Sexed but not Sexy

An essay on the representation of pregnant women

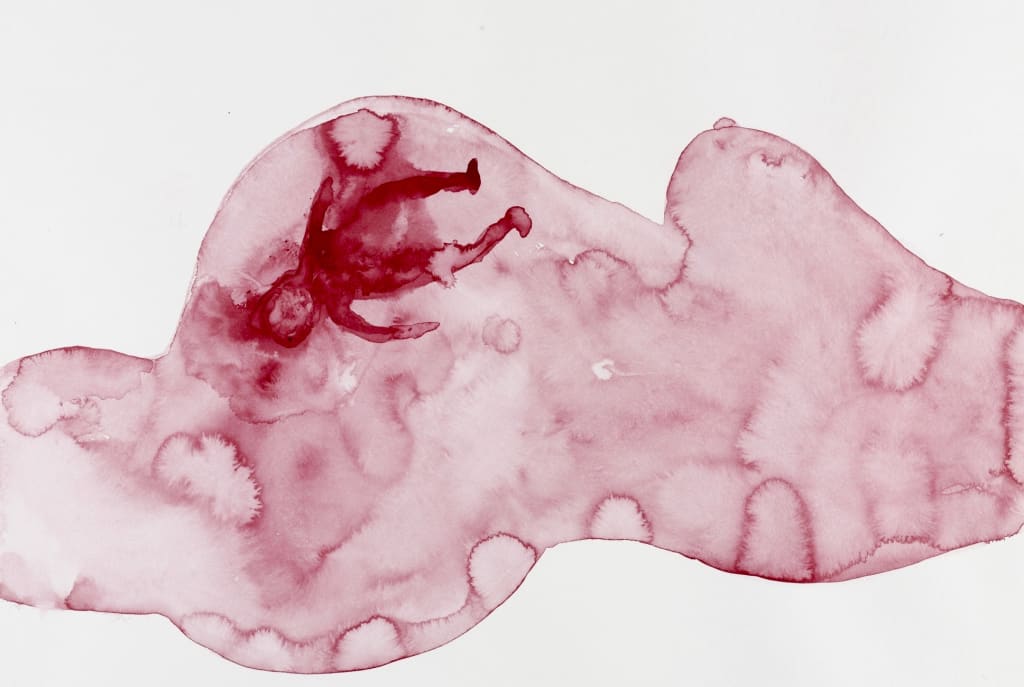

This essay will demonstrate how the pregnant body is both deeply personal whilst being subject to intense public scrutiny. The physical space that a pregnant body occupies in public, and the visibility of something that is deemed to be private, puts growing attention on the expectant mother. A sense of public responsibility for a future citizen (Luce, 1996) forces upon her unwanted opinions and expectations. For the purpose of this essay, the term ‘public’ is treated as interchangeable with the word ‘political’, because it is referring to the everyday politicisation of bodies that makes them public. (Jamie, 2020) For a more in-depth analysis, it will ignore the medicalisation of the pregnant body; the medical surveillance placed on women by midwives and other health professionals. Instead, it will focus on cultural scrutiny, in the form of prying relatives, acquaintances and strangers (Dwyer, 2006) feeling the right to place judgment on the pregnant woman. It will consider the patriarchal environment in which this right to ownership of the female body has been cultivated and worsened by the influence of the media. Drawing upon the routine sexualisation of women in the media, this essay will demonstrate the binary expectations of female sexuality. Within this narrow discourse, it will question the whereabouts of pregnant women. Why it is suddenly unacceptable and wrong for a pregnant body to be ‘sexy’, despite having been ‘sexed’ (Dwyer, 2006). How do pregnant women straddle this ‘Madonna-Whore Dichotomy’ and what implications does this have for the woman and her partner? It will also question this in the context of pornography. Lastly, there will be an examination of how some celebrities have shown both their maternal and sexual pregnant bodies, and in doing so have liberated themselves and other women from the binary categories that they could have fallen in to.

