How Pablo Escobar Built His Own Private Army

He escaped, but it was the deadliest car bomb attack in Latin America at the time - and the most dramatic attack in a series that had killed dozens of Colombian politicians, government agents, and even journalists who crossed Escobar.

Supervillains have some pretty big perks. They build their massive lairs - maybe with a death laser or two. They even have a private army of henchmen. The stuff of comic books? Not quite. In the 20th century, one criminal took “filthy rich” to a whole other level.

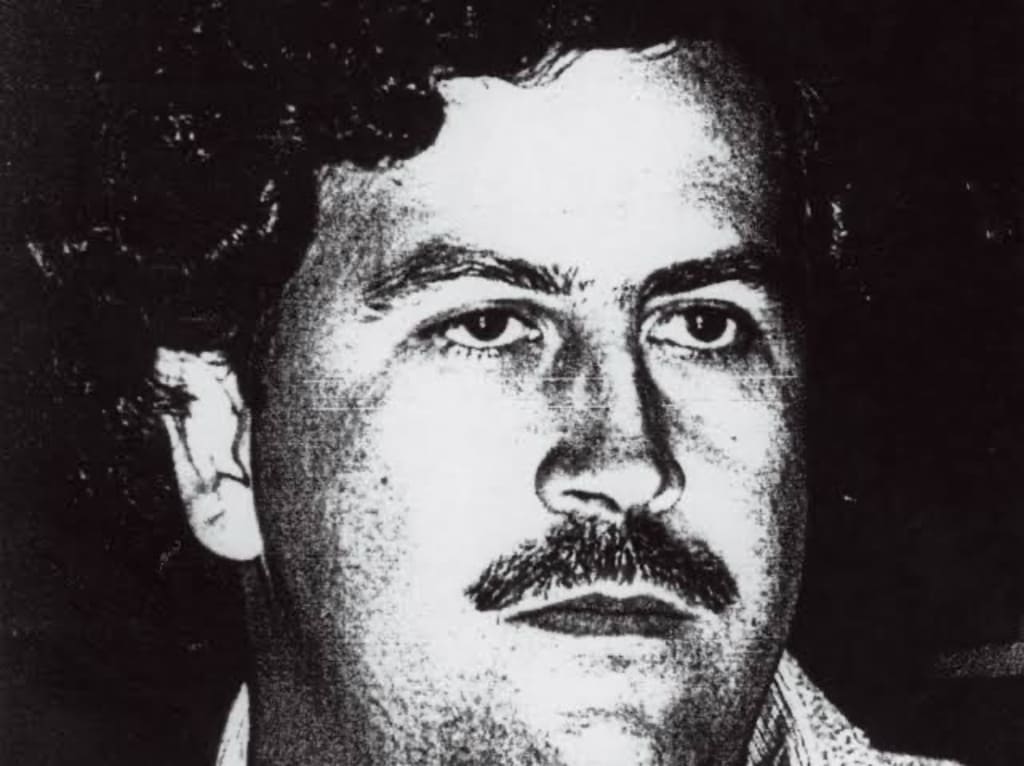

Colombian drug kingpin Pablo Escobar liked the finer things in life, but he knew he had a lot of enemies looking to take them - ranging from the government to rival criminals. So to protect everything he owned, he built one of the most powerful private armies of all time. But he didn’t start nearly as powerful. Escobar knew what it was like to start from nothing - and he was going to make sure he never went back. A college dropout from Medellin, he kicked off his criminal career in the 1960s by selling cigarettes and fake lottery tickets. Soon he gained a reputation as a talented criminal and was recruited by local drug smugglers. They didn’t trust him with the product at first, but he carried out other missions - particularly kidnapping enemies of the cartels or anyone who was in the wrong place at the wrong time and holding them for ransom.

It wouldn’t be long before he was on to bigger and better things. The year was 1976, and the drug trade was heating up and crossing borders. There was a massive market for powder cocaine in the United States, and Escobar founded one of the first cartels that focused on this demand. He gave it a hometown touch - calling it the Medellin Cartel - and it quickly started smuggling mass amounts of the drug across the border. Soon, they were smuggling up to eighty tons of the substance across the border every month, and that money came right back to Colombia. Soon, Escobar wasn’t a local boy turned criminal - he was one of the most wealthy people in the world. But more money, more problems.

