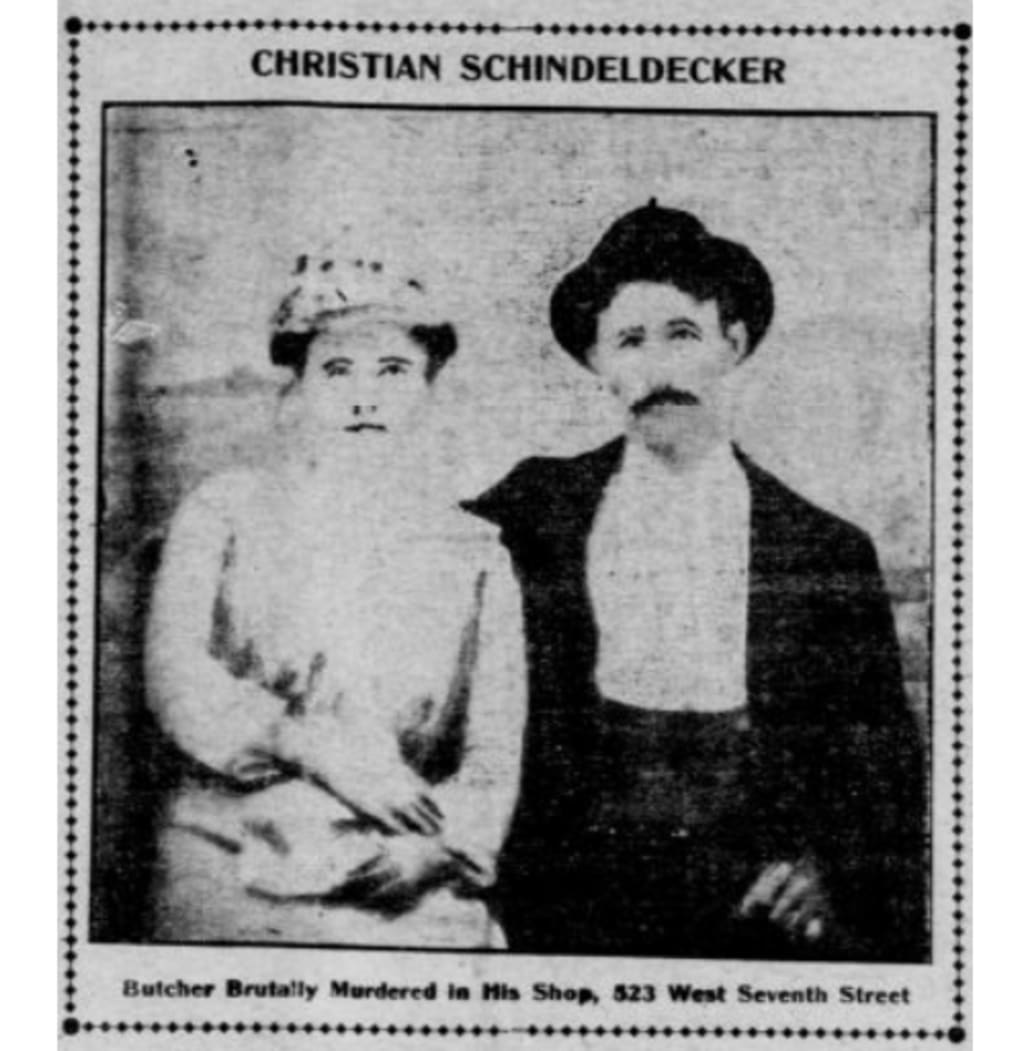

The 1905 Murder of Butcher Christian H. Schindeldecker

One of the most brutal crimes in St. Paul history

One of St. Paul's most brutal and cold-blooded crimes occurred in a downtown butcher shop shortly after noon on February 18, 1905.

At 12:05 PM, seventeen-year-old Walter Gerenz, delivery boy for Christian Schindeldecker's butcher shop at 523 West 7th St., walked home for lunch. He returned forty minutes later to find the shop's front door bolted shut. Assuming his boss had stepped out, Gerenz went around back to enter.

Seconds after walking in, he found Schindeldecker lying on the floor. The thirty-three-year-old butcher was dead. Gerenz ran to get help.

During their investigation, police noticed the front door was nailed shut. They also discovered the butcher's pocketbook and the store's cash box were empty. Among the items found at the scene were a couple of broken eggs, a bloodied cleaver, and a tinsmith's hammer with the initials "CH" on it.

Schindeldecker had been struck with the hammer and cut thirty-two times with the meat cleaver.

Police believed the killer entered to buy eggs. When Schindeldecker turned to grab them, they hit him in the head with the blunt end of the hammer. The butcher dropped to the floor, unconscious.

With Schindeldecker incapacitated, his attacker went to the shop's front door and nailed it shut. Then, he dragged the butcher into a rear room. After taking money out of the cash box, the attacker rummaged through Schindeldecker's pockets. The butcher regained consciousness while being robbed. He was groggy and out-of-sorts but awake.

Afraid of being recognized, the killer grabbed the closest thing he could find—a meat cleaver—and attacked Schindeldecker, killing him. The man then escaped through the back door.

A city-wide investigation soon led authorities to Edward Gottschalk, also known as Ed Moeller, Ed Mueller, or Charlie Carter. While searching his room, which was only a few blocks from the crime scene, they found a tinsmith's hammer, pristine-looking copper pennies, and overalls covered with blood-colored stains.

Gottschalk was arrested.

