be connected to as many lower nodes as possible (for example, 5 and 11 are children of 6 in the tree above). Meanwhile, each node has exactly one parent, or node above them (6 is the parent of 5 and 11), except for the root node (the green 2 in the red circle), which has none. Children of the same parent are called - you won't believe me - siblings.

Ok, now that we're on the same page, let's plunge into syntax, the study of sentence structure.

The building block of sentence structure is a phrase, which can be as short as a word and as long and complex as a page-long sentence. No matter the complexity, though,

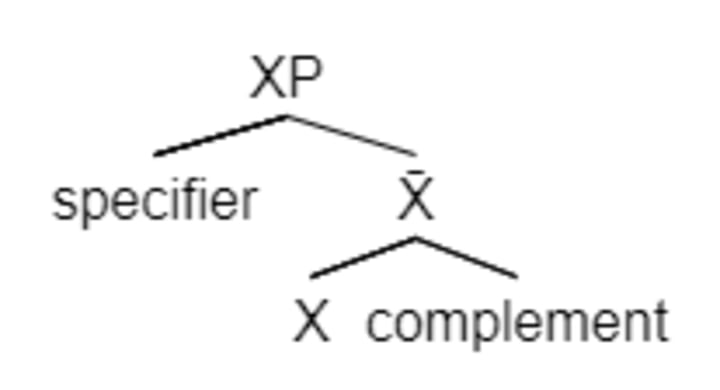

all phrases in all languages look like this:

Don't worry, we'll get there.

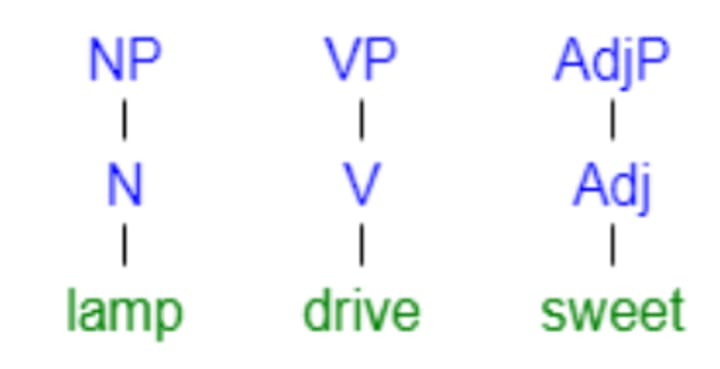

Let's start with the smallest phrase possible, the kind that consists of a single word, like lamp or drive, or sweet.

Lamp is a noun and the head of its own tiny noun phrase, or NP in short, consisting of a single noun. Drive, a verb, is the head of a verb phrase (VP), obviously, and sweet, the adjective head of a single-word adjective phrase (AdjP, so as not to confuse it with an adverb phrase, or AdvP). Or, if we generalize it, any word that contributes any meaning to the sentence (not a conjunction or interjection) that belongs to X part of speech is the head of its X phrase, or XP for short.

So, for now, we have three phrases:

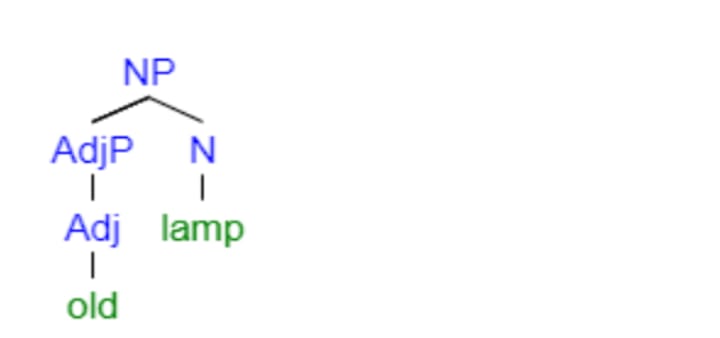

Obviously, we don't communicate in single-word phrases. Let's add a modifier to the NP, like old lamp. Very creative, I know. Now we have an adjective or, actually, a single-word adjective phrase (AdjP, so as not to confuse it with an adverb phrase, or AdvP) modifying our noun head.

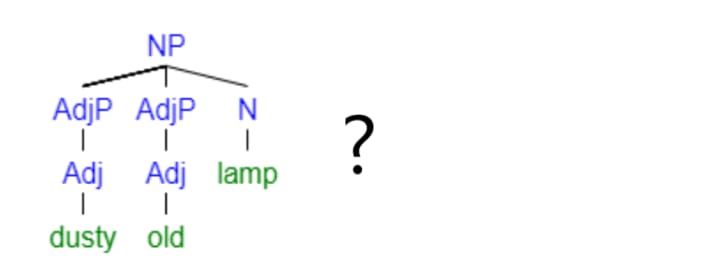

We can add another adjective, like dusty old lamp. What happens now, is it

Not really. Here we are falling into the old linearity pitfall again.

If you put your language speaker's intuitions to use, you might notice that these words are not really on the same level in terms of hierarchy; rather, old lamp forms a kind of unit and that dusty modifies not only the noun head lamp but also old lamp as a whole, as you could say that there are various kinds of old lamps: a yellow one, I mean, a yellow old lamp, a dusty old lamp, a clean old lamp, etc. Actually, the fact that I could replace old lamp with one in a yellow one suggests that this head-complement complex functions as a unit.

In tree structures, a head-complement complex is represented by an X (or N, V, Adv, Adj, etc) with a bar over it, or X̄, hence the name of the theory we're talking about right now, the X-bar theory. However, I'm way too lazy to search for capital letters with bars over them every time I want to draw a phrase (since every phrase has an X'), so I will add ' to the letter instead, as in X', N', V', Adj', etc. I've seen others do that, so why not. Each head-complement complex functions as a relative head to its sibling called the adjunct.

