Kayaking Is Not Cancelled

Seeking the sea for self-care during this pandemic... come float with us on Canada's west coast.

I am floating.

Feather-like, suspended on the surface, I am still. Observing. Looking down, around, up, I am wrapped in nature. I am free. It can’t get me here is the way I see it, and I hear that echoed around me.

We’re safe out here!

Couples clinking wine glasses call out from sailboats. Families building driftwood forts nod from the shore. A guy in a homemade plywood rowboat raises a red oar. Fellow kayakers glide by and tip a paddle as they dip, purposefully, peacefully. Kiteboarders haul in their sails and enjoy a brew on shore, evenly spaced, visible at a distance by their sails, bright blue and neon green and outrageous orange in the slanting afternoon sun. A paddleboarder passes at a distance, head held high, scanning the inky swells, not lost at sea, but found here. We all are. We seek the sea for solace, for calm, for protection, for distraction, for rejuvenation, but mostly, for escape.

COVID-19 can’t get us out here. I hear it again and again. In this, we are one.

As I float and bob and drift, my mind does likewise, drifting, floating, and at times bobbing, bouncing up and down, back and forth, reconciling how at a distance the world has changed, flipped, become unrecognizable.

And yet here, up close, hovering on the surface, nothing changes: blue herons continue to strike poses, steadfast stalkers poised to poke and pierce; eagles soar, elegant and fierce, eyes on the water, yellow talons extended like gnarly landing gear; seals pop up around us, curious, earnest, playful, hungry and big-eyed; sea lions bellow farther out, tracking herring, hungry hunters; farther still, plumes of vapour bisect the shoreline and we spy them, blasting, surfacing, shiny and black, the final link in the Pacific food chain: orcas.

It happens every spring, this chain, this chase—pandemic or not. The herring, the seals, the sea lions, the eagles, and the orcas are not aware of the drama unfolding on shore. They do their thing, oblivious, continuous. Life goes on out at sea.

And that’s why we seek it, this nature-nurture: in nature, we trust. We seek its rhythm. Life as usual. Normalcy. Calm amid chaos. We seek to escape, to float, to observe, to be wrapped up, to be delighted, to savour, and to be safe. Here on the west coast, we seek the sea in droves, each of us in our craft of choice. Ours is the kayak.

Kayaking is not cancelled. Out we go.

Although we often paddle a predictable path, no two outings are alike. With the tide and in time, the ocean leaves us gifts. It tells us stories. We need to be vigilant observers, open to noticing. And we are. We do.

But first, the path and the process.

We live on a bluff over the ocean, two roads up, so we carry our kayaks downhill to the shore. That’s step one. In front of us is an intriguing landform, perfect for exploration: a spit of land extending out into the harbour, a bit like a dogleg with canine toes splayed at the end.

But the way I usually describe it is more like an anatomical command: extend your left arm out in front of you, bend thirty degrees, and your arm becomes this spit of land. On your shoulder sits our house.

Your upper arm is the causeway, with beaches on either side. The outside is rougher open ocean. That shore is dotted with fire rings and strewn with driftwood and logs, perfect for fort-building. The inside is sandy, protected, good for kayakers, and in stormy weather, for kiteboarding enthusiasts.

Now, travel down to your forearm, beyond where the bend is. This portion is a military cadet camp, home to an international crew of eager cadets each summer.

At the very tip of your arm and this spit of land are your fingers and three bays: the gaps between your fingers. We call these quiet coves—from index finger to pinky—Heron Bay, Marina Bay, and Totem Bay. Each is home to its namesake.

Bigger picture, over your shoulder to the left rest the mainland mountains, distant and craggy, like the snaggle-toothed peaks beyond Seuss’s Whoville, whimsically pointy and suggestively sinister, snow-capped, menacing. To the right and in front lies the island mountain range, closer and pleasingly smooth, Sound of Music-like, familiar and accessible. The jewel is the glacier, sleek and white, like a mammoth mother Persian curled up amid her litter.

That’s the backdrop, your arm and hand, submerged in the sea, framed by mountains far and near. On we go.

We ease our kayaks into the edge of the bay, across from your hand. And then we do what we always do: we paddle across the stretch of water, heading for your forearm and a collection of shipwrecks. That’s what I call them, but in fact, they are two rotting and abandoned homemade boats, washed up on shore. I prefer to think of them as heroic, so I call them shipwrecks.

“Meet you at the shipwrecks!” I call out to my son and husband, and off I go.

And this is where the story takes a turn and becomes a choose your own adventure odyssey (in my mind). I have choices, and although they have been curtailed and clipped on land, out on the ocean I am in control. Here in my kayak, I am free to choose. I slow my strokes and I hover. I bob. I imitate.

For what has happened is this: I’ve entered a jelly cloud, a patch of water filled with pulsing, translucent jellyfish, floating, pumping, rhythmic and beckoning. I slow down and then stop, still, watching, floating as they do.

