What Has Been the Federal Reserve’s Biggest Policy Misstep?

Fed Leaves Rates Unchanged

Without a doubt, it was waiting too long to raise its policy interest rate (e.g., the federal funds rate) until inflation rose to unacceptable levels. Nonetheless, what eludes most Fed critics, who seem to believe this is the Federal Reserve’s most significant blunder of all time, is that this has happened many times before. Although making the same mistake more than once is not a valid defense, we seek to set the record straight on this issue.

Nonetheless, what eludes most Fed critics, who seem to believe this is the Federal Reserve’s most significant blunder of all time, is that this has happened many times before. Although making the same mistake more than once is not a valid defense, we seek to set the record straight on this issue.

Still, such factors may continue to weigh heavily on the Fed and may be one reason why the Fed left its policy rate unchanged on June 12, 2024, after observing a better-than-expected May 2024 Consumer Price Index (CPI) report. Headline and core prices (excluding food and energy) rose at a diminished 3.3% and 3.4% yearly growth pace, respectively.

Nonetheless, the Fed will focus on its preferred inflation gauge, the core Personal Consumption Deflator (PCE), excluding volatile food and energy components. The Fed considers the PCE a superior measure because the weights of the individual components included in the index will vary depending on the consumer's purchasing habits. That means that if two competing components are included in the index, the weights of each good or service will depend on the consumer's purchasing patterns. If consumers shift demand from one product to another, the weight of that component will increase and provide a better gauge of underlying inflation.

Given the cards we have been dealt, the issue that needs to be settled is how quickly inflation has dropped (using the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge) across prior monetary tightening cycles (defined from the start of an increase in the federal funds rate until the Fed lowers the rate) since the mid-1960s to conduct a non-biased assessment of the current monetary tightening cycle.

Some Say, It’s All About Timing

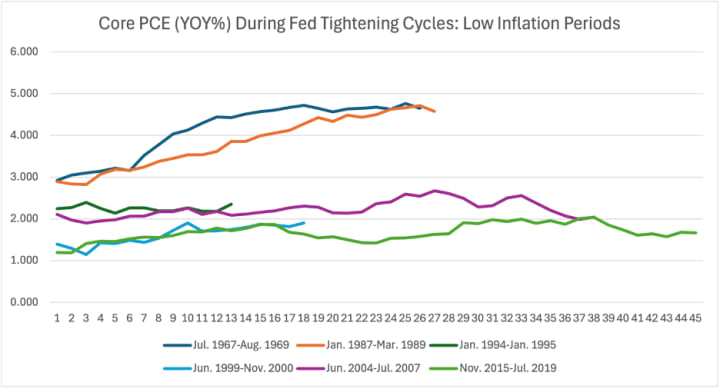

The Federal Reserve has raised interest rates and maintained a restrictive monetary stance during low and high inflation periods. To review the Federal Reserve’s performance across tightening cycles, we separate these policy moves as occurring during low and high inflation periods.

Low Inflation Rate Periods

Although praising the Fed for embarking on a restrictive policy stance when inflation is low may be tempting, a meticulous assessment requires tracking inflation through the duration of the Fed-tightening cycle. That means if the Fed gets a valuable head start on the tightening cycle but experiences rising inflation during the tightening cycle, we will judge the outcome as being largely unsuccessful.

Within the low inflation category, we include periods in which the Fed began to raise the federal funds rate when the core PCE (the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge) yearly growth rate was rising by 3.0% or less. The results under this scenario were mixed.

In four periods, we ruled the Fed’s strategy as relatively successful as the inflation rate remained at or near the Fed’s desired 2.0% inflation target throughout the cycle. However, during the 1967-1969 and 1987-1989 tightening periods, the core PCE inflation rate moved sharply higher during the Fed’s tightening cycle, thereby generating disappointing results!

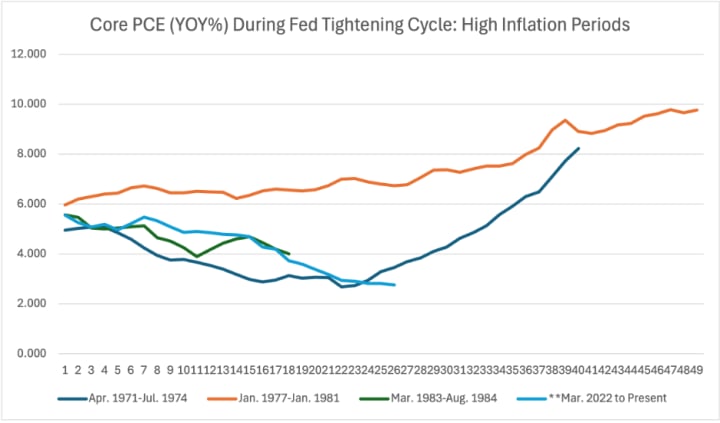

High Inflation Periods

Within this category, we include four monetary tightening cycles in which the Fed began to raise the federal funds rate after observing the core PCE inflation rate rise by 5.0% or more. It is easy to argue that given an inflation target growth rate of +2.0%, the Fed’s biggest blunder to date was waiting too long to raise its policy rate in March 2022. However, if one were to level that criticism, one must admit that this policy error was committed in three other historical periods!