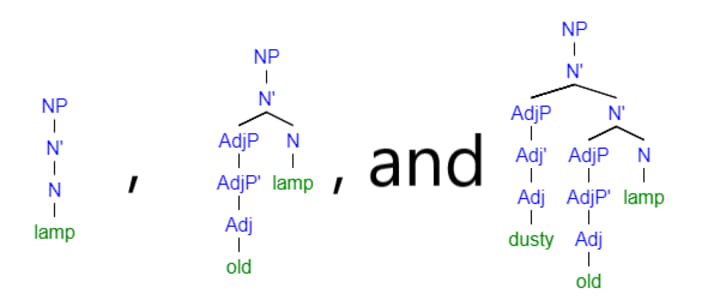

Thus, the actual structures of lamp, old lamp, and dusty old lamp would look like

respectively. Notice that even a single-word phrase consists of a (one-word) head-complement complex. The property of some phrases that allows them to have multiple modifiers and a long string of sausages head-complement complexes like the NP and VP in the example below is called recursiveness and the fact of it happening is recursion.

Great, so now we have phrases consisting of heads, complements, complements of head-complement complexes called adjuncts, and... what's that specifier thingy?

There is something we've avoided adding to the NP till now. In English, we don't usually say dusty old lamp alone, do we? We say that this is a dusty old lamp, the, that, this, or grandma's dusty old lamp. Another thing you might notice is that you can say either the dusty old lamp or grandma's dusty old lamp, while *grandma's the dusty old lamp or *the this dusty old lamp sounds like the speaker may be having a stroke. Besides, you couldn't really say that this determiner is adding nuance or quality to the thing that the head is referring to in the same way an adjective does to the noun head: it is specifying which dusty lamp it is.

Thus, we can conclude that there's a special type of modifier, a specifier, and that this member of the phrase is not recursive, which means that it's not under the head-complement complex but is directly subordinate to the whole phrase.

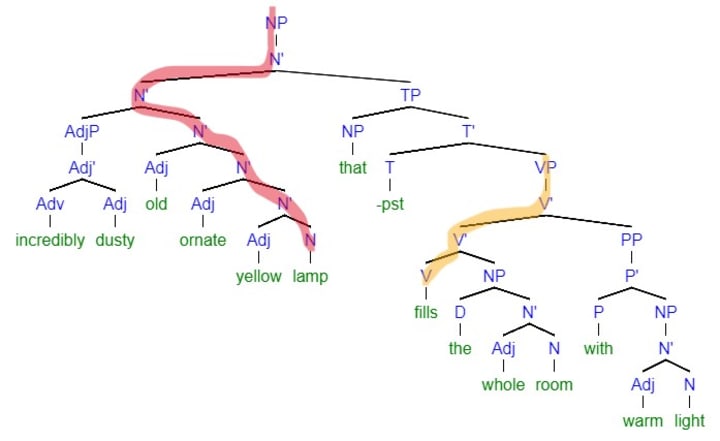

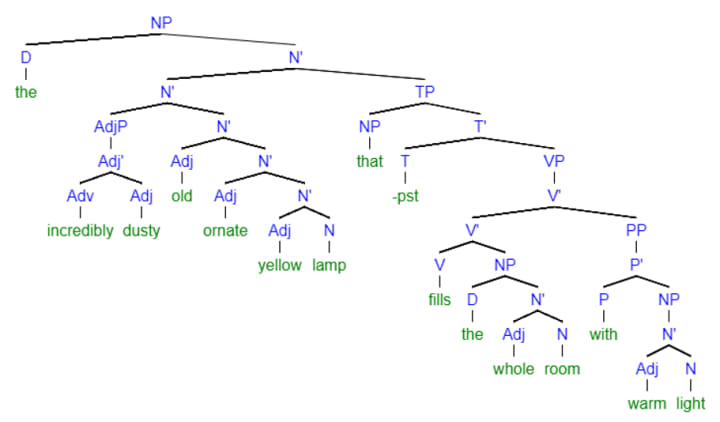

Thus, we have arrived at the complete structure of the phrase, so let me add the specifier the to incredibly dusty old ornate yellow lamp that fills the whole room with warm light:

Now that we have the basics, we can move to yet more interesting stuff and explore how the X-bar framework allows for enough flexibility to represent any phrase in any language. First of all,

What kinds of phrases are there?

Though all phrases in all languages have the same underlying structure, there are differences in

- the complements they may take on,

- whether or not they are recursive,

- whether or not they have what kinds of specifiers

- head-complement directionality (which comes first, the head or the complement),

- the morphological properties that express syntax,

and so on.

One of the two most important phrases is

The noun phrase

Noun phrases can be substituted by whole pronouns: my grandmother's lamp --> it; that girl in the red dress --> she etc. In that case, the pronoun stands for the whole phrase (see NP - that in the previous picture).

