Closing Time

Why does the end of the semester always bring out the best and the worst in students? Things are indeed "different" today and that is why we need to be "different" as faculty in response to changing times.

Ah, the end of the semester! As a "seasoned" professor with over 25 years experience working in the higher education industrial complex, this is always the busiest, most hectic, most stressful time of the year—both for college students and for their instructors. Though I'm far removed from that scene personally, I always like to draw the comparison to closing time at the bar....bringing to mind some wisdom from the classic song, "Closing Time," that is now—wow!—two decades old from the group, Semisonic:

Time for you to go back to the places you will be from....Every new beginning comes from some other beginning's end.

Yes, as a colleague of mine writes every few months on Facebook when the end of each semester rolls around, "the air is thick with desperation" among many students come each December, May, and late July-early August (and even more frequently if your school operates on the quarter system). Whether we are talking about the hallways of a state school or an elite private university, a directional school or a top research university, or even at a local community college, the end of the semester—the academic version of closing time—forces decisions to be made. Pass or fail? A, B, C...or worse.

Some students—really the majority of students—are rational about all of this. They know where they stand in a class, for the most part, so long as their professors do what they should do—establish a formal grading framework, stick to it, and update grades as they can during the course of the semester. If instructors follow these guidelines, most students know, and even accept their fate in a class. Of course, they are exponentially happier if this means they get an "A" versus "earning" a "D" (although there are some instances where a "D" is very welcome as opposed to the next letter on the scale!).

Now I do have colleagues—both at my own school and indeed at schools across the country...who shall go unnamed, where grading for them is indeed a mystery. How do they determine grades? There may really be no rhyme, no reason, no formula. Even in 2018, there are indeed instances where a professor issues a grade that is simply based on whatever. For all that we focus on the syllabus as a contract between the professor and his or her students—grades do sometimes do just "fall from the sky" or "are pulled out of one's butt!" They can be awarded (i.e. given) out of any human emotion—anger, love, mercy, pity...whatever. And so for all that we focus today on automating the grade process—and more and more things—including essays and papers—can be machine graded today with AI, there still comes a time when the professor has to input a grade into the system—and students know —and often they think, they hope,...and indeed, some do pray—that they will somehow "win" the lotto and get a better grade than they really deserve.

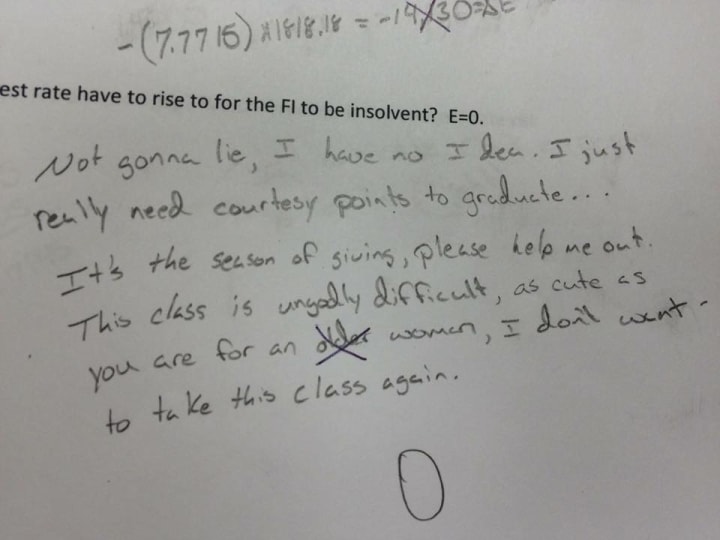

Now the lengths that students will go to in this regard is.... shall we say, amazing. Beyond the fact that finals are a very dangerous time for grandmothers in particular, today, there are endless ways to be creative. I have fellow professors who make it their jobs to go all "CSI" on every student note from a doctor as to whether or not it is legit or an elaborate criminal scam. Still, there's the old fashioned "begging" for points. I do get a few emails in this regard every semester—mostly asking, and mostly nicely—for things like if I could round their grade up, do "something" for extra credit, or if I would take into consideration some hardship they have had, allegedly. I have colleagues that more or less celebrate this tradition of academic life. Indeed, some have their personal "end of the semester" social media traditions in this regard, posting their personal "faves" of student "asks." From the not too effective, "I should have taken that Dale Carnegie course," approach with a note to the professor on a finance final...

