Robinson Crusoe and the Colonial Legacy

By Doc Sherwood

Part One

The character Friday in Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) is of comparable significance to Shakespeare’s Othello. Between them, they are probably the two most important nonwhite figures in all English literature.

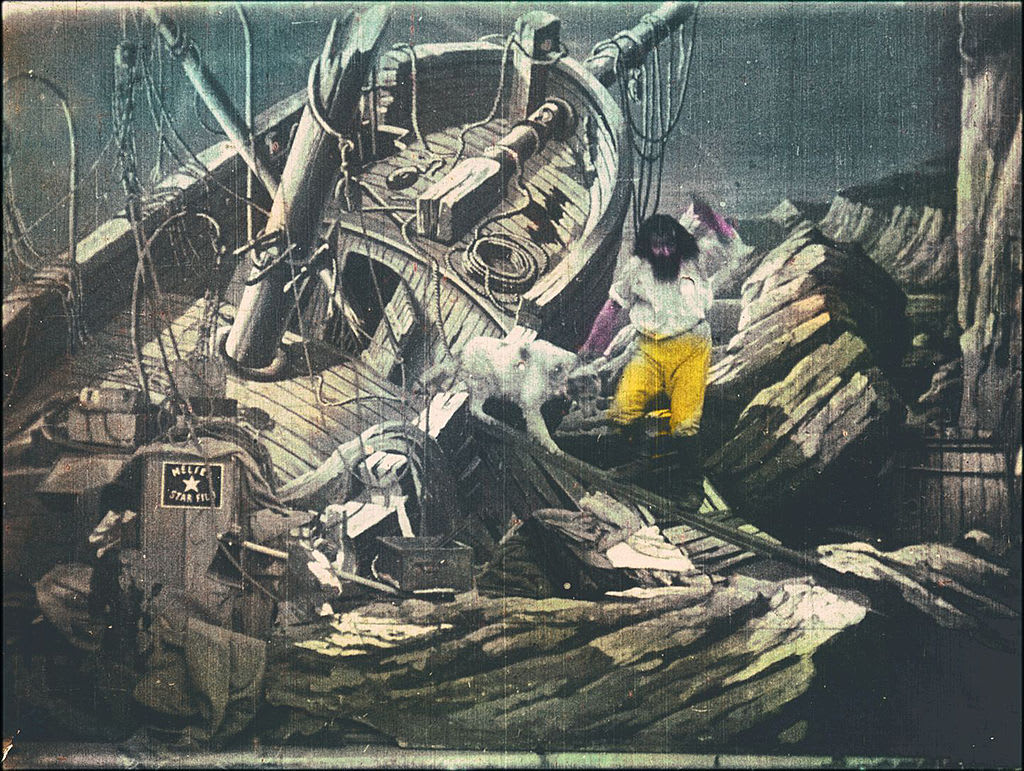

Friday is introduced soon after Robinson’s solitary castaway life on his island changes forever, the day he finds a footprint which is not his own. Robinson soon learns that his adopted island is in fact in constant use by local warring tribes of cannibalistic savages. These man-eaters use the beach as a site for their gruesome rituals, in which captured enemies are roasted alive and eaten. It’s at this point in the narrative we meet Friday, a native prisoner Robinson rescues from the enemy tribe and names after the day of the week on which the incident occurs.

Although Friday is often depicted as Afro-Carribean, the novel’s physical description of him makes it clear he is in fact a native South American, not a West Indian of African descent. However, a far more difficult question to answer is what Friday is, as regards his relationship with Robinson. Before they meet, Robinson contemplates making some of the savages into his slaves, principally to teach them obedience and thereby keep himself safe from their violence. Later, when he is saving Friday’s life, Robinson ponders the sentiment “that now was my time to get me a servant, and perhaps a companion, or assistant.”

“Slave,” then, has by now been upgraded to “servant,” which is at least a slightly preferable position. Nevertheless, we cannot forget that Robinson kept slaves on his plantation in Brazil, and was indeed bound for Africa to obtain more when he was shipwrecked on the island in the first place. The English slave trade was at its height in the early Eighteenth Century when Daniel Defoe was writing Robinson Crusoe, and it’s certainly a valid criticism of the novel that the evil of slavery in and of itself goes unchallenged throughout. Robinson on a few occasions mentions the slave trade, and it’s clear he sees it as no more or less than a legitimate business. Indeed, he even regrets becoming an adventurer himself, reasoning he’d have spared himself all the trouble of the shipwreck if he’d only put his faith in legitimate slavers instead.