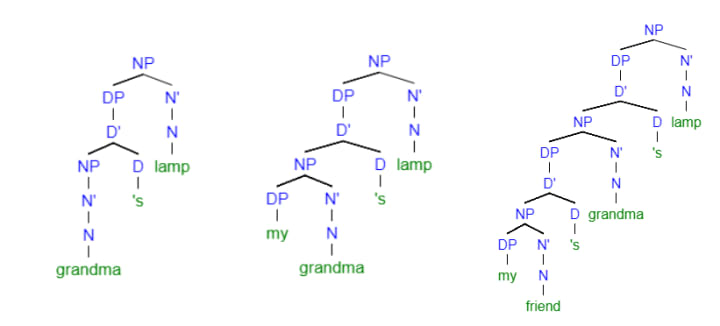

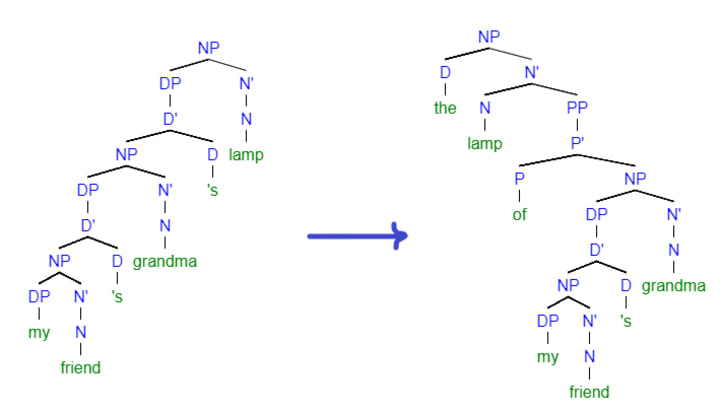

The specifiers of NPs are determiners, which, naturally, have their own determiner phrases (DP). Besides pointing at stuff with the determiners a, the, that, this, the English also use DPs to express possession in phrases like

DPs are not recursive, but, as you see in the picture above, the NPs inside them can have specifiers DPs with NPs inside of them that have DPs with NPs inside... and so on.

In the third phrase, my friend's grandma forms a unit, and that could be proven by moving the NP to a preposition phrase (PP): my friend's grandma's lamp --> the lamp of my friend's grandma.

When this NP is put inside a DP with 's as its head, you get the possessive form.

The complements and adjuncts of NPs can be adjective phrases (AdjP), preposition phrases (PP), numerals, and even other NPs.

The latter deserves some additional note. In English, we distinguish between the head noun and its nominal modifier by taking note of the word order - head comes last - and the lack of the plural marker (suffix) on the modifier. For example, in human beings, the beings are humans but since the word humans modifies beings, the plural marker is lost and what you get is human beings, not humans beings.

In many other languages, NPs modifying other NPs, whether as specifiers or complements, take on a marker of a case called the genitive. For example, in Latvian, my native language, a grandma is called vecmāmiņa (literally oldmommy) and a lamp is a lampa (obviously borrowed). Grandma's lamp, then, would be vecmāmiņas lampa. The -s in this case is a genitive suffix, marking the fact that the noun vecmāmiņa is modifying lampa.

Likewise, in medical Latin, a groove is called sulcus, and the ulnar nerve is called nervus ulnaris, while the groove for the ulnar nerve is called sulcus nervi ulnaris. The -i in nervi and -is in ulnaris are genitive suffixes as well (though -is is shared by both the nominative, or the normal case, if you will, and the genitive). Also, notice that the word order here is the opposite: complements come after the head noun, so Latin NPs are head-initial.

Besides cases other than genitive, which we are going to have a look at later, this is the most important stuff about noun phrases (in isolation), and if you need anything more, you can always read some deeper-level material or reinvent the wheel yourself (yeah, that's legal). However, a noun is usually not enough to express an idea: what you need is a predicative as well. And predicatives are verbs, so we need to talk about

The verb phrase (VP)

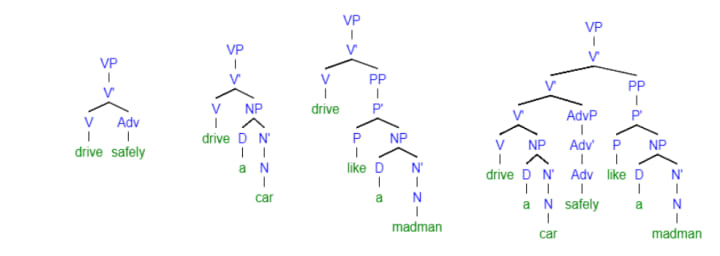

Let's take the verb drive and modify it.

We can add an AdvP, as in drive safely, a NP (drive a car), or a PP (drive like a madman), or, since the VP is recursive, all of the three, as in drive a car safely like a madman, as much of a cognitive dissonance its meaning requires.

Besides verbs, adverbs also modify adjectives and other adverbs and are not recursive, while preposition phrases (also not recursive) can modify all kinds of parts of speech but always take a NP complement (I apologize for the a in this situation but but I always read these abbreviations as the full terms). Noun phrases can modify verbs both as complements and as specifiers, and this will be important in building sentences.

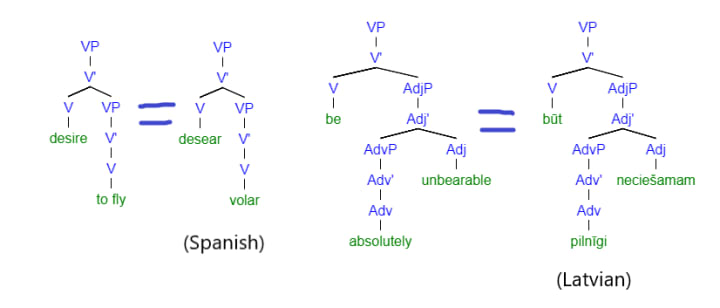

Specific verbs can take on VP complements like desire to fly, while the verb be can also take on an AdjP complement, as in be absolutely unbearable.

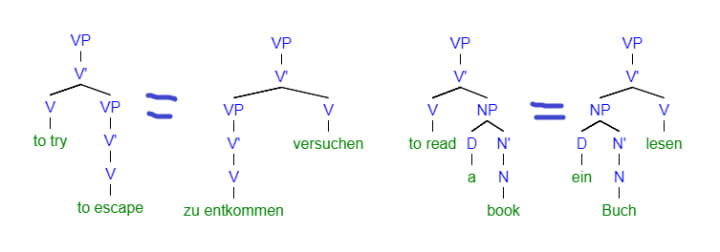

In English, VPs are head-initial, meaning, the verb comes first and then do the complements (generally). Meanwhile, German VPs are strongly head-final, so instead of saying to try to escape, they would say something like to escape try, or zu entkommen versuchen. Understanding this principle makes learning German sentence order much easier, as you realize that it's not simply that different situations trigger different word orders, it's that the verb is always in this position, except it has to move in the presence of certain parameters we'll touch on later, and the move is always the same.