...to my colleague who has the blanket, "Dr. No" style retort for all students, let's just say there is some fun, some might even argue too much fun—happening in the hallways at the end of the semester!

And so all of this brings to mind the latest video put together by a particularly talented, and vocal, colleague of mine at the unnamed "U" for which we both work. Dr. Joe Burns, a communications professor, is one of our faculty stars, kind of the local "King of All Media" (just not "Howard Stern-like" in any way, other that having the deep voice that is great for radio and doing voiceover work!). So Joe has put together a new video series in which he does for the masses what most of my colleagues love to do with students—pontificate. In the aptly titled series, "Is This Going to be on the Test"—which I urge your to seek out on his YouTube channel, Dr. Burns shares the lessons of experience that all of us in academia have and relates them as they apply as he sees them, both in college and in the bigger game that is life.

Dr. Burns' latest video entitled "Extra Credit," deals specifically with the end of the semester. Now I could make life easier on myself if I just set-up my laptop on a table in front of my office door and had this video playing on an endless loop three times a year, as basically, Joe says what many of us faculty would like to say in response to the student "inquiries" shall we say that invariably come at the end of each academic semester. You want "bonus points?" You want to turn-in something late—perhaps very late? You want partial credit? "You want fries with that A?" (well, not that last one...). Joe deals with them all with his simultaneous sense of humor and "tough love" sternness. And trust me, I do appreciate what he is saying, as we both have almost the same 25 plus years of experience in dealing with the same student issues each semester.

Here though, I'm going to make a sharp distinction where Dr. Burns sees a correlation. Where he sees college as a microcosm of the situations one will face in life out in the "real world," I take a different attitude now. Indeed, my attitude today toward students is far different from when I gave-up my corporate American Express card and the "all meals paid" lifestyle to go back to graduate school and get involved in all of this in the late 1980's. I don't think I'm jaded. Indeed, I think I'm a tad enlightened about all of this. Often, there's no absolute rule book, written or unwritten, upon which we can, or should, rely in such situations. I have come to to think that here's no right or wrong answer in dealing with a student's end of the semester inquiry. There's no black and white. And that's because things are indeed different, very different, for the students of today than when we walked uphill through the snow to college "back in the day."

Life has gotten, shall we say, way more complicated for the students of today. Family life today, indeed all of life today, isn't what is was in the 70's, 80's and 90's—the formative years for most of us today whose job title contains some combination of the words "college" and either "professor" or "instructor." We grew up with more intact families. We grew up with a more stable and accessible middle class. We grew up with the notion of a career path only going forward and up. We grew up when a set of encyclopedias in a classroom, or if we were lucky enough, in our own homes had some answers. We did not grow up with the luxury and curse of having answers to everything one search away on a device we carry in the palm of our hands at almost all times. We did not grow up with as many vices—from drugs to violence to gambling to "nudity on demand" to payday loans to a hundred other things and temptations—as are the reality of growing up today. We also went to college largely with folks like ourselves—who mostly looked like us, had mostly families like us, and had financial situations such as our own where we were lucky enough to not have to pay for all, or much, of our own schooling—or take out loans to pay for it.

In short, our college experience was far more homogenous—and —than that experienced by the students of today, and so were the people with whom we shared that experience. Yes, we may talk about having to do research in an actual library and go to a lab to actually be able to work on a computer. We attended college in an era where the law looked upon colleges as an extension of the home—in loco parentis means exactly what you think it does. We did not learn in an environment where litigation prevention and public relations was at the forefront of institutional concerns—for good and for bad. Diversity, #MeToo, fairness, reasonable accommodation—all of these have made the university environment of today better—and yet more complex—than it was "back in our day."

I used to have a "go to" saying back in the day that I thought was calligraphy-worthy that I would lay on students. This was: "Well, in college, at least you know when the tests are going to be...." Yes, in life, we never quite know, from month to month, from week to week, even from hour-to-hour when our important tests are coming. On the job, in our personal life, in our finances, with our families, indeed, even with our pets, we never know when we will get that phone call, that message, that email, that memo, that "Hey, can I see you in here for a minute, and why don't you go ahead and close the door behind you..." moments. Life has a way of throwing those things at you maybe not at the best of times, and maybe not when you are ready for them. Sometimes, they even come in bunches. And sometimes, they come too fast and too furious for you—or anyone—to really be expected to handle.

