Stanley Gray

Bio

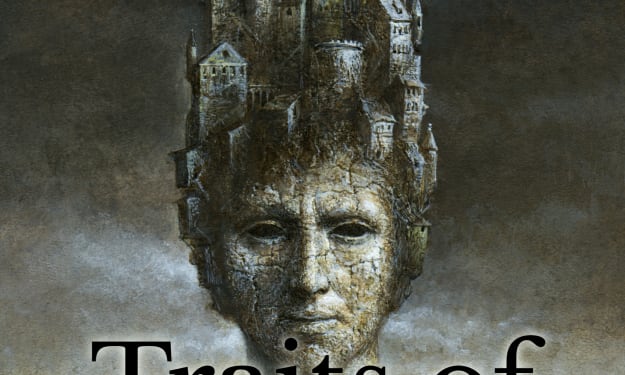

Stanley Gray is an award-winning writer who creates exciting stories with flawed characters. Traits of Darkness, the first in its series, is available on Amazon. He lives in beautiful Oregon, and loves spending time with his cat, Calypso.

Stories (6/0)

Bonus Content: 4 Reasons to Be Afraid of New Amazon Rules for Authors

Do you hate cheaters? Most of us do. And rightly so. When there are fair, transparent rules meant to level the playing field, it is precisely those rules that can create a framework for people to flourish under. Yet, just like in the popular board game Monopoly, many of us have encountered people who might try to bend the rules in an attempt to gain some perceived advantage. Friendships can be ruined, trust can be broken in those moments. It is easy to feel as if something tangible has been taken from you, when someone uses unfair advantages to acquire a temporary advantage. Even if you beat the cheater, the damage has already been done: you know they don’t always abide by the rules.

By Stanley Gray6 years ago in Journal

Three Reasons Donald Trump is Wrong About LeBron James

Allow me to begin by being up-front about something: I am not a LeBron James fan. Born and raised in the Indianapolis area, I grew up idolizing Reggie Miller, Rik Smits, Dale Davis, Jermaine O’Neal, et cetera. As the game of basketball evolved, the names and people I rooted for changed, but the team did not. There were many years when LeBron James almost single-handedly delivered the fatal blows to my Indiana Pacers’ championship ambitions. His years of dominance in the Eastern Conference are thankfully over, and I confess I did not feel a single moment of sadness at watching him depart for Los Angeles.

By Stanley Gray6 years ago in Unbalanced

Need a Great Summer Read? This Epic Fantasy Novel Is It

Chaos reigns. In a remote island kingdom, a tyrannical king indulges his basest desires. He murders for pleasure and terrorizes the peasants who have built his empire with their backs. Yet, the king’s madness may be preferred to the horrible cruelty of his son and heir to the throne. As the callow prince and his mother the queen conspire to commit the ultimate form of treason, the people of Norteras clamor for justice and talk openly in the cobbled streets on a revolution. A dragon has been prophesied to come to the land to save the oppressed and vanquish the nefarious overlords.

By Stanley Gray6 years ago in Futurism

Barb's Barbs

We knew when she stumbled in at 5 AM that she would be trouble. With an unruly mop of curly brown hair that declared open war on conventional notions of hygiene, a sallow face, and the attire of someone more likely to be a guest of a nearby condemned house, she did not possess the appearance of a normal guest. She, however, had a reservation, and that was the most relevant factor. While the normal guest at the Hilton-branded hotel would be in a dress shirt or a chic dress, money, not fashion reigned supreme. Front desk agents aren’t judges of character or arbiters of sartorial splendor. And Eugene is an odd enclave of artistic self-reproach. Barb was one of the reasons we played a game behind the desk, where we guessed whether someone was a business owner or a homeless person. You just never knew.

By Stanley Gray6 years ago in Journal

Freedom on Alcatraz Island. Top Story - July 2018.

The once-familiar sounds of doors clanging shut did not make me cringe or dredge up suppressed memories. Instead, they had the curious effect of bringing me a sense of peace. Integrating a difficult past into a present inextricably intertwined with a single impulsive action committed long ago can be hard. Many people that have been to prison allow their imprisonment to become their identity; you become known as a felon when convicted. Yet the process of reintegration after a long stretch of incarceration often means reconciling the two. And it was this reconciliation that took place during my recent trip to Alcatraz.

By Stanley Gray6 years ago in Criminal