Let's move on.

What makes a sentence

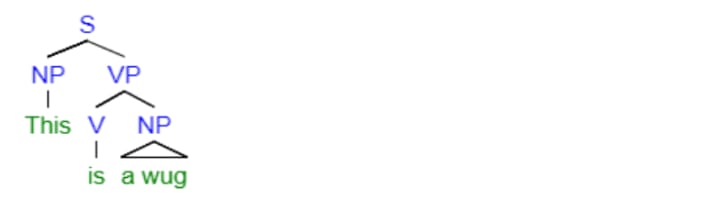

You might have heard of subjects, predicatives (often simply called verbs), and objects. Linguistics textbooks may speak of sentences consisting of NPs and VPs like this:

From the perspective of the X-bar theory, that's too linear and misses out... again, the structure, even though it's an attempt to understand it.

Let's build the sentence starting from the verb.

First, you need to understand that not all phrases, not even those we've looked at by now, are as tangible as you might think, 'tangible' meaning that it consists of actual words. There are specific heads and whole phrases whose purpose is to convey more abstract information related to syntax and morphology (the structure of words). In fact, much of morphology is syntax, except the "phrase" is a word and its members are morphemes. A morpheme is the smallest unit that adds information, whether semantic (meaning) or syntactic (structure).

So let's start with a VP.

Usually, when you hear a sentence, the verb phrase is not in the infinitive form. To drive a car is not a (complete) sentence. Rather, the verb is inflected depending on two main aspects: tense and person. In the X-bar theory, we explain it with the tense phrase (TP).

The head of a tense phrase is most often an abstract parameter such as the past (+pst) or the present (-pst, meaning, not past) but its effects are nevertheless quite tangible, resulting in a change in the verb. For example, the phrase drove a car would look like this:

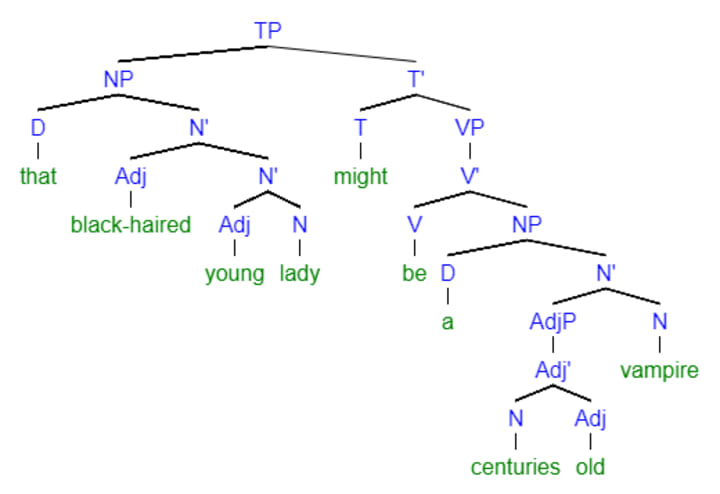

At other times, T can be a modal verb, like can, may, might, must, etc, as in

Now what about the subject? Intuitively, we feel that the he in he drove a car doesn't directly modify the verb phrase, nor does the verb modify the NP; rather any sentence consists of a NP and a VP of equal hierarchical position unless one of these is missing. That's the aspect in which the first tree in this section (This is a wug) is right.

However, as we now know, inflected VPs live inside a TP, and the kind of structure presented in said wug tree does not function like a phrase should in our framework. However, since we know that the head-complement complex of the tense phrase (T') is occupied by T and VP, we can figure out that NP should occupy the sister of T', namely its specifier. Thus, the TP contains the whole clause and all the parameters that affect the verb form, and the NP is on the same hierarchical level as T'.

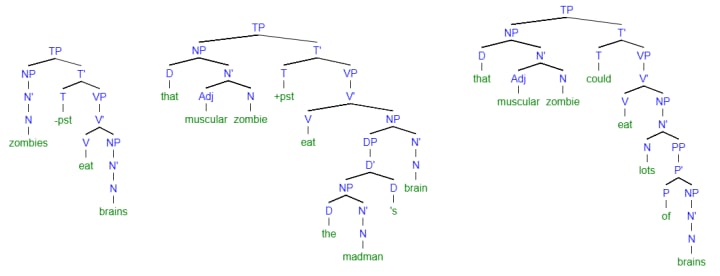

Now, we can draw some sentences like

- Zombies eat brains.

- That muscular zombie ate the madman's brain.

- That muscular zombie could eat lots of brains.

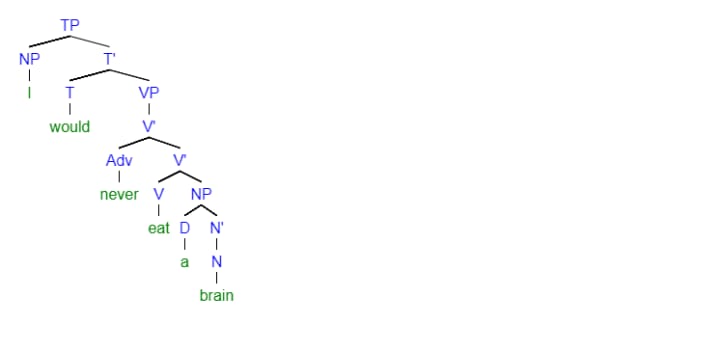

and

- I would never eat a brain.

