No. 5- Dr. Death

Seven of the Most Notorious Serial Killers in History

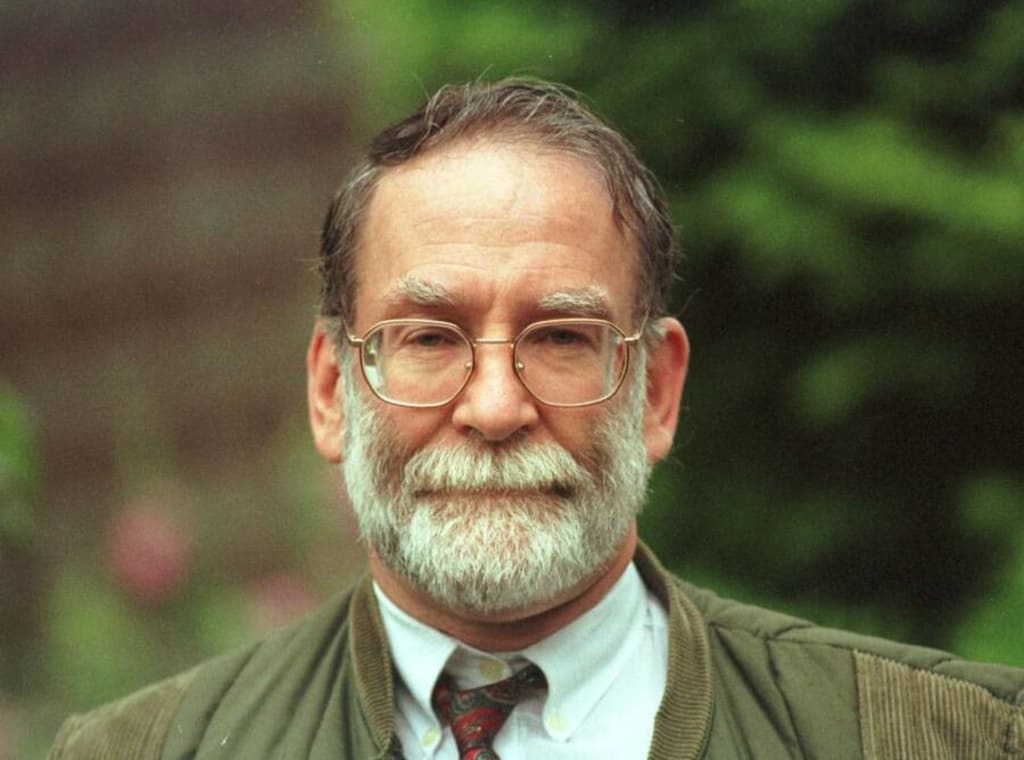

Fred Shipman, also known as Harold Frederick Shipman (14 January 1946 – 13 January 2004), was an English general practitioner and serial murderer. With an estimated 250 victims, he is regarded as one of the most prolific serial killers in contemporary history. Shipman was found guilty on January 31, 2000, of killing 15 patients who were under his care. He received a life sentence with a lifetime restriction. On January 13, 2004, at the age of 57, Shipman committed himself by hanging himself in his cell in HM Prison Wakefield in West Yorkshire.

Under the direction of Dame Janet Smith, a two-year inquiry of all deaths Shipman certified looked at the crimes committed by the man. It became clear that Shipman preyed on older individuals who were weak and believed him because he was their doctor. He either administered a lethal quantity of medication to his victims or prescribed an excessive amount.

Shipman, known by the monikers "Dr. Death" and "The Angel of Death," is the only British physician to have been found guilty of killing his patients to date; however, other physicians have been cleared of comparable crimes or found guilty of less serious offenses.

Family, Upbringing, and Education :

Shipman was the second of three children born to truck driver Harold Frederick Shipman (12 May 1914 – 5 January 1985) and Vera Brittan (23 December 1919 – 21 June 1963) on the Bestwood Estate, a council estate in Nottingham, on January 14, 1946. His poor parents were devoted Methodists. Shipman was a skilled rugby player in juvenile levels when he was younger.