Soon there are dozens. Hundreds? I stare down at them, an admirer of their delicate perfection: discs, feathery yet resilient, worker bees pumping, filtering and yet synchronized and sophisticated, simple and systematic. They become a ballet, and from my boat, I their admirer. The pulsing is calming, eloquent. Eventually I paddle on. This journey unfolds.

I reach the shipwrecks. The larger of the two is my favourite because it’s a classic homemade, tubby-looking boat, a chipped and worn bath toy, resting on the shore at a three-quarter angle, resigned, recently pepped up with graffiti art. It looks like a rainbow Bob Marley from where I sit. Isn’t retirement grand? That’s what this boat says to me. I smile up at it, bleached and beached there, warm and tattooed in the gold late-day sun.

My son Erik catches up. We hover close to shore and wait for hubby and dad, Frank, to catch up, too. Neither of us speaks; we are both locked on to the ocean floor below us, magnified, like peering into an aquarium touch pool: broken bits of algae-covered oyster and clam shell; barnacles, grey and persistent, adhere to everything that does not move; and sea grass, moss green and mauve, sways gently to the rhythm of our crafts. Over there . . . a shard of glass, bottle-brown. Beer? A beach party?

“I love this, floating here . . .” I say to Erik. “It’s like a Disney water ride where you don’t have to do anything but sit and look.”

He nods at me, unspeaking. In leaving the land behind, we put that life on hold: the headlines, the hand sanitizer, the alarming numbers, the predictions, the tragedy. Here we can float, detox, reset, rejoice.

Hovering on two feet of clear Pacific water, we have morphed into ride-goers, something between Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean and It’s a Small World. We become observers in blue-and-white boats, mechanized by the current as it sweeps us parallel to the shore. We are drifting toward your thumb. Goodbye shipwrecks and touch pool. Goodbye wrist. On we go.

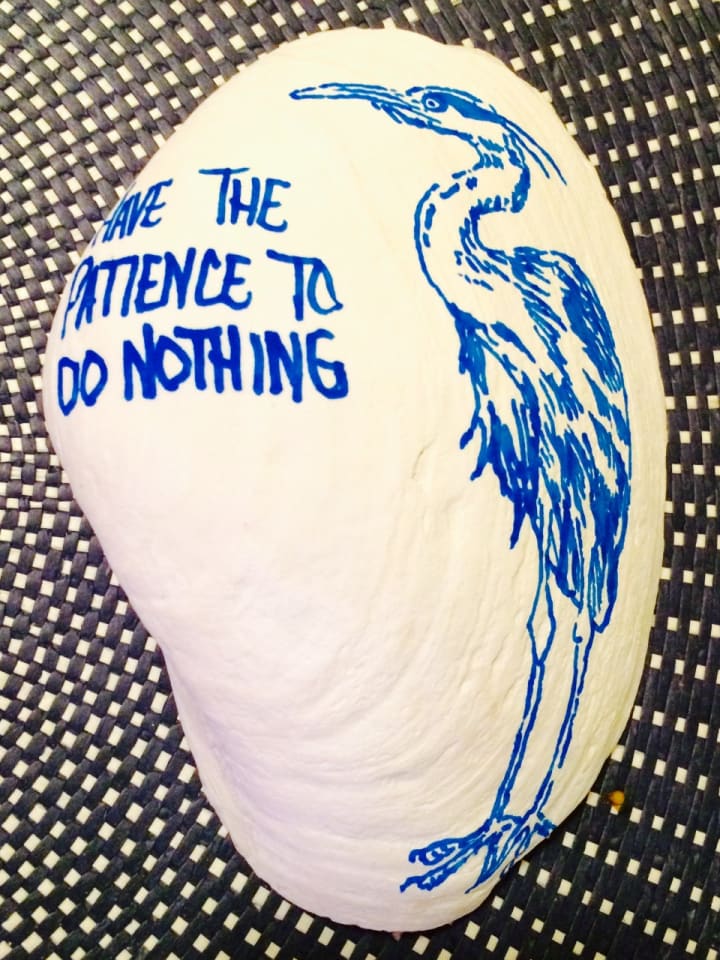

Heron Bay. This indent is the smallest and most unremarkable of the three bays, and yet it is here I notice most. Flanked by straw-like shore grass, Heron Bay is shallow and deserted, except for the pair of herons we once observed here, stoic, statue-like hunters. Have the patience to do nothing came to mind that day, and here, I do exactly that. Closing my eyes and lifting my face to the sun, I pause and listen. Eyesight eliminated, my hearing becomes masterful. There is much to take in.