Besides this, the TP proves useful in explaining modal verbs, complex tense structures (e.g., perfect tense), and some curious morphological structures like participles, which are adjective/adverb-like words made of inflected verb forms. But that's a story for another time.

Roles of NPs in a sentence

I promised that we would look at an important aspect of morphosyntax (the relationship between the structure of words and that of whole sentences), namely case.

Depending on their relationships with the other words, NPs can have various roles in a sentence. Here are the most important relationships a noun can have with the main verb (the predicative).

- The subject of a sentence is typically described as the agent, or the 'doer' that does something (verb) to an object. Although this description may help our language intuitions identify a subject, this view is quite oversimplified, as a single grammatical element can have quite varied roles in terms of meaning. Still, as we have figured out by now, all subjects, which are mostly NPs but, depending on the language, can also be AdvP or even whole clauses, are specifiers of the TP (e.g., zombies in zombies eat brains). In languages where noun inflection is a thing, the marker (like a suffix) that denotes that the noun is a subject is called the nominative case. The nominative, as its name suggests (Latin nōminō - to name), is also often the base form of a noun, or the case used to name things when no grammatical relations are involved.

- The NP complement of a verb is called the direct object, the one directly acted upon by the subject. Thus, brains is the direct object in zombies eat brains. Verbs that can have an object are called transitive, for example, drive, eat, and love are transitive since they can take on a direct object, as in drive a car, eat brains, and love ice-cream. Words that cannot take an object are called intransitive (duh). Direct objects take on accusative markers.

- So far, we haven't covered one position, the specifier of VP. That's where the indirect object goes, taking on the dative (Latin dare - give) marker if such exists in the language. As the name dative suggests, give is a typical example of a ditransitive verb, meaning, a verb that can take two objects, both a direct one and an indirect one, as in he gave his mom (indirect object) a present (direct object) on her birthday. The indirect object isn't acted upon in a, well, direct manner, rather, the indirect object is kind of standing on the side and receiving the effects of the actions.

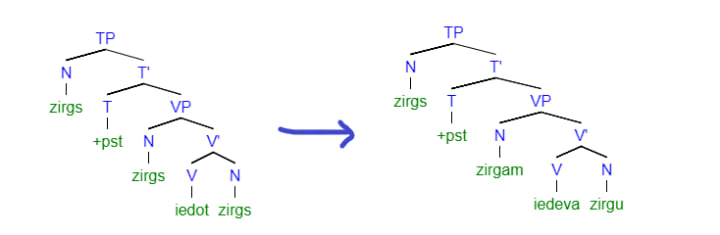

To illustrate case markers, here's the incredibly deep and meaningful sentence A horse gave a horse a horse in Latvian:

Zirgs iedeva zirgam zirgu.

Zirgs is the subject of a sentence, and this is marked by -s, the masculine nominative ending of first-declension nouns. (Declension as a process is the inflection (case-ing) of nouns, while a declension is a group of nouns declined according to the same pattern.) The indirect object of the sentence is zirgam, marked by the dative ending -am. The direct object, zirgu, is in the accusative case, as marked by the suffix -u.

By the way, Latvian has seven cases: besides nominative (subject), genitive (noun modifying another noun), dative (indirect object), and accusative (direct object), there's also the instrumental, used for complements of specific prepositions, such as with, and the locative, which, of course, indicates location, eliminating the need for all the confusing in's and at's.

What's the use of all these cases?

Besides making it easier to convey the message with clarity (just look at the suffix and you know the role of the word in the sentence), case systems allow for far greater flexibility in word order. English speakers rely greatly on word order to make their point clear and to understand what's being said, so a horse a horse gave a horse sounds more like the mutterings of a madman than an actual sentence. In Latvian, meanwhile, all the following sentences are equally clear and acceptable:

- Zirgs zirgam iedeva zirgu.

- Zirgam zirgs iedeva zirgu.

- Zirgs zirgu zirgam iedeva.

- Zirgam iedeva zirgs zirgu.

- Zirgam zirgs zirgu iedeva.

- Iedeva zirgs zirgu zirgam.

- ...

Ugh, my head is spinning from all the zirgi (nominative plural).

Anyways, due to the cases, the relation of each zirgs with the rest of the sentence is clear, so there are 4!=24 possible word orders for the same structure:

Though some of these word orders may sound a bit awkward, especially out of context, as some orders are more common than others, they are all valid. Actually, the fact that some word orders are more neutral and others, less so, allows for word order to work alongside intonation to add nuance to the sentence by emphasizing certain parts of it. Usually, the main emphasis goes to the last word. English speakers can still express the same kind of nuance by using stress or different verb forms, but in Latvian, there are more tools for indicating emphasis even in written text.

Now, we understand the basics of sentence structure. However, as we just saw, the word order of the sentence may not be the same as that of its members in its X-bar tree. Besides, in some situations, we can move an element by following some specific rules. Here are a few examples:

- There are five churches with a rooster on top of the bell tower in Riga. → In Riga, there are five churches with a rooster on top of the bell tower.

- She still sometimes struggles with procrastination. → Sometimes she still struggles with procrastination.

- I have never lied to you. → Never have I lied to you.

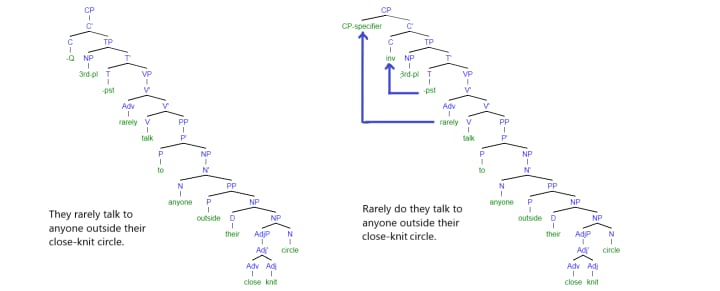

- They rarely talk to anyone outside their close-knit circle. → Rarely do they talk to anyone outside their close-knit circle.

