Diddling with Datums

The challenges of sailing with old nautical charts in the modern world and why GPS isn't always the right answer

People wonder what it’s like living on a boat. There are many daily problems and challenges — and just trying to find any wine in Indonesia is a big one for me right now.

And knowing where you are on the earth’s surface is one of them, the biggest.

And it’s not always straightforward.

Old techniques

Just a few weeks ago I had cause to use an old technique for position fixing at sea, but this time it was in reverse.

We were approaching the coast of New Guinea from Tual in the Kei Islands.

Sailing at night is not recommended here as there are many unlit fishing boats and also unlit Fish Aggregation Devices (FADs).

And to top that the navigational charts warn that navigational marks (e.g. buoys) are unreliable (missing or lights not working). So to be safe we wanted to anchor off Adi Island for the night given that the approach to Adi is simple and free of dangers. Then we would make our mainland New Guinea landfall at Triton Bay in daylight — an easy forty mile daylight leg.

Problem

Sailing in Indonesian waters, the electronic and paper charts are way off the mark, with differences between the charted position of say, a rock, out by as much as a mile as against its ‘true’ position. That happens because the modern electronic and paper charts are all based on what’s called the WGS84 datum which refers to the World Geodetic System of 1984 (prior to that there were hundreds of different datums worldwide, as well as earlier WGS models). GPS positions are referenced to WGS84, a worldwide model (geoid) of the Earth.

By now, most nautical charts have been digitized and positions corrected to agree with that WGS84 datum; paper charts have been re-aligned (although paper charts disappearing into history). These corrections — offsets — have been applied, but many charts are still out of sync.

The Indonesian charts (paper and their digitized versions) are largely based on relatively poor Dutch surveys of 1904. The datum point and other key features were established using a sextant and timepiece and if that was not accurate then errors multiplied. The paper charts are generally OK to use with traditional navigation methods, but problems occur when using GPS (‘satnav’) to fix positions on them — or on their digitized version.

So, in summary, the ‘layout of the land’ is not necessarily accurate, it doesn’t sync with the GPS geoid and the digitization process just replicates the problem. And apart from the positional and landmass shape mismatch, the sea bottom is poorly surveyed in many areas — but that’s another story entirely.

Important shipping areas around Jakarta, other major ports and towards Singapore have been re-surveyed. But not all areas — for example the areas I have been sailing in and around the Spice Islands and New Guinea.

I have two versions of the CMap e-charts — one dating from 2007 and one more recent version which I bought in 2018 has been corrected — at least to align positions with WGS84.

‘Aligned’ they say — but can the latest charts be trusted? I had two versions to compare.

Solution

The errors vary, even between the different brands of e-chart (CMap, Navionics and Garmin are among the most commonly used brands in small boats). When ‘a prudent sailor’ is approaching land he or she will want to check the chart error.

That’s something that we never had to do in the old days — we referenced our estimated position by taking compass fixes of land objects and plotted them on the chart and then shaped our course accordingly. There were a few other techniques too, such as horizontal and vertical sextant angles (surveyor-type stuff). We also took astronomical sights, but these have their limits too, especially on a small boat pitching, rolling and yawing.

And then there was dead reckoning, which can be more of an art than a science: Where was I — and when — and how fast have I moved in what direction since then? Oh, and don’t forget to allow for tides and other subtle effects such as leeway.

Depth sounding was and still is very important, but I’ll get to that later.

So, these days we know exactly where we are relative to the geoid — the GPS model of the Earth’s surface. But as we just saw, the old charts do not always align with the geoid.

Right, so we don’t always know exactly where we are when we look at a chart — electronic or paper.

But we can fix our position on the chart relative to visible objects.

There is still no substitute for the Mark 1 eyeball!

The compass fix

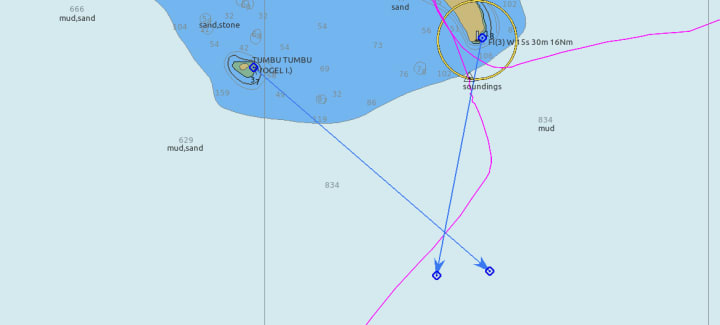

So, as we approached Adi, the small lighthouse on the southern tip of Adi was easy to identify by eye, as was Tumbu Tumbu (Vogel Island). I used a hand held bearing compass to take bearings of the two distinct objects and then plotted them on the e-chart.

The bearing lines crossed nicely at the place I thought I was at, but I was still suspicious.

So I watched the echo sounder.

The echo sounder

The echo sounder (which the old sailors had in the form of a leadline, ‘armed’ with tallow to take samples of the seabed) is an invaluable aid — it works in all weathers from fog to storms. My unit reads to depths of about 187 metres, which is more than adequate for most needs. But I don’t have the new fangled forward looking sonar so I cannot detect an uncharted rock or reef which may be lurking ahead.