Since Robinson does not mean to kill Friday, and the enemy tribesmen do, Friday in one sense benefits from being rescued. Nevertheless, it can also be argued he merely exchanges one form of captivity for another. Robinson teaches Friday to call him “Master,” sets him to work, and converts him to Christianity. None of this suggests a friendship on equal terms.

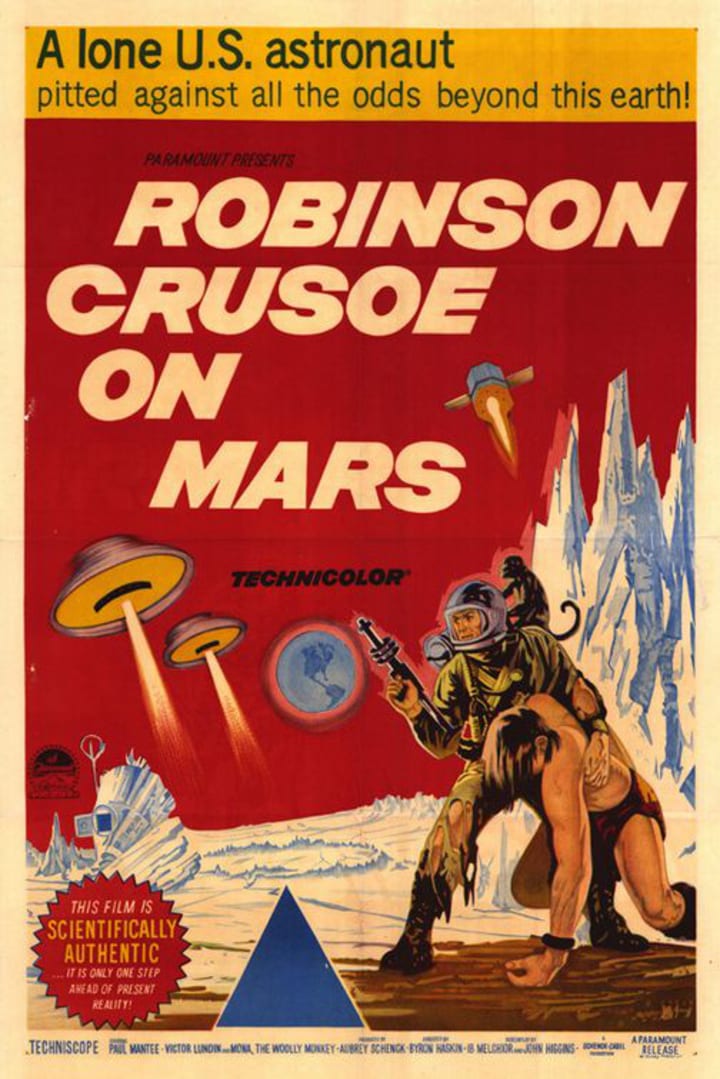

Director Jack Gold in his 1975 film Man Friday explored these troubling elements of Defoe’s novel, by portraying Robinson as a cruel slavemaster and Friday as the hero. In this reworked version of the story Friday fights to escape Robinson and finally wins back his freedom. At the other end of this pole is surely Byron Haskin’s 1964 science-fiction treatment Robinson Crusoe on Mars, which interprets Friday as an alien enslaved by another extraterrestrial race, and it’s Robinson who sets him free. The duo then go on to help and learn from each other, turning the film into an archetypal buddy-movie – even to the extent of Robinson teaching Friday what the word “buddy” means! Both these film texts, however, can be understood as gestures towards addressing or redressing the question of slavery in Robinson Crusoe, which Defoe’s original book leaves an ambiguous and disturbing undercurrent.

Part Two

If Robinson Crusoe is about a series of incidents that happen to one man, then the novel is a story about survival and the strength of the individual human spirit. If however Robinson can be seen as symbolic of something larger than himself, then he becomes a source of interest for postcolonial theorists.

Robinson does not come to the island by choice, and nor does he profit financially from exploiting its resources. In these respects, he is not like a colonizer. However, certain other aspects of his conduct while he is on the island do suggest that Robinson represents a particular set of values related to English colonialism of the Eighteenth Century.