In the last example, not only does the word order change but a whole new word appears when you change the word order. The grammatical relations are still the same but we can't draw a normal tree of this, or can we? What's going on here?

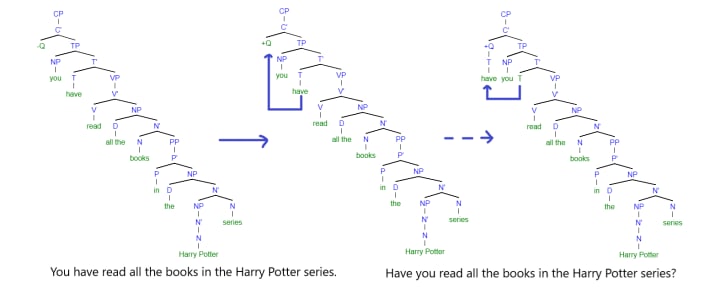

Besides, so far we've only looked at affirmative statements (no questions and no negations). Yet we know that there's a connection between "Nettle soup is heavenly." and "Is nettle soup heavenly?", as well as between "The horse gave the other horse a horse." and "Did the horse give the other horse a horse?"

To understand this phenomenon, we need a new phrase and a function.

Will you move over, please?

There's more to a sentence than just content. Each sentence has a syntactic quality that determines whether it's a statement or a question and whether it's a main clause or a subordinate one. Depending on the language, this property can mess with the usual word order, making it differ from the deeper structure.

This property is determined by the complementizer phrase (CP). Complementizer phrases have TPs as complements, and, as for the head, it can be either an abstract component indicating whether the sentence is a statement or a question, or whether it has a specific change in word order in comparison to the most common order for statements, or a subordinate conjunction introducing a subordinate clause.

Let's look at each option in more detail.

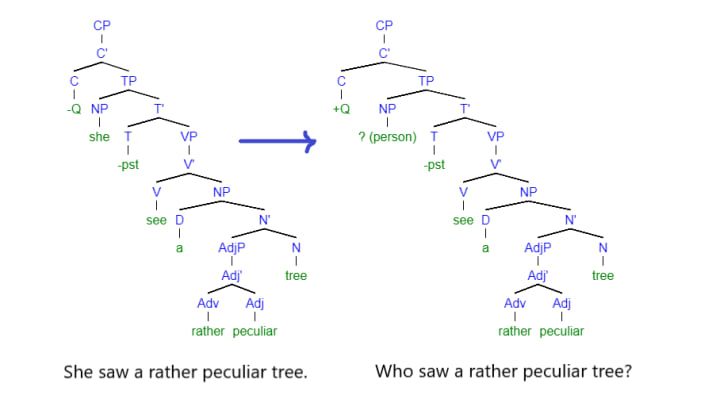

Statements ↔ questions

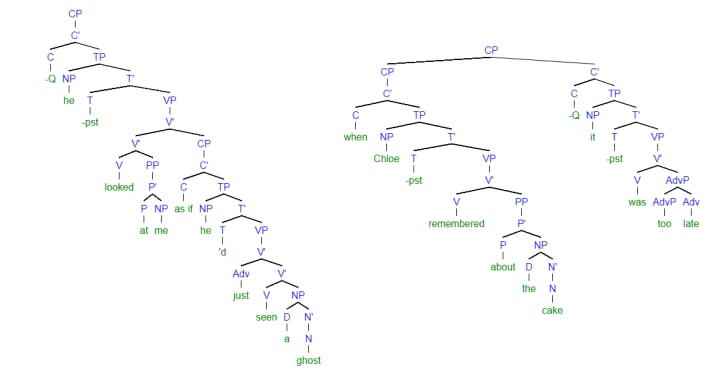

When there's no question, no weird inverted orders, nothing of the sort, and the clause is not inside another clause, you have the basic structure of a main clause, and the head of the CP is written as -Q to indicate that there is no question (+Q) property to the sentence, meaning, the sentence is a statement.

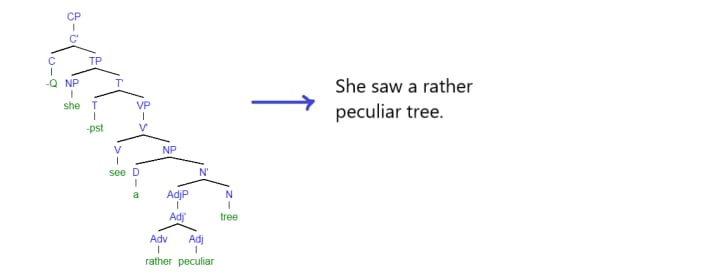

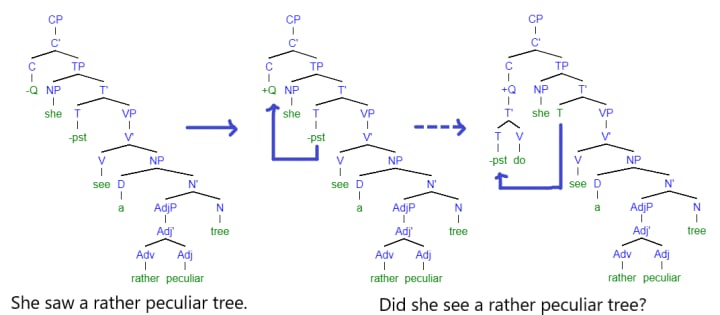

Adding the question property to the sentence (C=+Q) causes specific changes, depending on the language. Sometimes a question can be made using intonation alone, as in You haven't seen a single Star Wars movie??? Often, a question word is used, and the word order of the sentence may change, occasionally with a modal verb popping up in a specific, rule-governed position:

- That is so terrible. → Is that so terrible?