The least successful tightening cycle was from 1977 to 1981 when the Fed started raising rates with a core PCE inflation rate rising by 6.0%. Throughout the cycle, the core PCE inflation rate increased when Fed Chair Arthur Burns was at the helm, followed by Fed Chair G. William Miller, who presided at the Fed from March 1978 to August 1979. Chair Paul Volcker took over the Fed after G. William Miller was ousted. During his early years, Volcker struggled to bring inflation down, and it was not until the second half of his tenure that he successfully slayed the inflation dragon!

Although we readily acknowledge that the Fed should have started raising rates sooner than March 2022, we tracked inflation's path relative to prior tightening cycles. Using this criterion, the Fed’s performance during the latest cycle has been relatively successful.

Taking A Deeper Dive into Some of the Fed’s Significant Policy Experiences

Between July 1967 and August 1969, the Federal Reserve maintained tight monetary policy with an elevated federal funds rate. However, after Fed Chair, (William Chesney Martin) admitted that its restrictive monetary policy failed to arrest inflation pressures, the Fed eased monetary policy towards the latter part of the Fed Chair’s tenure, which ended in January 1970. In fact, from August 1969 to February 1971, the Fed lowered the average federal funds rate from 9.2% to 3.7%, as the core PCE inflation rate rose from 4.6% to 5.0%. Interestingly, market pundits chastise the Fed for even considering rate cuts with a core PCE growth rate of 2.8%.

To be sure, the message we hear most often is that the Fed doesn’t want to repeat the errors that the highly-respected inflation fighter Paul Volcker made during the early years of his tenure. Fed Chair Volcker guided the federal funds rate lower from an average of 19.1% in January 1981 to as low as 8.5% by February 1983, only to be forced to raise rates again to combat inflation. Critics often forget that the federal funds rate was lowered in 1981 when the core PCE yearly inflation rate was rising at a staggering +9.8% yearly pace compared to its latest reading of +2.8%. If the Federal Reserve were to lower the federal funds rate today with a core inflation rate near 10.0%, I am confident that the heads of many economy watchers would explode!

However, in defense of Chair Volcker, with a federal funds rate of 19.1% and a core PCE inflation growth rate of 9.8%, there may have been room for a slightly lower federal funds rate. Nonetheless, lowering the federal funds rate below the underlying inflation rate may have been too aggressive, which required Volcker to pivot and restart another hiking cycle after previously lowering interest rates.

In March 1989, Fed Chair Alan Greenspan eased monetary policy slightly by lowering the average federal funds rate from 9.85% in March 1989 to 8.5% in December 1989 despite an underlying core PCE yearly growth rate of +4.6% in March 1989. However, this strategy was still restrictive since the spread between the federal funds rate and core PCE remained positive even as the Fed modestly lowered the federal funds rate.

Such actions proved that the Fed could lower interest rates and maintain a restrictive policy stance if the federal funds remained above the underlying inflation rate. This policy gambit worked well for Greenspan as the yearly growth in core PCE dropped from 4.6% in March 1989 to +3.7% in December 1989. Back then, growing inflation at this pace was considered a successful outcome, while a 2.8% inflation rate today is viewed as a policy flop.

Summary and Concluding Thoughts

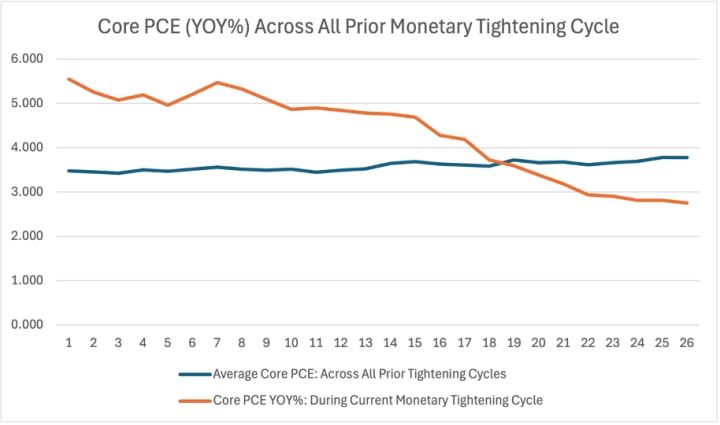

Our nonpartisan review of all the Fed's previous monetary actions dating back to the mid-1960s reveals that the Fed has done a relatively good job managing the latest monetary tightening cycle compared to prior ones where the results could have been better.

Comparing the average core PCE across low and high inflation periods to the current monetary tightening cycle, we find that inflation has dropped much faster than all the previous monetary strategies since the mid-1960s. Sadly, this has been lost in many market discussions, as the consensus believes the Fed performed poorly in the current cycle.

While we readily acknowledge that the Fed erred by waiting too long to begin raising the federal funds rate, our results reveal that in some periods where the Fed raised sooner, it was unable to push inflation lower, thereby squandering any advantages it may have gained from preemptively raising its policy rates.

About the Creator

Anthony Chan

Chan Economics LLC, Public Speaker

Chief Global Economist & Public Speaker JPM Chase ('94-'19).

Senior Economist Barclays ('91-'94)

Economist, NY Federal Reserve ('89-'91)

Econ. Prof. (Univ. of Dayton, '86-'89)

Ph.D. Economics

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.