Unto a land that was wholly wild and untamed, Robinson introduces agriculture, basic architectural techniques, and technology including guns. He frequently refers to himself as the “king” or “governor” of the island, and calls his two dwellings his “manor” and his “country house.” On most of these occasions he is, of course, being deliberately ironic. However, this transplanting of familiar English phraseology to a foreign setting was another key trait of colonial discourse.

Moreover, he takes Friday as a servant, even though this part of the world is Friday’s land and Robinson is an outsider. In this, above all, Robinson can come to resemble a colonialist.

In converting Friday to Christianity Robinson is not enacting a process that belongs exclusively to colonialism – such missionary work is in fact still conducted today. Religious conversion was however widely practiced on native peoples in the colonies, usually as part of colonialism’s myth of a “civilizing mission.” Much abuse and hypocrisy was committed under this pretence, yet it’s obvious Robinson considers it part of his duty to civilize Friday. Indeed, since one of the most significant components of this is that Robinson must teach Friday to stop eating other human beings, it can be argued that Daniel Defoe, by portraying native peoples as murderers and cannibals, uses his novel to validate colonial notions.

Other dimensions of this demand scrutiny, however. When Robinson first learns of the cannibals he is so shocked and disgusted by their ways that he contemplates killing them, but ultimately decides against it. His reasoning is that he has no right to take the lives of fellow men who have done him no harm, and who in addition have never been taught it is wrong to eat each other. Robinson resolves instead to leave their final judgment to God alone.

It’s crucial to note here that no matter how different the savages are to Robinson in their behaviour and appearance, he does not hesitate to perceive them as human beings. One of the foremost arguments of British anti-slavery campaign was predicated on the truth that black Africans were just as human as white people, and likewise had souls. That being so, slavery was forbidden by the basic dictates of Christianity. It’s also true that much colonial discourse regarding the “civilizing mission” was designed to inscribe the colonial subject’s status as somehow less than human, in order to legitimate such practices as slavery and exploitation. All this should be borne in mind when we read of Robinson, considering Friday’s people, and reflecting that God:

“...has bestowed upon them the same powers, the same reason, the same affections […] and all the capacities of doing good and receiving good that He has given to us.”

In the climate of the Eighteenth Century, this will have made for a powerful assertion of a point of view we now know was far ahead of its time. Hannah More in 1788 wrote one of the most famous attacks against the slave trade in her great poem ‘On Slavery’, which displays considerable overlap with the passage from Robinson Crusoe quoted above. More will have read Defoe’s novel, as it was one of the most popular texts of her time. It’s even possible she drew direct inspiration from Robinson Crusoe when writing ‘On Slavery’, but at any rate, she will certainly have found a strong and reassuring resonance between her convictions and those expressed in the earlier book. Robinson Crusoe then, for all its troubling nebulosity on the issue of the slave trade, may also have contributed to a much-celebrated denouncement of that entire institution.

Conclusion

As we’ve seen, the question of whether Friday starts out Robinson’s slave or servant is difficult to determine. The difference is usually that a servant is paid for their work and is free to leave, whilst a slave is not. Obviously it’s impossible for Robinson to pay Friday, as money has no meaning on their island (although the film Man Friday adopted an intriguing perspective on this). Whatever Friday might have been to Robinson in the early days, however, there’s no doubt that as time goes by they become firm friends. The idea of slavery or servitude is soon forgotten, and ultimately the two men leave the island together to seek adventures new.

It’s a commonplace of literary studies that the interpretation of texts changes greatly over time. Some books become more relevant to later generations than they were in their own era, and likewise others fall from favour as attitudes change and develop. Much postcolonial theory is concerned with the latter group, where beliefs and practices of colonialism that are now known to be wrong are endorsed. In a text such as Robinson Crusoe, however, we see much complexity and ambivalence regarding questions of race, imperialism and the so-called “other.” Defoe’s novel reminds us that close study and a questing mind are the tools with which to discover the truths behind any literary masterpiece.

Comments (2)

Dear BookDocBro; formerly known as DocKnickerLess. This comfortable niche within this newly established category was implemented certainly with U'z in mind. Yes, as generations hand down versions of tales - Who but you would pick out the 'Mars' Theme. As I climb out of the 'Dunce Department' with your learnin' I hope you'll grade me on a curve? J-Bro

Enjoyed this. Some very good points