Women face the duality of their bodies being both public and private every day. The privacy of the female body and the bodily processes within it, accompany the female everywhere. Women for instance, are expected to hide the fact they are menstruating as they continue their daily lives, despite perhaps suffering. (Martin, 1987) This is complicated by pregnancy, which is equally intimate but more difficult to hide, meaning that the typically invisible or subjective body is forced to be visible or objective. (Nash, 2006) This is why, when it comes to pregnancy, Robyn Longhurst (2000) argues that public and private should be treated as binary categories. She explains how pregnancy is performative in both public and private space. For instance, health professionals visiting pregnant women in their homes, means that their pregnant space is invaded by an outsider. Equally, public spaces can be invaded by that which is deemed to be private, such as pregnant women wearing bikinis on the beach. This line between public and private results in many ambivalences and contradictions that surround the pregnant body. (Longhurst, 2000)

As pregnant women display an aberration from their normal form, others assumes that they are not expected to follow normal rules of discourse or standards of behaviour. One of these rules is the respect for personal space, which disappears during pregnancy. Uninvited touching is more readily accepted. (Jamie, 2020) Touching a pregnant bump is believed to bring luck, as well as acting as a way of connection to the unborn baby. (Longhurst, 2000) Pregnant bodies hold such public interest and intrusion for a few reasons; the first being their physical difference. People tend to be fascinated by the atypical nature of the pregnant body; a woman who is more protruding, expansive and ultimately, visible than she would usually be. She will inevitably take up more physical space. (Jamie, 2020) There are also risks of bodily leaking such as breastmilk or urine, that should be hidden inside the body. This threatens to happen at any time in a public space. (Longhurst, 2003) The second reason for public engagement is that the pregnant body is carrying a future citizen, over whom the public feel protective. Every move of expectant mothers is scrutinised by the ‘never-resting public eye’. (Neiterman, 2012) This scrutiny is driven by a breakdown in the usual respect for other’s privacy and results in a multitude of expectations that are forced upon the pregnant women. For instance, Longhurst (2000) draws upon a bikini contest that was held in New Zealand in 1998 for pregnant women. She notes the way onlookers reacted to semi-naked pregnant women, with shock and distain. These women, as future mothers, are expected to act in a ‘demure and modest’ manner in the public eye. For this reason, many scholars view pregnancy as a ‘performance’, for which, that the pregnant woman is coerced into playing her expected role. (Neiterman, 2012) Why is it that the pregnant body is made into a public spectacle, but is shamed for acting as one?

To a large extent, the female body is always a public spectacle, accustomed to these levels of public scrutiny. In our sex-obsessed society, mainstream media is saturated in women’s appearance and sexuality. (Flood, 2009) Women construct their own self-identity relating to ‘sexuality, beauty, body image and appearance’ through the gaze of others, particularly men. (Nash, 2006) Seeing that our culture is dominated by naked female bodies, commodified and used as marketing tools, women get a clear message of what they are supposed to be. The question becomes, with such sexually charged imagery of women virtually everywhere we turn, where is the inclusion of pregnant bodies? In the media’s narrative, pregnancy equates to asexuality and unavailability. The maternal body is incompatible with the sexual body, and the thought of combining them is somewhat disturbing. (Dwyer, 2006; Zwalf et al., 2020) A woman’s ‘ornamental function’ is expected to shift when she falls pregnant from being a seducer to being a producer. (Charles and Kerr, 1986) This shift encompasses not only the woman’s body, but the way she presents it and dresses it too. She must embody her asexual state. This fits into the normal narrative that surrounds gendered sexuality whereby men are sexually active and women passive. (Kahalon et al., 2019) When considering women in a sexual light, conventional societal attitudes dictate that they fall into two categories: virgins or whores. (D’Emilio & Freedman, 1988; Tiefer, 2004), the latter being the preferred category; women should be desired, but not desiring. (Gavey, 2005; Tolman, 2002) This notion was termed the Madonna-Whore Dichotomy by Sigmund Freud. (Freud, 1905; 1912) These categories are complicated by pregnancy, which manifests the paradox that we value children but we don’t value reproduction. In our pro-natal society, a child is welcomed and therefore the mother is celebrated. She is in her natural state of pregnancy; moral and saintly. However, the mother also acts as a visual reminder of sexual intercourse. She is tainted by the act of sex and is therefore the embodiment of a whore. (Jamie, 2020) Thus she perfectly straddles this dichotomy. These culturally constructed categories are problematic for some expecting fathers. Freud (1905; 1912) suggested that some men are unable to maintain a sexual attraction to the mother of their child. These men develop the same feelings they had for their own mothers, a feeling of respect and admiration, but also sexual repulsion for their partner. They are unable to understand a women’s sexuality as both ‘tender’ and ‘sensual’ at the same time. (Kahalon et al., 2019)