My own life experiences have taught me this hard lesson from time to time, and it's not an easy thing to have happen to you—let alone go through. From family issues to job issues to the death of loved ones, life can be—shall we say—in a word—difficult.

And so that is why I do less and less pontificating these days. I no longer look upon my own role as the dispenser of all wisdom with all the answers to life's questions - delivered with authority akin to the famous Egyptian Pharaoh of Yul Brenner in "The Ten Commandments."

Life is hard. Life is nuanced. And believe it or not, even though I carry an AARP-card in my wallet, I will admit that I am still learning life lessons myself—and often the hard way—and sometimes even the mistaken way. I do a lot more listening to students and try to ascertain what they are really saying and thinking these days. Quite often, a class problem is not a class problem—it is is merely the symptom of a problem that stems from a test they are facing that is far, far more real than any test they might have in my class or in any college class—dealing with domestic violence, dealing with the loss of a friend or relative to a drunk driver or to addiction, dealing with a pregnancy test that turned the wrong color, dealing with a long-term illness of a parent or partner, dealing with bills that they can't pay and even dealing with their own homelessness—or perhaps a home they can't go back to out of fear.

I can't pretend, let alone could I begin to think, that I have the answers for students with very real, very pressing issues like these. Indeed, I myself have more questions than answers, as most of us really do. I have to admit, that after what I've been through and continue to go through, most of my own life's challenges—safe from my father's long fight against Alzheimer's which inevitably ended about a year ago are small and trivial compared to what some 20-year-olds face today.

And thus, I can't begin to think that it is somehow in my job description to dispense life lessons. That's not what I signed-up for, and today, that's not my role—and I don't think that it should be any professor's role. Life has its own way of teaching you lessons. I don't think we should be piling on students who may be having very real issues. If you're dealing with life and death issues, trying to keep your family intact, or fighting against the demons of addiction—that's enough of life lessons for any of us. If we are naive enough to think that giving a student a bad grade on a paper because it was a day late or not allowing them to make-up a test because we didn't think the student's reason was "good enough" will teach them a lesson that they'll never be able to forget, well, we are inflating our own importance greatly in our own minds. And to what end are we doing this? The reason may have much more to do perhaps with our own ego (which in the professor ranks, there can be some egos!) than in caring for the real—sometimes very real—needs of our students.

Thank goodness most universities—including my own —have great resources available for students who need assistance with their own physical—and today even more—their mental health. I have had exactly zero hours of counseling training in my life. Yet more and more, student issues about a missed test, a late project, or excessive absences stem from very real causes with which I have absolutely, positively no personal experience! Fortunately, with one call or email (or yes, filling out an online form), we can put students in touch with mental health professionals and counselors who can do far more for them than we can with the "tough love" approach many of my colleagues take at times when students need - legitimately, a hand-up, not a life lesson from a professor.

And so yes, don't tell my students (Shhhhh!), but I'm far more likely today than I was five years ago, a decade ago, let alone when I started working with college students, to give them the "benefit of the doubt" and to try and work out a solution to their issues (and if I can't, put them in touch with someone on campus charged with helping them, and having the training to do so). It's called being human. And yes, we're in the business of helping make humans better, that is what college is supposed to be about. Students don't always get things right. They may ask for favors and "courtesy points" too often. Indeed, there are serial offenders that have 3, 4, 5... grandmothers die during their college years. However, I find that listening is far more effective than talking these days. And if we are in the "student success" business, it is up to those of us to work with students to a "roll with the changes." That does not mean giving grades away or being expected to bend over backwards for students. It simply means realizing a simple fact: that is the reality that life itself is the real test. Once we realize that simple fact—and the fact that we all have to continue to learn and to evolve ourselves, we in college faculty positions can—and must—do better for the students of today.

Now, back to all that $#%^ing grading and email I need to catch-up on here at the end of another semester—and yes, there will be emails...

About the Creator

David Wyld

Professor, Consultant, Doer. Founder/Publisher of The IDEA Publishing (http://www.theideapublishing.com/) & Modern Business Press (http://www.modernbusinesspress.com)

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.