In 2012, nearly two million people listened to this TEDx talk.

In 2013, another 2.3 million people bought Beyoncé's self-titled album whose radio single ***Flawless sampled part of it.

And in 2014, it was published as a book-essay, which was then distributed to every sixteen year-old girl in Sweden.

I refer, of course, to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's We Should All Be Feminists.

Now, I was not the intended audience for the talk when it came out. I was already a feminist in 2012, consuming feminist literature and theory voraciously.

But Adichie's charming talk stood out to me in this relatively saturated field, anyway.

Humour and tolerance: welcoming the reluctant aboard

Far be it from me to tone-police my fellow activists. You are furious at injustice, and rightly so. But what I like about this talk is the speaker's good-humour and understanding; she makes jokes and shares anecdotes and acknowledges the good intentions of the friends, family and strangers who have slighted her.

As a result, this is a wonderful piece for beginners. Accommodating for the defensiveness of those who don't like to realise how they have acted misogynistically, Adichie opens the door and gives a warm welcome.

Okoloma, the boy who first used feminist as an insult against her, she describes as one of her "greatest childhood friends".

The journalist who told her that feminists were just women made unhappy by their inability to find husbands, she describes as "nice" and "well-meaning".

The friend who couldn't understand how she was any worse done by than him, Louis, she calls a "brilliant, progressive man".

In essence, your ignorance does not make you evil; it just makes you ignorant. Feminism is an opportunity to overcome that ignorance: to rise above embarrassment and do something about it.

Fourth-wave feminism: looking deeper

Most of us struggle to identify sexism that isn't as concrete as the withholding of the right to vote.

Adichie peppers her rhetoric with real-life stories and unchallenged axioms we can all recognise. She exposes, in a matter-of-fact manner, the ways in which our normal day-to-day is underpinned by invisible power dynamics and gender assumptions.

She recounts the time when her male peer was given the role of class monitor when she had earned that role, because it wasn't a girl's role. It reminded me of how my secondary school, like most, had groundlessly gendered the sports of rugby and netball.

She recalls how a valet thanked her male companion when she had tipped him for his good service with her car. It reminded me of all the waiters who handed me the bill at the end of my dates with women.

She tells her close friend's story: being ignored by her male colleagues in a meeting and watching as they took credit for her ideas. It reminded me of all the times I'd watched my female colleagues' lips pursed in staff briefings, barely containing their indignation.

Misogyny is insidious, nowadays, not blatant.

For men, the first step is recognising our complicity in all this. I didn't fight for my girl friend's right to play rugby; I didn't embarrass waiters by calling them out on their gender assumptions; I don't always make space for my female colleagues to speak.

I need to do better.

But what about men? What about us?

The fact that this question even gets asked is testament to Adichie's assertion that we raise girls to "cater to the fragile egos" of men.

Nevertheless, she gives men enough selfish reason to support the cause. She rallies against the very concept of her least favourite word: emasculation.

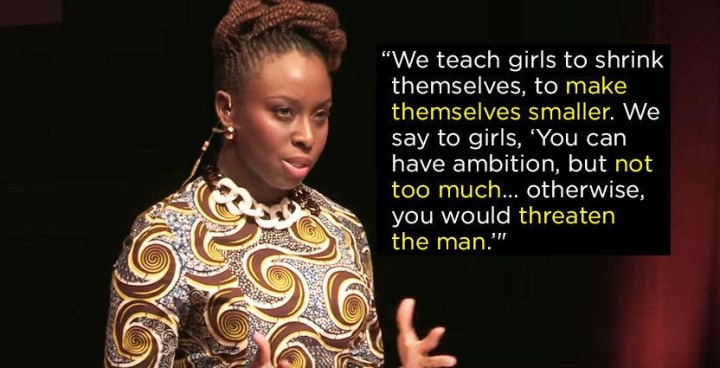

If we can raise boys not to value emotional literacy and candour as valuable, over resources and physical prowess, emasculation ceases to be. They can revel in whatever self they become. And in the absence of the threat of emasculation, girls will no longer need to shrink themselves in tandem to be any less than they are.

Everybody wins.

There is one dominant feeling throughout the whole argument, one which I did not expect from the title: hope.

Against the willful apathy of stock phrases like that's just how it is, she makes perhaps the most memorable point of her whole speech:

Culture does not make people; people make culture.

This is in our hands, if we care.

Intersectionality: the elephant in the room

I love Chimamanda, but this is by no means a perfect feminist essay. It is notably devoid of intersectionality, meaning that only gender is addressed: a vacuum that cannot exist in reality. Every woman is also defined by her sexuality, her cissexuality, her ethnicity, her religion... the list goes on.

The heteronormativity and trans-erasure throughout Adichie's piece certainly stings.

BUT, if we take this essay as a beginner's introduction to feminism, as I have, and not a comprehensive case for intersectional feminism, we can overlook this oversight... can't we?

I'm not sure.

But, I do know this: no feminist essay is an island.

One can only hope that the essay functions as the gateway drug into more developed engagement with feminism as a whole for its young readership. Once this challenging notion is conceptualised, notions of gender-identity and sexuality have a better chance of getting through.

I for one am hopeful about the future: a future where everyone is a feminist.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.