After passing his eleven-plus exam in 1957, Shipman enrolled in High Pavement Grammar School in Nottingham, which he attended until 1964. He was a strong distance runner and served as the team's vice-captain in his last year of school. When Shipman was seventeen years old, his mother, who had been diagnosed with lung cancer, passed away.In the last stages of her illness, she had morphine supplied at home by a doctor, which eventually became Shipman's own method of operation. Despite having a terminal illness, Shipman saw his mother's pain ease up until her passing on June 21, 1963. He wed Primrose May Oxtoby on November 5th, 1966; they had four kids together.

Shipman completed his medical studies at the University of Leeds' Leeds School of Medicine in 1970.

Career :

In 1974, Shipman accepted his first post as a general practitioner (GP) at the Abraham Ormerod Medical Center in Todmorden. Shipman had previously worked at the Pontefract General Infirmary in Pontefract, West Riding of Yorkshire. The year after, Shipman was discovered fabricating pethidine prescriptions for his personal use. He paid a £600 fine and spent a short time in a York drug recovery facility. In 1977, he served as a general practitioner at Donneybrook Medical Center in Hyde, Greater Manchester.

Throughout the 1980s, Shipman continued to practice general practice in Hyde. In 1993, he opened his own office at 21 Market Street, where he quickly earned the respect of his neighbors. He was questioned about how the mentally ill should be handled in the society in an episode of the Granada Television current affairs documentary World in Action in 1983. The conversation was rerun on Tonight with Trevor McDonald a year after his conviction on murder charges.

Detection :

Concerned about the high mortality rate among Shipman's patients, Linda Reynolds of the Brooke Surgery in Hyde voiced her worries to John Pollard, the coroner for the South Manchester District, in March 1998. She was particularly worried about the enormous number of paperwork for old women's cremations that he had required countersignature on. Police ended the inquiry on April 17 after determining there was insufficient proof to file charges.Greater Manchester Police was eventually held accountable by the Shipman Inquiry for sending untrained officers to handle the case. Following the conclusion of the investigation, Shipman murdered three more people.

A few months later, in August, cabbie John Shaw reported to the police his suspicions that Shipman had killed 21 patients. Shaw started to wonder why so many of the elderly patients he brought to the hospital and who appeared to be in good health passed away while in Shipman's care.

Kathleen Grundy, a former mayor of Hyde, was Shipman's final victim. She was discovered dead at her house on June 24, 1998. He was the last person to see her alive, and he later put his signature on her death record, putting "old age" as the reason of death. When fellow attorney Brian Burgess told Grundy's daughter Angela Woodruff that a will had been drafted, ostensibly by her mother, with questions regarding its veracity, she grew anxious. Woodruff and her children were not mentioned in the bequest, but Shipman received £386,000. Woodruff went to the police at Burgess' prompting, and they launched an inquiry.

When Grundy's body was unearthed, it was discovered to have traces of heroin (heroin), a drug frequently used to treat the suffering of terminal cancer patients. However, a police examination of Shipman's computer revealed that the entries were made after Grundy had passed away. Shipman had claimed that Grundy had been an addict and had shown them comments he had written to that effect in his computerized medical journal.

When Shipman was apprehended on September 7, 1998, a Brother typewriter similar to the one used to create the fake will was discovered in his possession. According to the 2000 book Prescription for Murder by journalists Brian Whittle and Jean Ritchie, Shipman may have fabricated the will in order to avoid being discovered, because his life was out of control, or because he intended to retire at age 55 and flee the UK.

Police looked into further fatalities. Shipman examined and certified fifteen sample cases. He had a practice of giving diamorphine in deadly quantities, writing death certificates for individuals, and then forging their medical records to claim they had been unwell.David Spiegelhalter and colleagues stated in 2003 that "statistical monitoring could have led to an alarm being raised at the end of 1996, when there were 67 excess deaths in females aged over 65 years, compared with 119 by 1998."

