Whenever I'm introduced to someone as 'an English teacher who pursues doctoral research on grammar', I invariably get one of two reactions:

1. 'Oh my! I'd better watch my grammar around you, then.'

2. 'Oh... okay... I'm just going to go over here, now. Nice to meet you.'

Since nobody is interested in my ever-broken heart in the face of pre-emptive rejection, I'm going to dig into the first response, not the second.

Watching your grammar: a history

In the 1960s, American linguist, William Labov, coined the phrase "linguistic insecurity": that universally experienced concern we have about the correctness of our own language use.

About thirty years later, in 1995, language professor at the University of Oxford (and, incidentally, my undergraduate dissertation supervisor), Deborah Cameron, coined the phrase "verbal hygiene": the powerful urge we have to tidy-up and correct the language around us.

So, in the 20th Century, we worried about how we used language and we worried about how everyone else used language.

But it is not limited to the 20th Century. For centuries beforehand, and in what we've seen of the 21st Century so far, this preoccupation with "getting English right" has been ubiquitous. We believe there's such a thing as right English, and so we pursue it dutifully.

What is the right English to use?

Those with a penchant for "correcting" the grammar of others have quite the job on their hands answering this question. Typically, by "correct English", language purists really mean "Standard English".

The uncomfortable truth about Standard English, however, is that it reflects status not quality. Standard English gained its prestige simply by virtue of its origin: the epicentre of England's ruling class, London.

There is nothing inherently superior about Standard English. And there is nothing inherently deficient about any of the non-standard varieties of English.

A common misunderstanding is the belief that non-standard Englishes are simply inferior imitations of Standard English, but the fact is that they are independent, and operate under grammatical structures as consistent and rigorous as Standard English. Look at Labov's work on AAVE (African-American Vernacular English), if you want proof.

So, anything goes?

The logical extension of the above is: so, there are no rules.

That's not quite what I was getting at. I'd say a wiser conclusion would be twofold. Knowing that Standard English is about status not quality, I can recognise that:

1. the vernacular speech of my fellow man is as valid as any other, and warrants no correcting;

AND

2. I have the power to modify my English to suit purpose (I can impress and employer with Standard English, but I don't need to use it on Snapchat).

Yay!

But Standard English has rules, right?

The common standard, Standard English, does indeed have "rules"... but they're not what you'd think of, if I talked about rules of grammar.

Genuine rules of grammar include things like choice of determiners (so we don't give an advice about grammar, or learn some rule) and prepositions (so, we are not interested on English usage, or horrified in mistakes).

The so-called "rules" that most people seem to know (or think they know) about English grammar include:

1. Never end a sentence with a preposition.

2. Never split an infinitive.

I bet you think those are gospel. But, there are two problems with these oft-cited rules for expression (and their many, equally dubious friends):

1. Getting them "right" usually makes the language sound worse.

2. They are based on essentially nothing of merit.

Take the classic example, almost certainly not actually from Winston Churchill:

'Ending sentences with prepositions is the sort of nonsense up with which I will not put'.

Its humour lies, of course, in the linguistic convolution necessary to stick to the "rule" in such an idiomatic expression as this. The other classic example is the the butchered Star Trek rendering: 'Boldly to go where no one has gone before'.

You can see how absurd they sound, right?

In Latin, prepositions are locked to their verbs, and infinitives are single words and thus un-split-able. Latin is dead, though; English, in contrast, lives. English prospers. English, as a largely syntactical rather than inflected language, has infinitely more flexibility with positioning of words. Indeed, there are few places in a sentence where you can't put your adverb, to achieve purpose.

In a bid to make our language more like its Latin "better", some 18th-Century Grammarians invented these rules... and they've stuck with us ever since!

If you need any more convincing, take a look at these two examples:

'Thy pity may deserve to pitied be.'

(William Shakespeare: Sonnet 142)

'[Should we] rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?'

(William Shakespeare: Hamlet)

If our ever-revered bard can split his infinitives and end his sentences with prepositions, then I hardly think we mere rookies deserve criticism for doing the same.

But, wait...

There's more to it.

So... we have some rules that are indeed rules that we should stick to, and we have some rules that are total nonsense that we should fight (when we're not writing job applications, at least).

There's a middle-ground, though: accepted rules that are dying out.

Take the word whom, for example. This is a favourite monosyllabic correction of the language purists: simply interjecting with WHOM whenever a perceived subject/object error is detected.

So it should be WHOM DO YOU LOVE, Bo Diddley!

Calvin Trillin once remarked, 'As far as I'm concerned, 'whom' is a word that was invented to make everyone sound like a butler'.

Despite its sound logic, it has indeed come to sound pompous. We don't need it (the context obviates it, almost always), so it's on its way out.

Language evolves organically and we are impotent fools to challenge it.

In sum, language is going to be okay

For centuries, well-meaning amateurs have longed to "fix" English: both in terms of remedying it and in terms of keeping it stable. Fortunately, despite the inevitable failure of any attempts to do so, the language has been fine. It has coped on its own. It's a tough little cookie.

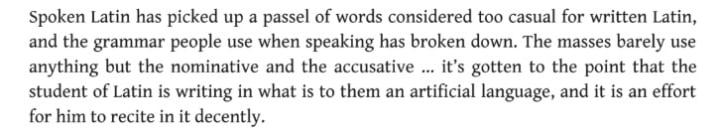

Take this complaint:

The above is from 63AD.

SPOILER ALERT: the language was fine, then.

It's fine now.

It'll continue to be fine.

Your input is not necessary.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.