It is interesting to consider the position of pregnant women within pornography; material that is specifically designed to sexually arouse its audience (Malamuth, 2001) Can women in this role be sexy, despite having pregnant bodies that we intentionally don’t want to find sexy? The difference between mainstream media and media in the form of pornography, is that the former excludes abnormal bodies whereas the latter profits of them. The porn industry creates specific genres that trade on stereotypes (Elman, 1997), such as race, age and class; or even disability and pregnancy. These niches can then be ‘superimposed on the gender or power dichotomy’. (Hardy, 1998) Rebecca Huntley (2000) conducted a study into the representation of pregnant bodies in various mediums, that each showed the maternal body as a sexually active one. The first being a Playboy magazine that featured actress Lisa Rinna, who was pregnant at the time. The second was a hard-core pornographic film involving a girl performing various sexual acts during her pregnancy. The last was an informative manual that had a section devoted to sex and sensuality during pregnancy. Interestingly, despite how heavily the female bodies are fetishized by the magazine and film, Huntley describes how they still heavily imply maternity. They dance in between sexiness and motherhood. The magazine captures Rinna wearing her wedding ring; she is sexy within the boundaries of her relationship and therefore, love and motherhood are wrapped up in her pornification. Similarly, the film closely follows the storyline of pregnancy, focussing on the girls growing stomach and the introduction of breast milk as a sexual fluid. Usual porn creates an idealised woman with tendencies of a ‘nymphomaniac’ whilst remaining virginal and submissive. (Huntley, 2000) Pregnancy further complicates this; the confusion of ‘sluttishness and maternity’ is a continuation from the Madonna-Whore Dichotomy.

The black and white extremes laid out of being a sexualised woman versus being an asexual pregnant woman, and being a whore versus being a virgin, were challenged by the media towards the end of the 20th Century. The emergence of glamorous celebrity displays of pregnancy began to change the discourse on it dramatically, and the bridge between sexuality and maternity (Dwyer, 2006) began to close. Many scholars attribute the beginning of this change to the feature of actress Demi Moore posing for a Vanity Fair cover in 1991 covered in diamonds, pregnant and naked. (Nash, 2006) Modern celebrities followed in this trend, whereby having these photoshoots sexualises their pregnant bodies. (Zwalf et al. 2020) This helped to shape a new visibility that pregnant women had not previously received. Perhaps a more interesting example is of Britney Spears’ pregnant experience. Having been constructed by the media as a sex icon since her early career and teenage years, she was accustomed to routine scrutiny in the public eye. Her transformation during pregnancy therefore, can be used as an interesting case study regarding the paradox of the public and private pregnant body. Spear’s body had long before been claimed as public property. Fitting into the Western ideals of slenderness and sexiness, she was seen as one of the ‘bad sexual girls of pop’. (Jackson and Vares, 2015) She continued to direct this hypersexualised lens onto her pregnant body, (Lowe, 2003) posing for Elle magazine in 2005, showcasing herself as a ‘sexy mother’. (Nash, 2006) She, amongst other celebrity mothers turned pregnancy into a fashion statement. (Longhurst, 2005) The public discourse started to focus on fashionable bumps and desirable maternity wear. Previously hidden under a limited range of floral, modest and billowy dresses, (Nash, 2006) the pregnant body began to be celebrated in new trends where it was acceptable to show flesh as an expecting mother. This was replicated on the Highstreet, with the growth of a specialised maternity clothing market, such as ‘Blooming Marvellous’ and ‘Mamas and Papas’. (Earle, 2003) She also addressed the topic ‘on motherhood, marriage and her sex drive’, which directly straddles the Madonna-Whore Dichotomy. Having a ‘hot sex life’ is incompatible with the images of a sacred Virgin mother often associated with pregnant bodies. (Nash, 2006) This was a topic that was previously absent from popular media. Marrying pregnant fashion with pregnant sex life, are brands like ‘HOTmilk’, lingerie that is advertised as celebrating the ‘sexy, sensual woman inside the loving mother’. (Tyler, 2011)