As Escobar’s power grew, so did his enemies list. Politicians both inside and outside Colombia wanted to find the man behind the cartel - and other criminals wanted a piece of the action. As the battle for a place in the drug trade escalated, rival cartels did battle with Escobar’s team, and Colombia turned into the murder capital of the world. Escobar even tried to seize political power, being elected as an alternate member of the Chamber of Representatives. But his ambitions for legitimate control of the country were thwarted and many people still wanted to see him under arrest. But that was going to turn out to be very tricky. The 1980s were Escobar’s heyday, and he quickly put his billions to good use. He would soon build himself a massive mansion complete with an exotic zoo, a private airport, and a bullfighting ring among other amenities. It looked more like an amusement park than a criminal’s mansion, but many of his criminal associates probably asked the question - why would someone as wanted as Pablo Escobar build himself a mansion that made himself an even bigger target than he already was? The simple answer was that Pablo Escobar could protect himself. There had never been a cartel quite the size of the Medellin Cartel, and it soon grew from its base in Colombia to have outposts in most of South and Central America, the Caribbean, and major cities in the United States. But his base of power was in Colombia, and he had surrounded himself with an elite hit squad to target his competitors. As the government stepped up pressure against him and created an elite anti-narcotics force with a military background, he found many of his lieutenants were getting gunned down in the streets. And he was ready to fight back - with help from an unusual source. The first evidence of just how powerful Escobar had gotten came in 1985 when Colombia found itself under attack. But it wasn’t Medellin Cartel soldiers - the culprits were members of the M-19 guerilla group, laying siege to the Palace of Justice in Bogota. This Supreme Court building was the home of the highest law of the land, and the twenty-five judges were soon held hostage by leftist militants.

It was a well-organized assault, the most daring of any by the group so far. They killed three people as they charged into the building. While police were able to free many hostages, the Chief Justice and many of the judges were unable to escape. What would follow was one of the bloodiest days in Colombian memory. After negotiations on the second day broke down, the Colombian military launched a full-on assault on the Palace of Justice. This had terrible consequences, including the deaths of 98 people in total - many being hostages, including about half the Supreme Court justices. Beyond the human loss, the military’s assault destroyed six thousand documents that erased many of the criminal records kept at the building. The military was blamed by many for their over-aggressive moves, but soon people were looking at other possible causes. Had there been a hidden hand behind the M-19 group? It wasn’t long before the Justice Minister alleged that drug cartels - likely with Escobar involved - had planned the siege to eliminate the criminal records and terrorize the judiciary.

Shockingly, Escobar was not available for comment - although years later, his son would admit that Escobar had paid M-19 a million dollars to support their cause while denying direct involvement. This only caused scrutiny on the Medellin Cartel to increase, and Escobar’s team found itself under greater assault from the Colombian government. But he might have been one step ahead. During the 1980s, Escobar was building an army - but no one could see it. His team didn’t use fatigues and carry weapons out in the open. This was by design as Escobar wanted to strike fear into Colombia’s leadership through asymmetrical warfare - attacking their institutions anonymously and creating a sense of paranoia. If anyone could be working for the cartel and target the economy and leaders of the country, maybe the government would think twice about getting involved in Escobar’s business. But as the 1980s waned, Escobar would end up crossing the line. It was November 27th, 1989 when Avianca Flight 203 was taking off from Bogota to Cali.