However the sounder can be used to detect a known, charted seabed feature, such as the edge of the island shelf or shoaling water, even a reef that is safe to pass over. As long as they are charted. That can provide an element of positional cross-checking.

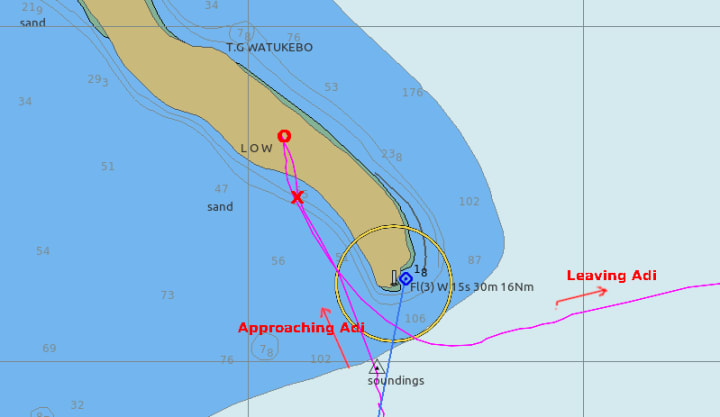

So, as I approached the island of Adi in New Guinea, I watched the echo sounder and put a mark on the e-chart when soundings were detected (i.e. I was seeing a depth of 187 metres or less). The only problem was that the charted soundings were sparse and I had nothing to compare with. The 100 metre depth contour (edge of blue area) is approximate only. But I knew the water depth would be decreasing.

As an aside, in these waters the islands stick up out of very deep water with nothing in the way of a ‘continental shelf’ such as you see off Europe or the eastern USA. Indonesia is tectonically very active — think Krakatoa, earthquakes and tsunamis; the Java Trench at over 7,000 metres is one of the deepest parts of the world oceans.

You can see on the chart excerpt above that as I approached Adi the depths changed rapidly from over 800 metres to less than a hundred in just a few cables (1 cable = 1/10 nautical mile = 200 yards). In comparison, most of the English Channel is less than 60 metres deep and carries a huge volume of shipping traffic. But it is very well surveyed!

And, as I recently wrote, the Prince of Wales Channel through the reef-strewn Torres Strait, just a few hundred miles from where I am in Indonesia, takes large ships with little more than one metre of clearance under their keels. Accurate surveys and very accurate positioning are a must if disaster is to be avoided. And ships pilots are mandatory.

Other modern aids to navigation

Radar gave me the range and direction of a feature, so I could check the position of Vogel Island. That agreed with the crossed bearings, within the error limits — a low tree studded island is not a good radar target and the echo is not sharp; additionally the bearing is relative to my boat’s heading, which is not completely steady. The echo from the tip of Adi where the lighthouse is also supported the fix.

Feeling our way in

I’d selected a point on the chart which looked suitable for anchorage and we felt our way in slowly, watching the echo sounder and watching the colour of the sea — the water is clear here and reefs are visible by discolouration. When I thought we were in the right bay and depth, we dropped anchor.

The chart excerpt below shows our final position, in a safe depth of water, ‘O’, and where we intended to anchor (per e-chart — 2007 version) ‘X’. Ha! The difference in position is 0.94 nm, 344⁰ True.

The 2018 chart version was better. At least we were not on the land. However, since then we have discovered that even that 2018 version lacks accuracy in some places here in New Guinea. It cannot be relied on entirely and the errors vary from place to place. That is of course due to the (in)accuracy of the original surveys.

It’s not quite a case of ‘garbage in, garbage out’, but you get the idea?

So, wherever we go in Indonesia, we have to check two e-charts, and proceed with caution…

Back up

Before we crossed from Australia to Indonesia, I re-tested my back-up echo sounder which I hadn’t used for years. No, it was not working and I was not surprised. That made me very nervous given the dubious charts and our reliance on accurate depth finding, the oldest and most important seaman’s ‘instrument’.

So, I headed off to the chandlers and bought a cheap fish finder (~$150). That is much more modern than my existing instruments and can act as a sonar — i.e. look ahead. It’s still in it’s box, but I look forward to trying it out — hopefully at leisure and not under duress. I just have to figure out a way of fitting the transducer (sender/receiver). We cannot haul out of the water for many months yet, so a temporary arrangement on a pole will have to do — just in case the main unit fails.

Not that we need fish anyway — our freezer is brimming with bluefin tuna and Spanish mackerel that the first mate landed in the last week.

Such is life on a boat.

There are easier ways to enjoy sailing and cruising, but right now I’m going to try and learn a few more words of Indonesian — and read up on the latest volcanic eruption on Java.

And the other news today is:

It’s all happening here…

***

Canonical link: This story was first published in Medium on 6 December 2022

About the Creator

James Marinero

I live on a boat and write as I sail slowly around the world. Follow me for a varied story diet: true stories, humor, tech, AI, travel, geopolitics and more. I also write techno thrillers, with six to my name. More of my stories on Medium

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.