It is also necessary to consider the repercussions that this societal shift in attitudes has on pregnant women. Pregnancy received newfound attention, never before having been ‘so visible, so talked about and so public.’ (Tyler, 2011) Following Moore and Spears along with other sexy celebrity mothers, the media narratives began to progress. Magazine covers worshipped the ‘svelte figure, high-income yummy mummy’. (McRobbie, 2006) This returns to Rinna in Playboy, as she flaunted her contained, toned body with unaffected skin that shows ‘no evidence or stretch marks or fluid retention’. (Huntley, 2000) There became a new breed of mother who could regain her pre-pregnancy body rapidly after giving birth and matches her designer baby to her own designer outfits. The problem with this new ideal of femininity and beauty is that it is unattainable. Is there a middle-ground between the nonsexual, unglamorous and the perfect-bodied, elegant model of motherhood?

In conclusion, this essay has attempted to show how perceptions of women’s sexuality and motherhood are embedded in gender power structures. (Kahalon et al., 2019) The paradoxes of the pregnant body are mostly constructed by the male gaze. Whilst men primarily link the female body to sex, as it is presented everywhere in our culture, they struggle to link the pregnant body with anything other than motherhood. This is why an outwardly sexually active body must present itself as asexual. (Bailey, 2001) This sexual script (Bay-Cheng, 2015) takes away many female liberties, the main one being the right for them to feel sexy; in the privacy of their own bedrooms or in the public eye of busy streets. The last two decades have seen a shift in public expectations of pregnant bodies, demonstrated by the latest fashions, (Earle, 2003) and the emergence of social media, which allows celebrities to record their pregnancies even more openly. Today’s pregnant celebrities boast their ‘yummy mummy’ status (McRobbie, 2006), priding themselves on their looks and sex appeal. This rejects the assumptions that their bodies should be abject and asexual, (Betteron, 2006) as women take ownership of themselves. However, it also constructs a dangerously unattainable maternal figure. (Betterton, 2006) More research is required into the majority of mothers, who occupy the space in between these two ideals.

Bibliography

Bailey, L. (2001). Gender shows: First-time mothers and embodied selves. Gender and Society, 15(1), 110-129.

Bay-Cheng, L. Y. (2015). The agency line: A neoliberal metric for appraising young women’s sexuality. Sex Roles, 73, 279–291. doi:10.1007/s1119

Browyn, C. (2006). Neo-Institutionalism, Social Movements, and the Cultural Reproduction of A Mentalité: Promise Keepers Reconstruct the Madonna/Whore Complex, The Sociological Quarterly, 47:2, 305-331, DOI: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2006.00047.x

D’Emilio, J., & Freedman, E. B. (1988). Intimate matters: A history of sexuality in America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Dwyer, E. (2006). From private to public bodies: Normalising pregnant bodies in Western culture. In Nexus: Newsletter of The Australian Sociological Association, 18(3) pages pp. 18-19, The Australian Sociological Association (TASA).

Earle, S. (2003). “Bumps and boobs”: Fatness and women’s experiences of pregnancy. Women’s Studies International Forum, 26(3), 245-252.

Elman, R. A. (1997). Disability pornography: The fetishization of women’s vulnerabilities. Violence Against Women, 3(3), 257-270.

Flood, M., (2009) ‘The Harms Of Pornography Exposure Among Children And Young People.’ [ONLINE] Available at: http://(www.interscience.wiley.com)[Accessed December 1 2020]

Freud, S. (1905). Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie [Three essays on the theory of sexuality]. Berlin, Germany: Leipzig und Wien.