The flight was a standard short-haul flight and the crew was all well-trained, but that wouldn’t protect the 107 people on board. Five minutes into the flight, just as it reached around 13,000 feet, a massive explosion rocked the cabin and ignited the central fuel tank. The plane was ripped apart, killing everyone on board as well as three people on the ground. A full investigation ensued, and it wasn’t long before evidence of plastic explosives was found. But the full story was even more shocking. Investigations showed the bomb had been carried onto the plane by two men who likely worked for Escobar, and one of them had escaped the plane before it took off. The actual target? Cesar Gaviria Trujillo, a prominent presidential candidate who many expected to win the election and crack down on Escobar. Unfortunately for the drug kingpin, Trujillo was not on board and went on to win handily - no doubt boosted by outrage over the bombing! Bringing down even more heat on Escobar, two Americans were on the plane - which meant that the first Bush administration was about to make tracking down the kingpin a priority.

So naturally, Escobar’s next move was to escalate - massively. The Administrative Department of Security building in Bogota was one of the government’s most important headquarters and the source of much of the intelligence behind the hunt for Escobar. And it was only eight days later, while Colombia was still reeling from the Avianca bombing when Escobar struck again. A truck was parked near the building, and just as the work day was beginning, a massive dynamite bomb was detonated, shattering the front of the building and destroying fourteen city blocks. In total sixty- three people were killed in Colombia’s biggest urban centre. More than three hundred businesses were destroyed in the bombing, and once again no one claimed responsibility. But the government pointed the finger squarely at Escobar’s organization - and the belief is that it was an attempt to assassinate the DAS director.

He escaped, but it was the deadliest car bomb attack in Latin America at the time - and the most dramatic attack in a series that had killed dozens of Colombian politicians, government agents, and even journalists who crossed Escobar. The ruthless crime lord had gone from being a drug lord to being a military powerhouse. And he was just getting started. Escobar was now the most wanted man in Colombia and one of the most hunted in the world. But as Colombian officials closed in, they discovered a problem - he was impossible to get to. Not only was he heavily guarded, but he had created an inner sanctum in his hometown of Medellin where the locals were fiercely loyal to him. How did a ruthless criminal create such loyalty? Because while Escobar was feared by his enemies, he had a very different approach to his hometown - a charm offensive.

He was using his drug money to turn the poor city into a paradise. Escobar was building football courts and housing complexes, and even sponsoring children’s sports teams. And that wasn’t the only way he was boosting his power. The drug business was booming, and many ambitious young dealers wanted to get into the business. But to do that, you would have to kiss the ring. Escobar was the biggest fish in the pond - especially in Colombia, but also where he had outposts around the hemisphere. Any ambitious dealer who went into business for themselves would risk angering one of his agents and finding themselves on the business end of a 12-gauge buyout. So for many, it was safer to do business with him instead. Traffickers would often turn over between a fifth and a third of their profits to Escobar since he was the one with the connections to get the shipments into the United States. It pays to be the king. Escobar was quickly building a complex network of supporters - most of whom were invisible. By basing his operations in Medellin, he was able to capitalize on the loyalty he built there and create a group of allies who would lie to the police about his location or even serve as lookouts to tip him off if needed.

He always seemed to be a step ahead of the authorities - and that’s because he was. Between his connections with the people, his connections with the rest of the underworld, and the people he successfully bribed in the government and the police force, Escobar always had enough intel to keep him ahead of the government. And this gave him the money and time he needed to take his private army from an invisible one - to one that was about to give the Colombian government hell. Because the war was about to heat up. Ironically, it would be Escobar’s greatest defeat that would lead him to his highest level of power. His nemesis Cesar Gaviria had taken control of the country, and the assassination of a prominent liberal politician in 1989 had stepped up the heat on Escobar.

The government took out many of his top lieutenants and eventually cornered him. Hoping to avoid a bloody war with the cartels, the Gaviria government agreed to a deal. Escobar would surrender to authorities with a guarantee that he wouldn’t be extradited to the United States. He would also get a reduced sentence which he could serve at the prison of his choice. And the prison he chose…was one he would build himself. Pablo Escobar was about to get the supervillain lair of his dreams. Sentenced to five years despite the massive trafficking business and all the murders - most of which couldn’t be proven - Escobar built himself the La Catedral prison, a mansion that had a football field, a bar, and even a jacuzzi and waterfall. Guards would be stationed in a tower to keep him from escaping, but otherwise, he would mostly be left to his own devices. In a thoroughly predictable move, it soon became his new base of operations, as the Medellin Cartel seemed mostly undeterred.