Trial and imprisonment :

On October 5, 1999, Shipman's trial got under way at Preston Crown Court. He was accused of murdering 15 people between 1995 and 1998 by administering deadly doses of diamorphine:

- Marie West

- Irene Turner

- Lizzie Adams

- Jean Lilley

- Ivy Lomas

- Muriel Grimshaw

- Marie Quinn

- Kathleen Wagstaff

- Bianka Pomfret

- Norah Nuttall

- Pamela Hillier

- Maureen Ward

- Winifred Mellor

- Joan Melia

- Kathleen Grundy

Due to the alleged fabrication of Grundy's will, Shipman's legal counsel unsuccessfully sought to have the Grundy case tried separately from the others.

After six days of deliberation, on January 31, 2000, the jury declared Shipman guilty of 15 counts of murder and one count of forgery. Mr. Justice Forbes then sentenced Shipman to life in prison for each of the 15 murder charges against him, with the suggestion that he also serve a full life term concurrently with a four-year sentence for forging Grundy's will. The General Medical Council (GMC) removed Shipman from the medical registration on February 11, 11 days after his conviction.Just months before British government ministers lost their authority to set minimum terms for prisoners, Home Secretary David Blunkett confirmed the judge's whole life tariff two years after it was initially proposed. Authorities had the option of filing several additional charges, but they decided against it because of the extensive media coverage the first trial received. The 15 life sentences previously given out made more litigation pointless.While incarcerated, Shipman made friends with Peter Moore, a fellow serial killer.

Shipman contested the scientific evidence against him and disputed his guilt. He never expressed his opinions in the media. Even after his conviction, Shipman's wife, Primrose, remained adamant that he was innocent.

The only physician ever convicted of killing his patients in British history is Shipman. John Bodkin Adams was accused of killing one patient in 1957 despite rumors that he had killed many more over a ten-year period and "possibly served as Shipman's role model." He was found not guilty, and no more accusations were brought against him. According to historian Pamela Cullen, Adams' acquittal prevented the British legal system from being scrutinized until the Shipman case.

Death :

At the age of 57, Shipman hung himself in his cell at HM Prison Wakefield around 6:20 in the morning on January 13, 2004. At 8:10 a.m., he was pronounced dead. He hung himself from his cell's window bars using his bed clothes, according to a statement from Her Majesty's Prison Service. Shipman passed away, and his corpse was transported by undertaker's van to the morgue at the Medico Legal Centre in Sheffield for a post-mortem examination. The remains was finally returned to the family by West Yorkshire Coroner David Hinchliff after an inquiry was started and adjourned shortly after.

As a result of Shipman's death, several of the victims' relatives claimed they felt "cheated" since they would never have the pleasure of a confession or an explanation for why he did his atrocities. Home Secretary David Blunkett said that it was tempting to celebrate: "You wake up and you get a phone saying Shipman has overdosed, and you wonder, is it too early to crack open a bottle? Then you find out that everyone is furious with him for doing it.

National media were split over Shipman's death; the Daily Mirror called him a "cold coward" and criticized the Prison Service for allowing him to commit suicide. The Sun, on the other hand, printed the joyful front-page headline, "Ship Ship hooray!" The Independent demanded that the investigation into Shipman's suicide include a broad look at both the condition of UK prisons and the wellbeing of inmates.General Sir David Ramsbotham, who formerly held the position of Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Prisons, advocated for the replacement of whole-life sentences with indefinite ones in The Guardian. He claimed that doing so would at least give prisoners some hope of eventual release, lower the likelihood that they will commit suicide, and make managing them easier for prison staff.

Although Shipman reportedly told his probation officer that he was considering suicide to ensure his wife's financial security after he lost his National Health Service pension, the reason for his suicide was never determined. If Primrose Shipman had lived above the age of sixty, she would not have been eligible for a full NHS pension.In addition, there was proof that Primrose had started to doubt Shipman's culpability despite his long-standing protestations of innocence in the face of overwhelming evidence. Shipman was temporarily denied privileges, including the ability to call his wife, as a result of his refusal to participate in programs that would have pushed him to confess his crimes.According to Shipman's cellmate, at this time, Primrose wrote him a letter urging him to "Tell me everything, no matter what."Shipman's suicide "could not have been predicted or prevented," according to a 2005 investigation, but protocols should nevertheless be reviewed.