However, any evidence the police had was circumstantial, and Gottschalk knew it. He refused to give them any information they could use. Gottschalk didn't admit to the charges against him, but he didn't explain them away either.

After local newspapers reported the arrest, several witnesses came forward. Gottschalk was seen casing the butcher shop in the days before the robbery. On February 18, less than an hour before the murder, he was seen reading at a barbershop across the street from the crime scene. Each witness remembered seeing Gottschalk with a younger man. Police considered the unknown person an accomplice.

The second attacker's name came from the hammer found at the crime scene. Charles Hartmann went to the police to report that "CH" stood for Charles Hartmann Jr., his son. The hammer belonged to him. According to witnesses, Joseph, Mr. Hartmann's other son, matched the description of Gottschalk's companion.

Authorities searched the city, but Joseph Hartmann couldn't be found. Hartmann's father was sure Gottschalk had killed his son. Officials disagreed. They assumed he was running from the crime and increased their dragnet – sending his description to police stations throughout the Midwest.

Meanwhile, Gottschalk was not endearing himself to the local police. From the beginning, he'd given authorities nothing of substance and remained loud, disagreeable, and quick to temper throughout. Gottschalk constantly complained, even secretly writing a letter detailing his poor treatment and pushing it through his prison window to the outside world.

The letter was found by two boys and printed in the local newspaper. However, nothing came of the complaints. Police saw them as little more than the rantings of a soon-to-be condemned man.

Suddenly, Gottschalk got chatty. He discussed his case with anyone who visited. According to him, the media had wrongly accused him of the crime, and the police were out to get him. Gottschalk looked forward to being vindicated. Also, almost reluctantly, he began blaming Hartmann for Schindeldecker's death. Gottschalk thought he was a likable young man but had trouble controlling his temper.

On March 16, investigators discovered Hartmann's body downstream from Pickerel Lake. Iron weights were attached to his feet to keep him submerged. Immediately, police believed Gottschalk had murdered him. The pressure of the crime likely made the young man do strange things, and Gottschalk probably thought he would implicate him in the murder.

That same day, Gottschalk was bound over to the grand jury.

Authorities believed Hartmann was only a tool. He was an accessory to the robbery but had no clue Schindeldecker would be killed. They charged Gottschalk with a second murder. He pleaded not guilty to both.

Gottschalk remained unflappable. The walls were closing in around him, but he still got a good night's sleep.

As the trial neared, circumstantial evidence depicted a guilty man. On May 8, 1905, Gottschalk pled guilty to murdering Hartmann, but claimed it was self-defense.

When he and Gottschalk went fishing the Monday after the murder, Hartmann used a razor blade to file his fingernails. Gottschalk believed he'd be murdered with the weapon, so he killed Hartmann first. He then dumped the body into a hole on the frozen lake.

Concerning Schindeldecker's death, Gottschalk's story was decidedly different from the one the police told. In court, he testified Hartmann was the aggressor. Gottschalk waited outside the shop as a lookout, and was shocked when the young man came out dripping in blood. He panicked and left with Hartmann to get him cleaned up.

There was a method to his madness. In early twentieth-century Minnesota, first-degree murder was a capital crime unless the judge found extenuating circumstances. By throwing himself upon the mercy of the court, Gottschalk hoped for life in prison instead of a trip to the gallows.

It didn't work. On May 12, 1905, the judge sentenced him to death for Hartmann's murder. Soon after, local papers published Gottschalk's written confession for his role in the murders of both Hartmann and Christian Schindeldecker.

Days later, the governor named August 8 the date of Gottschalk's hanging.

The convicted man had other plans. Shortly before 2:00 PM on July 19, 1905, Edward Gottschalk tore a section of his bed sheet and tied it to the ceiling. He then hung himself.

The murder of Christian H. Schindeldecker, while narrowed to either Gottschalk or Hartmann — or both, was never solved.

Sources

- The Minneapolis journal. "Confesses to Brutal Murder." May 8, 1905, 1. https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn83045366/1905-05-08/ed-1/seq-1.

- The Minneapolis tribune. "Confession." July 21, 1905, 7. https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn83016771/1905-07-21/ed-1/seq-7.

- The Minneapolis tribune. "Gallows." July 20, 1905, 1. https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn83016771/1905-07-20/ed-1/seq-1.

- The Minneapolis tribune. "Sentenced to Hang by Neck Until Dead." May 12, 1905, 11. https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn83016771/1905-05-12/ed-1/seq-11.

- The Post and record (Rochester). "Gottschalk Says Guilty." May 12, 1905, 11. https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn90060314/1905-05-12/ed-1/seq-12.

- The Saint Paul globe. "Father of Hartmann Believes Gottschalk Killed His Son." March 1, 1905, 2. https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn90059523/1905-03-01/ed-1/seq-2.

- The Saint Paul globe. "Gottschalk Faces Seven Accusers." March 15, 1905, 5. https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn90059523/1905-03-15/ed-1/seq-6.

- The Saint Paul globe. "Murder Mystery Baffles Police." February 20, 1905, 1. https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn90059523/1905-02-20/ed-1/seq-1.

- The Saint Paul globe. "Police Believe They Have the Slayer of Schindeldecker." February 26, 1905, 1. https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn90059523/1905-02-26/ed-1/seq-25.

- The Saint Paul globe. "Body of Hartmann is Found in the River." March 16, 1905, 1. https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn90059523/1905-03-18/ed-1/seq-1.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.