Somehow, the drug bosses all got their orders, which led authorities to believe that Escobar was running his empire from behind bars - and they soon decided the operation wasn’t working out. It was time for Escobar to go to a real prison. But he had other ideas. It was just over a year after his confinement in a gilded cage, and Escobar got a tip that the Colombian justice system was planning to transfer him by force. Did the tip-off come from one of his associates? From a guard he bribed? No one knows, but what is known is that while the army surrounded the prison to take him into custody, he found an exit and disappeared into the night with his associates. The government responded quickly, assembling a massive manhunt with the help of United States authorities, but no traces of the drug kingpin could be found. The private army he had quietly assembled had struck again. But that army was about to become much more literal. The government made Escobar public enemy #1 again, and he laid low for about a year. In 1993, he sent a letter to the country’s Attorney General - declaring war. He stated that he wouldn’t surrender peacefully and would instead form his paramilitary group - the Antioquia Rebel Movement, named after Medellin’s home province.

Combining the ruthless tactics of the cartel and M-19 with a more traditional military style, the group vowed to resume the kidnappings and bombings that defined his rule until now. The government would escalate, and the bloody war was reaching the end of the road. Now that the agreement had fallen apart, the Colombian government enlisted the help of the United States - who still wanted to get their hands on Escobar ever since the Avianca attack. Not only were Seal Team Six and Delta Force now looking for him, but they also trained a new branch of the Colombian police. A group of civilians who had suffered due to Escobar formed their vigilante group, targeting Escobar’s associates and his property.

The enemies were closing in, and Escobar’s time was running out. Even the most heavily armed man in Colombia could only run so long. Colombian surveillance teams had tracked Escobar using his cell phone transmissions and found him living anonymously in a lower-income area of Medellin - a far cry from his mansions. A team of eight government agents stormed the house, engaging in a shootout with Escobar and his bodyguard. The famous drug kingpin was finally felled by a fatal shot through his ear. No one knows exactly who took out Escobar, but even the complex link of supporters that Escobar had built couldn’t protect him forever. This sent shockwaves through Colombia’s criminal sector. The rival Cali cartel was able to take over much of the market - and more significantly, they now had access to the complex network of soldiers and informants Escobar worked with. No one knows exactly how big his private army was, but it’s believed that it not only involved heavily armed bodyguards who could defend him in a firefight and civilian informants who tipped him off to government actions, but agents within the government who may have protected him from reprisals and helped him stay out of prison. Of course, if you ask most of them, they’ll tell you they never had anything to do with Escobar - and you probably shouldn’t ask twice.

Pablo Escobar might be gone, but the model he built in Colombia has changed the world. Today in Colombia alone, the guerilla group FARC wages an ongoing battle against the government since the group’s founding in 1964. While they’re primarily a political group, they’re heavily involved in the production and distribution of drugs - meaning the government of Colombia is often battling against the private military of drug gangs once again. And closer to the United States, just over the border in Mexico, the cartels have their armies. But they’re not always waging war against the police or government. The Cartels in Mexico are in a high-stakes battle for territory, and each one is heavily armed. Based in major cities like Tijuana and Acapulco, they build up soldiers and weapons - and while they usually maintain enough peace during the day for their cities to remain safe for excited spring breakers, when the sun goes down all bets are off. Tourists know that to stay safe, it’s best to stay out of the sights of these warring armies. Around the world, other extra-governmental forces collect their militaries. And they often try to seize control of the government when they get strong enough. Pablo Escobar may have failed in his attempt to control Colombia’s government, but his tactics lived on to be used by illegal organizations around the world.

While some coups are funded by the military or established branches of the government, it’s as common for revolutionaries to be run by independent groups - who often hire members of the military away from the government. Even Colombia’s government is constantly working to keep FARC and the heirs to Escobar’s empire at bay. This means in some ways, the Kingpin of Medellin may have had the last laugh.

About the Creator

Jayveer Vala

I write.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.