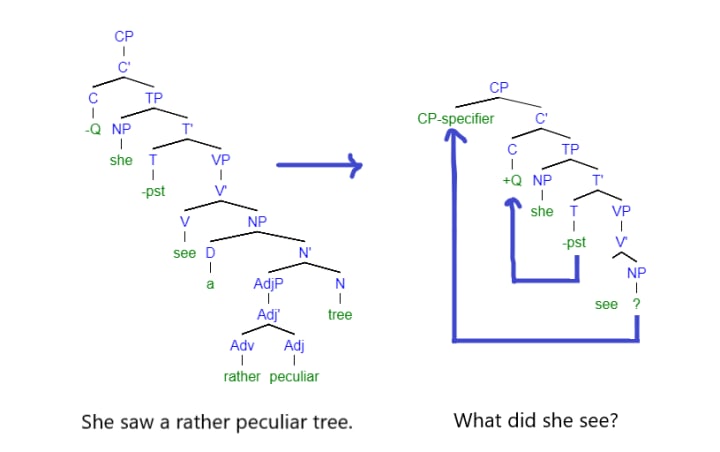

- She saw a rather peculiar tree. → Who saw a rather peculiar tree? What did she see? Did she see a rather peculiar tree?

What happens is that in English, C=+Q causes movement. The first move that happens is that T (tense) moves to the position of C (the head of CP):

When the T moved is abstract (just tense, like +/-pst) is moved, it has to be realized as the modal verb do:

When we want to ask an open question in English about a specific member of the sentence, we

- replace that phrase with a question word;

- (typically) move it to the beginning of the sentence.

Subjects in English need no moving, as they're already there.

Meanwhile, if you're asking about a modifier of V, it has to move. Move where, though? We've learned that T moves to the position of C. What could stand even before C? The specifier of C. The specifier of the complementizer phrase is a structural slot where verb complements and adjuncts can be moved if the C in a specific sentence requires it in the language.

The type of question word used depends on the type of phrase the answer expects and maybe a few more specific details:

- You used to drink coffee [every day]. → How often did you use to drink coffee?

- You got rid of the dependence [by fixing your sleep schedule]. → How did you get rid of the dependence?

Word order

Sometimes, we don't even need to make a question for the sentence order to change. Sometimes the order can be inverted (C=inv), as in

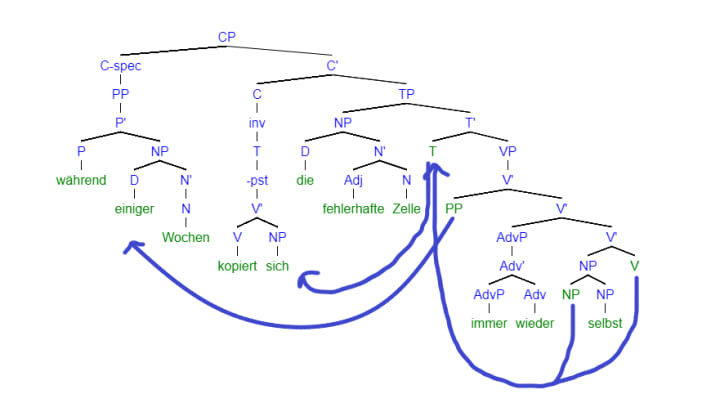

In English, inverted structure is pretty rare and mostly reserved for specific phrases, while in German, any sentence with a subject, an object, and a verb can be inverted by moving

- any complement/adjunct of the main V to the specifier of CP

- T, which automatically contains the main V (as well as a pronoun modifying V if such is present) in main clauses, to C.

Here's an example:

This simple phenomenon explains many of the confusing word order rules that seem to boggle those learning the language, and I'd love to explain my system for German sentence structure in a future article.

Subordination

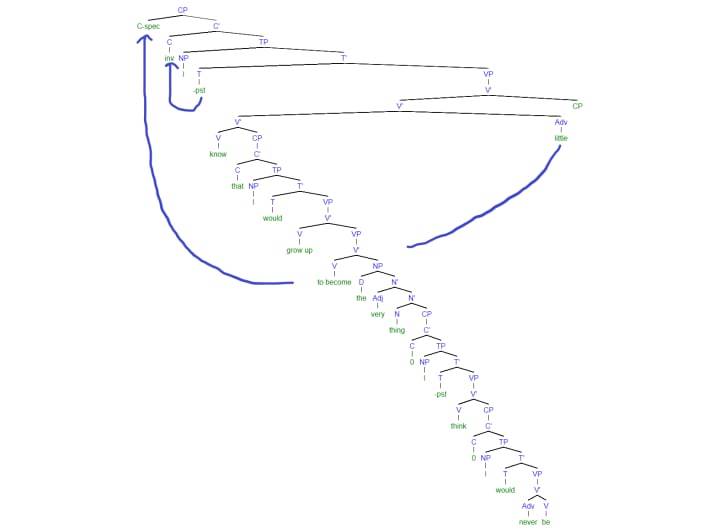

Here's the X-bar tree of Little did I know that I would grow up to become the very thing I thought I'd never be.

Several things are going on here.

- The huge subordinate clause (CP inside the main CP) functioning as the object moves to the end of the main verb phrase, or, in terms of structure, to the upper adjunct where subordinate CPs often like to move so that they wouldn't break up the bigger clause, at least they do so in English and German. Humans can only hold so much working memory in their minds, so returning to the main clause after finishing the subordinate one could lead to confusion. Thus, this type of movement is meant to make processing the sentence easier (as do most, if not all, grammar rules).