Freud, S. (1912). U¨ ber die allgemeinste Erniedrigung des Liebeslebens [The most prevalent form of degradation in erotic life]. Jahrbuch fu¨r Psychoanalytische und Psychopathologische Forschungen, 4, 40–50

Gavey, N. (2005). Just sex? The cultural scaffolding of rape. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hardy, Simon. (1998). The Reader, the Author, his Woman and her Lover: Soft-core Pornography and Heterosexual Men. London: Cassell.

Huntley, R. (2000). ‘Sexing the Belly: An Exploration of Sex and the Pregnant Body’, Sexualities, 3(3), pp. 347–362. doi: 10.1177/136346000003003004.

Jamie, K. (2020) 'The Ambiguity of the Pregnant Body' [Recorded Lecture] SOCI3557: Sociology of Reproduction and Parenthood. Durham University. 20th October. Available at: http://duo.dur.ac.uk (Accessed: 20th October 2020)

Jackson, S. and Vares, T. (2015). ‘‘Too many bad role models for us girls’: Girls, female pop celebrities and ‘sexualization’’, Sexualities, 18(4), pp. 480–498. doi: 10.1177/1363460714550905.

Kahalon, R. et al. (2019) ‘The Madonna-Whore Dichotomy Is Associated With Patriarchy Endorsement: Evidence From Israel, the United States, and Germany’, Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(3), pp. 348–367. doi: 10.1177/0361684319843298.

Kaplan, H. S. (1988). Intimacy disorders and sexual panic states. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 14, 3–12. doi:10.1080/ 00926238808403902

Lowe M. (2003). Colliding feminisms: Britney Spears, ‘tweens’ and the politics of reception. Popular Music and Society 26(2): 123–140.

Longhurst, R. (2003). Breaking corporeal boundaries: Pregnant bodies in public places, in John Hassard, Ruth Holliday (editors) Contested Bodies. London: Routledge.

Longhurst, R. (2000). ‘Corporeographies’ of pregnancy: ‘bikini babes’. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 18, 453-472.

Longhurst, R. (1999). Pregnant bodies, public scrutiny: ‘Giving’ advice to pregnant women. In E. Kenworthy Teather (Ed.), Embodied geographies: Spaces, bodies and rites of passage (pp. 78-90). London: Routledge.

Luce, J. (1996.) 'Visible Bodies: Revealing the Paradox of Pregnancy' National Library of Canada

Malamuth, N. (2001) ‘Pornography’, pp. 11816–21 in N.J. Smelser and P.B. Baltes (eds) International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Martin, E. (1987). The Woman in the Body. Boston: Beacon Press.

McRobbie, A. (2006). ‘Yummy Mummies Leave a Bad Taste for Young Women’, The Guardian, 2 March, online at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2006/mar/02/ gender.comment.

Nash, M,. (2006). 'Oh Baby, Baby: (Un)Veiling Britney Spears' Pregnany Body' [ONLINE], Bodies: Physical and Abstract Vol 19. Available at: <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.ark5583.0019.002>

Neiterman, E,. (2012) 'Doing pregnancy: pregnant embodiment as performance' [ONLINE], Women's Studies International Forum. pg. 372-383 Available at: <www.elsevier.com/locate/wsif > [ACCESSED 18 December 2020]

Betterton, R,. (2006). ‘Promising Monsters: Pregnant Bodies Artistic Subjectivity, and Maternal Imagination’, Hypatia, vol.21, no.1, pages 80-100.

Rose, N. (1990). Governing the soul: The shaping of the private self. London: Routledge.

Tiefer, L. (2004). Sex is not a natural act and other essays (2nd ed.). Boulder, CA: Westview Press.

Tolman, D. L. (2002). Dilemmas of desire: Teenage girls talk about sexuality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tyler I. (2011). Pregnant Beauty: Maternal Femininities under Neoliberalism. In: Gill R., Scharff C. (eds) New Femininities. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230294523_2

Zwalf H, Walks M, Mortenson J,. (2020,). Mothers, Sex and Sexuality. Ontario: Demeter Press.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.