Despite several erroneous claims concerning Shipman's funeral, his remains was left in Sheffield for more than a year after being given to his family. Police warned his widow not to bury her husband in case his tomb was harmed. Shipman was ultimately cremated at Hutcliffe Wood Crematorium on March 19, 2005.Primrose and the couple's four children were the only ones present during the cremation, which was held at a time other than regular business hours to protect privacy.

Aftermath :

Chris Gregg, a senior West Yorkshire Police officer, was chosen to head an inquiry into 22 of the fatalities that occurred in West Yorkshire in January 2001.The Shipman Inquiry, which was completed in July 2002, came to the conclusion that between 1975 and 1998, when he was in practice in Todmorden (1974–1975) and Hyde (1977–1998), he had murdered at least 218 of his patients. The judge who provided the findings, Dame Janet Smith, acknowledged that many further unexplained fatalities could not be conclusively linked to Shipman. Most of his victims were healthy older women.

Smith stated in her sixth and final report, which was released on January 24, 2005, that she had strong suspicions about four additional deaths, including the death of a four-year-old girl, that occurred early in Shipman's medical career at Pontefract General Infirmary and that she believed he had killed three patients. Between 1971 and 1998, he was responsible for the deaths of 459 patients, although it is unclear how many of them were murder victims because he frequently served as the lone physician to certify a death. 250 victims were thought to have been Shipman's total throughout those 27 years, according to Smith.

The GMC accused six doctors of wrongdoing for signing cremation authorization papers for Shipman's victims when they should have seen the correlation between Shipman's home visits and his patients' fatalities. These physicians were all found not guilty. A comparable hearing was held in October 2005 against two physicians who were employed at Tameside General Hospital in 1994 and who were found not to have known that Shipman had purposefully delivered a "grossly excessive" quantity of morphine.The Shipman Inquiry suggested changing the GMC's organizational structure.

It was discovered in 2005 that Shipman could have taken jewelry from his victims. Police had discovered almost £10,000 worth of jewelry in his garage in 1998, which they had confiscated. When Primrose requested its return in March 2005, police sent letters to the families of Shipman's victims requesting that they identify the jewelry.The Assets Recovery Agency received unidentified objects in May.In August, the inquiry was finished. Authorities sold 33 items that Primrose verified weren't hers and returned 66 pieces to her. The auction's proceeds were donated to Tameside Victim Support.A platinum diamond ring with a photo of the family as ownership confirmation was the sole item given back to the family of a slain patient.

The Garden of Tranquility, a memorial garden for Shipman's victims, debuted on July 30, 2005, in Hyde Park, London.Over 200 families of the Shipman victims were still looking for financial compensation as of the beginning of 2009. Letters that Shipman wrote while incarcerated to pals were scheduled to be auctioned off in September 2009, but the sale was canceled after media and victim's family concerns.

Shipman effect :

The "Shipman effect"—a series of changes to accepted medical practices in the UK—was brought on by the Shipman case and a number of recommendations in the Shipman Inquiry report. Many doctors reported changes in their prescribing habits, and it's possible that a reluctance to take the chance of over-prescribing painkillers led to under-prescribing.Practices for death certification were also changed. The transition from single-doctor to multi-doctor general practices was arguably the biggest transformation.[Reference required] This was not a direct suggestion; rather, it was done because the study found that there was insufficient oversight and protection of physicians' judgments.

The questions on the forms required for cremations in England and Wales have changed as a direct result of the Shipman case. For instance, the individual or people organizing the burial must respond to the question, "Do you know or suspect that the deceased person's death was violent or unnatural? Do you think there needs to be any more investigation of the deceased person's remains?

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.