What I notice most is the sound of water: the swells as they stroke the shore; the pleasing swish and slosh of Erik’s and Frank’s paddles exploring the bay; a sudden gush of rhythmic waves as they round the bend and smack sand. I do not see them, but I imagine them evenly spaced, like musical staff lines, bending and breaking as they collide with the shore. I hear the occasional gull, the rusty-clothesline screech of a distant eagle, the purr of a small plane. A Cessna?

Marina Bay is next. It’s the largest and is home to a collection of boats belonging to the cadet camp. Over here, a line of faded sailboats, dressed down, resting and awaiting a new rotation of cadets. Over there, larger boats, pleasure craft. I discover, with a smile, song boats, love boats, and kid boats.

Among the sonorous is one called Against the Wind. Bob Seger, soulful, reflective, downloads within: “I’m older now but still runnin’ against the wind . . .” Another is Summer Breeze. The wind abates; the soundtrack shifts. “Summer breeze . . . makes me feel fine. . . . blowing through the jasmine in my mind . . .” Ah, yes. Seals and Crofts.

The love boats are next. Three: Magnetic Attraction, Goodnight Irene, and G. Louise! And over there, the playful kids’ boats, whimsical and light: Oz and Peter Duck. I need to see these names, all of them, a reminder that lightness and love are alive and well.

Totem Bay. We’re almost there, to the tip of the spit, to your baby finger. But first, a wide but shallow bay where a single, stout, freshly painted totem pole resides and presides. The effect is spiritual. Maybe for this reason, I find myself reflecting. It is here I paddle and make sense of uncertainty. It is here I float and squint at the surface of the ocean, sparkly, dazzling in the afternoon light. It is here I process change. Erik paddles up beside me.

“This is my skating in circles,” he says quietly, and I know exactly what he means. He is referring to our backyard skating rink in Ottawa, and how we used to skate in loops. Loops helped us to think, to understand, to process.

The three of us paddle together now, and exiting Totem Bay, we reach the sandy tip of the spit, deserted and exotic, for here stand two quirky driftwood shelters, makeshift and yet permanent. They have been here for as long as I can remember. What are they? Cadet projects? Survival huts? Equal parts creativity and random piecemeal construction, these unusual shelters offer a break from the summer sun. There are also two small driftwood totems jutting from the sand not far from the larger hut. Carved, grimacing faces give the beach a Polynesian feel. Exotic. Tropical.

But it is not to shore I paddle on this day. I head out toward the sailboats anchored in front, and as I glide by, I hear them, voices tucked inside or cast on deck, sound bites as I pass: “COVID-19” and “pandemic” and “death toll” and “Italy.” The conversations merge, converge. Processing, endless processing.

And then something unexpected happens. I call out to the fellow on the white sailboat. He is sipping beer from a mason jar.

“Did you see that, just now, the blowholes out there? Orcas!”

I am bursting to speak, to mix and mingle . . . to make random connections with perfect strangers. To make up for lost time. To fill my chit-chat quota. I can out here; it’s safe. And to my surprise, I find myself paddling from boat to boat, calling out, feeling talkative and a lot like my grandfather, Jack, rejoicing in what is hard to do on shore: connect.

A fishing boat passes, and we wait for it, the cascade of waves that will surely come our way. They do, soft, even swells that lift and buoy us. It feels like a haiku out here.

And that COVID-19 can’t touch us.

Leaving your hand for open water, we head back toward your shoulder, for home. Reality.

I never knew what I liked so much about kayaking until now. Strangely, it took a pandemic to offer clarity. I return refreshed and reset. Ready.

The float has been heavenly.

____________________________________________________

"Kayaking is Not Cancelled" is part of a new publication Not Cancelled: Canadian Caremongering in the Face of COVID-19.

Authors Heather Down and Catherine Kenwell gathered stories from every province to illustrate the effects of COVID-19 and the ways in which ordinary Canadians are performing extraordinary acts of kindness and self-care during this pandemic.

"It became clear that there would be limits on social gatherings, routines, and regular day-to-day situations," Down explains. "But there was so much that couldn't be cancelled—our Canadian spirit, our humour, our love for one another. So we created a project to shine light on the positive stories of ordinary heroes."

The e-format edition is available on Chapters Indigo with the softcover to follow on June 5, 2020.

___________________________________________________

About the Author: Teresa Hedley is the parent of three young adults, one of whom, Erik, has autism. She is also an educator, an author and a curriculum designer. As a teacher-trainer, Teresa taught English in Canada, Japan, Greece, Spain and Germany. Teresa's memoir, What's Not Allowed? A Family Journey With Autism is available on Chapters Indigo and will be released in October, 2020. She and her family live and play on Vancouver Island.

About the Creator

Teresa Hedley

Greetings from the beach... where you'll find me exploring, reading, writing, hiking and kayaking with our local seals. I'm excited to share my stories with you via What's Not Allowed? A Family Journey With Autism. Now on Amazon + Chapters

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.