The “Death House Landlady” Serial Killer

Dorothea Puentes murdered between 9 and 15 people for personal gain

When Trudy Mae and Jesse James Gray welcomed their daughter, Dorothea Helen Gray, into the world, I doubt they could have ever imagined that she’d grow up to be a notorious serial killer. Of course, it might very well be their poor child-rearing skills that led her down that path. Both parents were alcoholics, and Dorothea’s father made a habit of threatening to kill himself in front of the children.

Instead, Jesse Gray died of tuberculosis when Dorothea was only 8 years old, leaving behind a wife incapable of caring for her children. She lost custody of all her children the year after her husband died. The year after that, she was killed in a motorcycle crash. The children were left in the care of an orphanage where Dorothea claims she was sexually abused.

In 1945, 16-year-old Dorothea married Fred McFaul, a soldier who had just returned from World War II. Their two daughters were born in 1946 and 1948. It would seem Dorothea had no taste for motherhood. Her firstborn was sent to Sacramento to live with other family members and her secondborn was put up for adoption. A third pregnancy resulted in a miscarriage, after which her husband left her.

That same year, Dorothea was caught forging checks in Riverside. She pleaded guilty to two counts of forgery and was sentenced to four months in jail plus three years’ probation. Less than six months after being released, she moved from Riverside to San Francisco. There, she reinvented herself as “Teya Singoalla Neyaarda.” She claimed to be a Muslim of Egyptian and Israeli heritage. Under this guise, she met and married Axel Bren Johansson, a merchant seaman based in San Francisco. It was a doomed marriage. Dorothea filled her time during her husband’s trips to the sea by bringing lovers into their home or gambling heavily with his money.

By 1960, Dorothea was once more in trouble with the law. The bookkeeping firm she had opened in Sacramento was found to be a front for a house of ill repute. She was arrested for owning and running a brothel. A court found her guilty of the charges and sentenced her to 90 days in jail. Johansson had her committed to DeWitt State Hospital in 1961 after her drinking, deceitfulness, criminality, and failed suicide attempts got to be too much for him. The doctors found that she was a pathological liar and possessed an unstable personality.

Johannson finally divorced Dorothea in 1966 but she continued to use his last name and adopted the first name of “Sharon” to distance herself from her past. She presented herself to the community around her as a thoughtful Christian determined to establish herself as a caregiver to young women in the community who might need a helping hand. She provided them with a safe place to go to escape homelessness or abuse and did so without charge.

By 1968, Dorothea was once again married. This time to Roberto Jose Puente. The marriage was short-lived, ending after less than a year and a half. Though the couple separated, Puente returned to Mexico before she could serve him with divorce papers. She would not secure a divorce decree until 1973.

After the failure of her latest marriage, Dorothea focused her energy on the boarding house she continued to run in Sacramento. For a time, she served as a valuable resource that aided those struggling with alcoholism, homelessness, and mental illness. She held AA meetings and helped those who needed it to obtain their social security benefits or whatever other aid was available to them.

The Dorothea of old seemed to have evolved. Her appearance was now that of an older woman with graying hair who could be trusted and respected. She wore modest clothing and large glasses. She became heavily involved in the local Hispanic community, charities, scholarships, and radio programs. She soon met and married Pedro Angel Montalvo, but this was her shortest marriage yet. It lasted only a week before Montalvo suddenly left.

As it turned out, Dorothea hadn’t changed much at all. In 1978, she was arrested and convicted of illegally cashing thirty-four state and federal checks belonging to her tenants. She was given a very lenient sentence of five years’ probation and ordered to pay restitution of $4,000 but that was only the tip of what police would eventually find Dorothea had many more victims.

Ruth Monroe began living with Dorothea in an upstairs apartment in April 1982. Not long afterward, she died from an overdose of codeine and aspirin. The death was reported as a suicide after police were told Ruth had been depressed over her husband’s terminal illness and taken her own life.

74-year-old Malcolm McKenzie called police a few weeks later to accuse Dorothea of drugging and stealing from him. In 1982, she was sentenced to five years in prison for three counts of theft.

Everson Gillmouth began exchanging letters with Dorothea while she was in prison. When she was released after serving only three years of her sentence, Gillmouth picked her up outside the gates in a red 1980 Ford pickup truck. From there, they quickly went from pen pals to planning their wedding.

Later that same year, Dorothea sold the red pickup to Ismael Florez in exchange for his help in hanging some paneling in her apartment and $800 cash. She told him her boyfriend was in Los Angeles and didn’t need the truck anymore. She also asked him to build a large wooden box in which to store books and such. After he had completed the 6x3x2 foot box and left it for her to fill, she asked him to help her move the now sealed box into storage, but on the way there she instead told him to stop at a local dump used by locals.

On New Year’s Day, 1986, a fisherman came across the box and reported it to police as suspicious. Investigators opened the box to find human remains inside, but they were unidentifiable. Investigators opened the box and found the badly decomposed remains of a man inside. It would be three more years before he was identified. During that time, Dorothea stayed connected via letters with his family, telling them he was ill and that is why he was out of touch. She continued to run the boarding house and collect his pension check.