- The largest subordinate clause has the conjunction that as its head. Don't forget, though, that that is not always a conjunction, even if it seemingly introduces a subordinate clause: it can also be the subject, as in the boy that gave Katniss the dandelion, where that is the subject of the relative clause (TP) modifying the noun boy.

- Interestingly, CPs with that as their head can have their head omitted, basically turning headless. You can say, 'Little did I know that I would grow up to become the very thing that I thought that I'd never be', sure. It's just that it sounds a bit clumsy, so we choose to omit the last two Cs (that's what the 0 is there for).

- Since the main C=inv, the sentence structure is inverted, meaning, the adjunct of V, the Adv little, moves to the specifier of the CP, while T moves to C=inv, as in questions, transforming from -pst to did.

Of course, that is not the only subordinating conjunction. You can also make sentences like

Ok, so now we have gotten to the level of the whole sentence but we still have

A few more considerations

Equal parts of a sentence

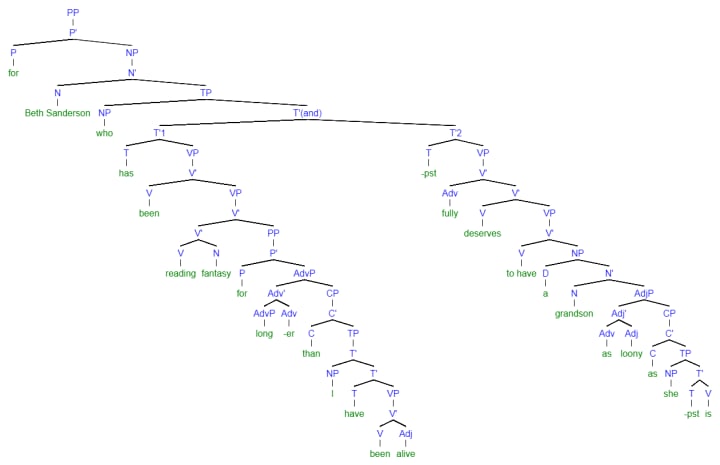

The book dedication of Brandon Sanderson's The Final Empire (a must-read if you're into epic fantasy) reads, FOR BETH SANDERSON, who’s been reading fantasy for longer than I’ve been alive and fully deserves to have a grandson as loony as she is.

So how do we draw this?

First of all, the whole sentence is actually a PP. The head of its NP complement is modified by a relative subordinate clause, meaning, a TP complement, in this case introduced by the relative pronoun who, which serves as the subject of the clause. As for the predicative, there are actually two. Two verbs, has (contracted to 's) and deserves, both are inflected, agree with the subject in person, and form a unit with it. That makes two equal tense head-complement complexes.

Equal parts of a sentence are parallel linguistic structures that serve the same role in the sentence and have identical relationships with every other member of the sentence. They can be either whole phrases or constituents such as heads, head-complement structures, or specifiers, unless the rules of the specific language pertaining to the specific phrase prohibit it, for example, in English, you can't say *the and an apple (makes no sense, does it?). Equal parts of a sentence are usually connected with a coordinating conjunction, which provides flow and context regarding the connection between the structures, as opposed to subordinating conjunctions that serve as heads of subordinate CPs.

Negation

It seems that there is no clear consensus about how negation works. Some treat it as a separate phrase (NegP) with not as its head and the negated phrase as its complement, which works very neatly for me in German but may not be linguistically accurate, as whether a certain phrase can take on a complement of another phrase should depend on the phrase type, not its modifiers. What I mean is, you could argue the idea that a TP can have either a VP or a NegP complement sounds wacky; rather, a TP takes on a VP that can be either affirmative (do sth) or negative (not do sth). Thus, some believe that negation may be another kind of specifier or some more abstract quality of the negated phrase.

For now, you can do your own little research and tinkering to figure out what system works for you. Meanwhile, I've downloaded a doctoral dissertation on negation and a whole book to deepen my knowledge of generative grammar, so I'll write an article once I get a clear idea of this aspect.

A few final tips

How to figure out the type of the phrase:

- look at the complements and specifiers (certain phrases have certain relations with other phrases);

- look up the part of speech of a word in a dictionary (remember that words can have multiple meanings, though);

- play with phrase tests such as substitution with a pro-word (like it for NPs and do for VPs) and playing with the word order (units move as units and will not let anything come between them).

Above everything, you must approach languages (or any kind of learning for that matter) with the scientific method. Experiment. Make hypotheses. Test them against new and different examples and improve your theory. Compare it with what others have done. Be willing to reconsider your previous assumptions. Think for yourself. Focus on structure always.

If you're learning this theory for practical purposes only, then don't worry about creating an unorthodox theory, as long as it makes sense and serves you well. What matters is that you find a system that allows you to understand, not just memorize, grammar. Now, instead of struggling with remembering which word order or form of a word you should use in which case, with a little bit of easy detective work, you'll see that in many of those cases, the same process actually happens, and much of it is, in fact, universal.

Hope this helps with your language learning goals! Questions and feedback are welcome and highly appreciated. Cactuses🌵 are, too, 💜 if you think this stuff is worth one. And if you'd like to go over a grammar topic with me, we can hop on a friendly Zoom call and try to figure it out together.

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments (1)

Well damn, deconvolving grammar into graphs and trees makes things much much easier, absolutely! Though, me heathen always believed that grammar is all about intuition and logic. But probably behind that logic the trees were hiding all along, sneaky koki. I'll try to return to your article some time when I have a fresh brain. Meanwhile, I have a question regarding zirgs list: does the "..." stay for all the remaining permutations, and all the 24 sentences make sense? Do they mean the same thing or have 24 different multihorseverse meanings?