"You're not like other girls."

This is a line many of us have heard in a film or TV show, usually said by the love interest to the heroine to praise her for her uniqueness. However, this is a bit of a backhanded compliment, especially when the praise is acknowledging traits many women have or insinuating its better not to demonstrate typically feminine character traits. That might be why this line is almost only found in young adult and teen media. Writers may not expect teenage audiences to analyse the subtext or larger social implications that dialogue can hold. By saying that your intelligence, sense of humour, chastity, lack of interest in makeup, independence, or whatever make you "different from other guys/girls," it's implied that anyone who identifies as other to those traits is somehow lesser than.

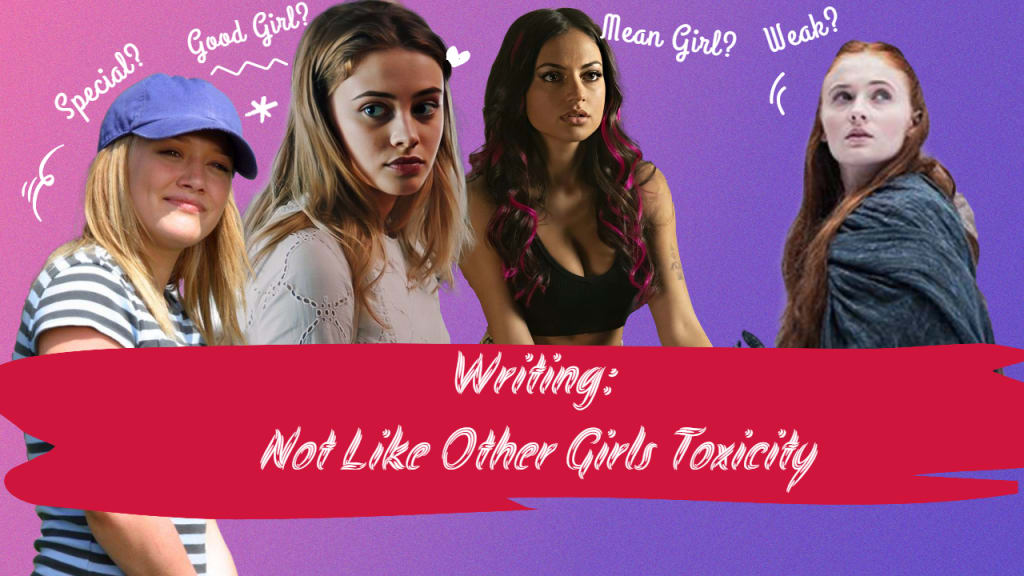

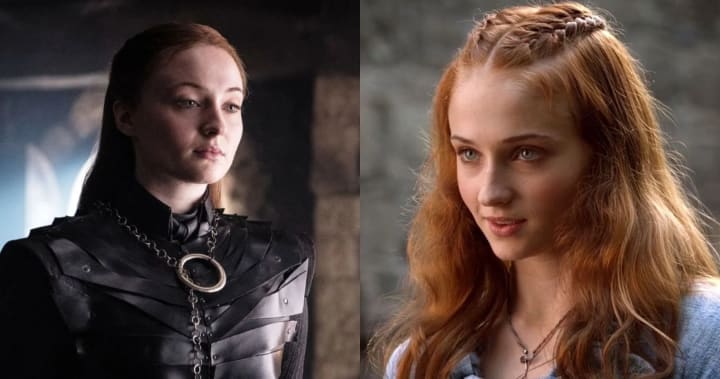

Take Game of Thrones for example, Sansa is a character who demonstrates more feminist traits in wanting to ultimately marry and be a mother that fans have criticised while at the same time praising her sister Arya for training as a warrior and identifying with stereotypical masculine traits. Yet Sansa has the characteristics of a strong leader, showing compassion and a steady conviction in later seasons.

Or in Buffy the Vampire Slayer how Buffy's sister Dawn is condemned for being a more "stereotypically girly girl" while her sister slays vampires and demons. Yet, both Sansa and Dawn show strength in other ways, whether its using their wits and compassion while their sisters rely on physical strength. Dawn and Sansa's traits are more identifiable as they portray the transition from adolescence to womanhood, but why is this frowned upon? Especially when these characters go through similar narratives of loss of innocence and becoming the better for it.