Dorothea’s boarding house was popular with social workers because she was one of the few that would accept the drug addicts and abusive tenants they found hard to place. She also continued to house many elderly tenants. She would routinely collect the tenants’ mail and pay them a stipend from any checks they received, pocketing the rest as the cost of providing for them.

Even though a condition of her parole was that she was not to have contact with the elderly or handle any government checks they might receive, probation officers made no note that she violated these terms over a course of fifteen separate visits from various agents of the court.

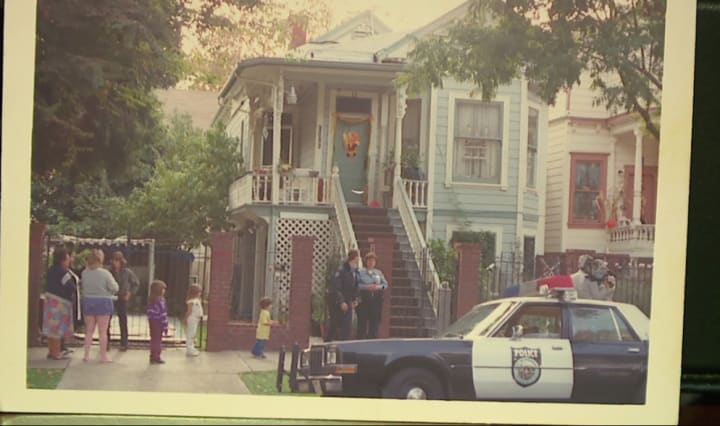

Dorothea found herself once again at odds with law enforcement on November 11, 1988, when they came to inquire about her tenant, Alberto Montoya. A social worker had reported Montoya, a developmentally disabled man with schizophrenia, as missing.

While at the property to inquire about his whereabouts, officers noticed displaced soil and decided to investigate it further. They unearthed the body of Leona Carpenter, who had been a tenant at the boarding house. Eventually, more bodies were recovered from the property.

Dorothea was charged with the murder of 77-year-old Everson Gillmouth and eight of her boarding house tenants:

· 61-year-old Ruth Monroe

· 78-year-old Leona Carpenter

· 51-year-old Alavaro “Alberto” Gonzales Montoya

· 64-year-old Dorothy Miller

· 55-year-old Benjamin Fink

· 62-year-old James Gallop

· 64-year-old Vera Faye Martin

· 78-year-old Betty Palmer

At first, police didn’t finger Dorothea as a suspect. They allowed her to leave the property to buy a cup of coffee nearby while they conducted their investigation of the property and interviewed any potential witnesses. Instead, she fled, heading to Los Angeles. There, she met a retired gentleman in a bar and sparked up a conversation with him. She was unaware that the man knew who she was from news reports he’d seen. He contacted law enforcement and Dorothea was arrested.

Due to the widespread media coverage of the murders, Dorothea’s lawyers, Kevin Clymo and Peter Vlautin III, filed a motion for a change in venue. It was granted and the trial was moved to Monterey County where it was prosecuted by John O’Mara of the Sacramento County District Attorney’s office.

O’Mara argued that Dorothea had used sleeping pills to render her victims unconscious, suffocated them, and hired convicts to dig the holes in her yard where they were buried. He called more than 130 witnesses to the stand during the year-long trial.

After all evidence was presented, the jury deliberated for more than a month before finally finding Dorothea guilty of three murders. The extended deliberations were due to an 11 to 1 deadlock for conviction on all counts. The holdout that was keeping the verdict stalled finally agreed to convict on two counts of first-degree murder with special circumstances and one count of second-degree murder. The remaining six counts were declared a mistrial.

In the penalty phase of Dorothea’s trial, the defense called witnesses to testify that their client was generous and caring. Even her long-abandoned daughter testified that her mother had been helpful in her youth and encouraged her to pursue a successful career.

Mental health experts were also brought in to give testimony about Dorothea’s abusive childhood and discuss how that had led her to help the less fortunate. The experts also said that she did have a darker side brought on by the stress of running a boarding house full of tenants such as those she took on.

In his closing statement, the prosecutor focused on the murders, arguing that Dorothea was responsible for her conduct and that her victims were human beings who had the right to live. He pointed out that she had taken the only possessions they had, their money and their lives. He advocated for the death penalty.

The defense avoided further discussion of the murders and focused on Dorothea’s qualities as a caregiver and her history of abuse. He asked them to put themselves in her shoes and try to picture how they might have coped in similar circumstances. He contended that it was her good qualities that had brought so many to court to testify as to her good character and suggested that her life was worth preserving. He advocated for life in prison without parole rather than capital punishment.

In the end, she was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole and incarcerated at Central California Women’s Facility. She continued to insist that she was innocent and all of her boarders had died of natural causes.

Dorothea died in prison on March 27, 2011. She was 82 years old.

About the Creator

A.W. Naves

Writer. Author. Alabamian.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.