Where the toxicity comes into this is when writers prop their protagonist up for having a certain set of characteristics while simultaneously condemning characters who don't or won't have these characteristics - if the heroine is a virgin then any characters confident in their sexuality are "sluts", if the heroine is a tomboy then girly girls are annoying or if the heroine is smart then everyone else is dumb. Also these type of stories rarely portray healthy female friendships - it relies heavily on the Madonna/Whore Complex, as in one certain type of woman is good and the other is undesirable.

Look at A Cinderella Story for example. Hillary Duff's modern Cinderella is quite literally one of a kind in that world - she's a bookish tomboy with aspirations to go to university and aside from her godmotherly dynamic with Regina King, all the other female characters are cruel, dim-witted or superficially shallow. Sam has no female friendships nor do any of the characters have traits that many viewers identify with. It's hard to believe Sam is the only selfless sporty academic loving high schooler in that universe - but this forces the audience to identify with the protagonist, while also implying anyone who identifies with antagonist Shelby's femininity or stepsister Brianna's lack of academic skills is also identifying with undesirable traits.

There's even a scene in this film which uses the above statement - while Austin quizzes Sam on her true identity (despite seeing half of her face) he falls into the trope of comparing her to other women:

AUSTIN: Okay, I got it. Given the choice... would you rather have a rice cake or a Big Mac?

SAM: A Big Mac. But what does that matter?

AUSTIN: Well, I like a girl with a hearty appetite. And besides, you just eliminated about 50 percent of the girls in our class.

There is no way that 50% of a class of teenagers would prefer a rice cake over a Big Mac, but again this is another prime example of making Sam unique in her non-uniqueness. It contradicts itself - by saying Sam is not like other girls over something as trivial as that, it instead highlights how normal and unextraordinary she is.

Have we progressed since a nostalgic tween movie from 2004? Yes, in many ways - but productions such as Anna Todd's After franchise, Netflix's Tall Girl or Sierra Burgess Is a Loser drags the unhealthy "not like other girls" archetype back onto our screens with no new layers or complexity and instead falling on familiar tropes.

In the After series, Tessa - the generic nerdy good girl heroine - has her sexual awakening while away at university and cheats multiple times on her boyfriend, but she repeatedly slut-shames and openly calls minor antagonist Molly "a whore". Tessa's dislike of Molly is rooted in Molly's confidence in her sexuality and the fact she had a prior fling with Hardin. These attributes deem Molly as "lesser than" through the protagonist's eyes - even though Tessa's throughout the series is far more problematic. This internalised misogyny is projected onto Molly multiple times, but this contemptuous behaviour towards her is validated by the supporting cast.

In After We Collided, Tessa and Molly continue their antagonistic dynamic, coming to ahead during a New Years Eve party scene. During a drunken game of truth or dare in the book, Tessa openly calls Molly a "whore" in front of their peers, Molly is offended by the term and shuts it down despite Hardin and Tessa's insistence that she is. Molly then asks if it's true that Tessa is a dumbass for getting back together with Hardin after their relationship was nothing more than a bet. When Tessa declines this, Molly presses that it is true and begins to taunt Tessa with innuendos regarding her previous fling with Hardin. Overcome with rage, Tessa tackles Molly to the ground where they begin a fierce fight - which other characters proceed to praise Tessa for attacking Molly, no one calling Tessa out for starting the fight.

This is one of the many problematic elements, especially in its negative portrayal of female sexuality and slut-shamming. The sheer contradiction of Tessa being applauded on discovering her sexuality and a character like Molly being convicted for her own sexuality highlights the negative stereotypes of how women in this genre are written.

When writing female characters, you need to think of every character as the hero of their own story. Whether they're the hero, villain, love interest or supporting character - give them the complexity you would give to your heroine. The Not Like Other Girls trope is a weak substitute for trying to make your character special in very ordinary ways while leaving your other characters flat and underdeveloped.

Truth is, there's no such thing as not being like "other". Everyone is unique and people will identify more with well-written characters and not an idealised version of what some believe is the perfect woman.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.