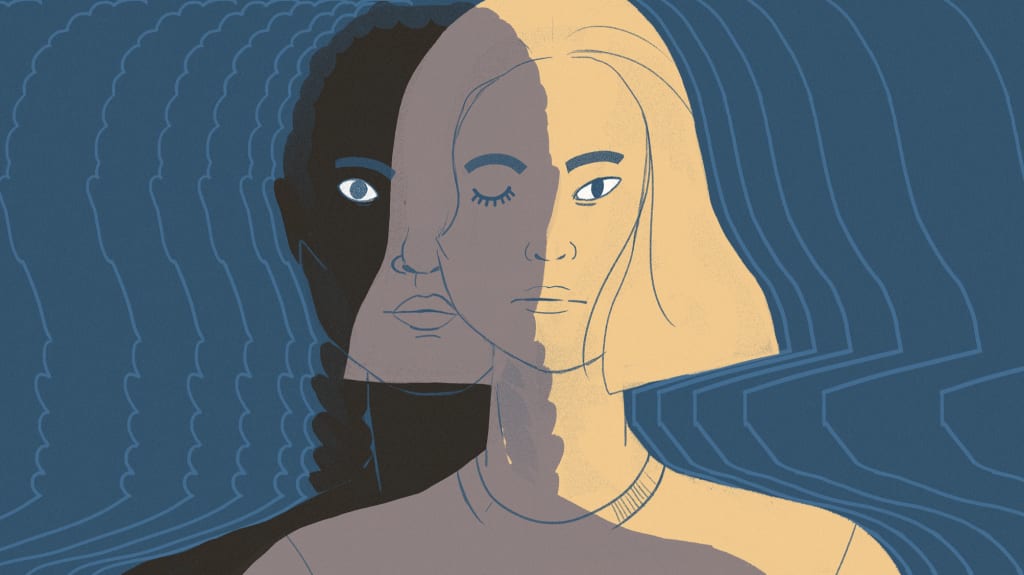

Cultural Appropriation and Racial Identity

Between African American and Brown Communities

Among many things, the concept of identity is soiled in history, culture and socio-economic power. As second-generation immigrants of the Western world, these aspects about ourselves begin to blur. Thrusted into a world of a different culture, history and hierarchy of power, it becomes the responsibility of society and the individual to sort themselves among these lines. But when our concepts of identity begin to blur, so do our notions of right and wrong-- specifically, our ideas of what constitute as appropriate facets of our identity. As a result, we become lost in a cycle of taking on the different cultures and identities we are exposed to, mindless of the consequences that stem from that process. Consequently, not only does one stray further away from their own cultural identity, but they manage to take on facets of cultures they have no right taking part in, perpetuating the prevalence of cultural appropriation.

It is this issue of identity that has become so intertwined with today’s perplexing case of cultural discourse. On one end, one must devote their whole self to the heritage and culture they were born into, whilst growing up surrounded by differing cultures and values. On the other, one must throw away their entire innate heritage and culture to become accustomed to the state of Western culture. Those in the middle continue to move from one end to the other, struggling to develop a core sense of self in the process. This inner discourse is prevalent within the youth of many second-generation immigrants and calls to question the socially and politically correct steps required in order to avoid, in this case, cultural appropriation.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: I was asked to answer the dilemma regarding the appropriation of African American culture done so by the Brown community. While this is a large dilemma to unpackage, I've tried my best to understand it by tying it back to the concept of identity. This is an attempt to bring both sides into the conversation, but please note: this is not an attempt to justify, but rather prove, the wrongful intentions behind the cultural appropriation of African American culture, while drawing attention to a greater dilemma regarding identity.

On the concept of identity, it is important to mention that as second-generation immigrants coming from a wide array of different cultural backgrounds, there are no significant cultures to identify in that currently exist solely in the Western world. The cultural facets that are brought from our homelands exist solely from there. Regarding the Western world, one has no pre-existing culture to resonate with, and must resort to assimilating oneself into the cultures at-hand. Predominantly speaking, the only cultures that have had centuries to develop in the Western world, whether it be through power or oppression, surround those regarding the white, African American and South American communities. For the Brown community, we have yet to establish a culture and community that belongs solely to the Western world. This does not give second-generation youth the right to appropriate facets of another community’s culture, but rather, it gives us an opportunity to form and develop a culture of our own to identify with.

Because identity is so intertwined with one’s culture, outsiders do not warrant the right to appropriate another community’s culture. Not only can this warp one’s sense of identity, but it destroys the foundation of identity that’s associated with the members of that community; in this case, it is the African American community. When members of the Brown community assimilate themselves into a community that they have no cultural or historical ties to, it puts into question what constitutes the identity of those involved. Take Rachel Dolezal, for example, who self-identified as African American despite her white heritage in 2015: “By choosing to identify as ‘transracial’, Dolezal and others like her insult members of marginalized groups who cannot ‘choose’ to be white and be privy to the privileges that come with whiteness… many of her critics (both white and African American) shamed her for co-opting an identity that was not hers” (Balanda, 2020). This misconstrued concept of identity allows for the assimilation or appropriation of another culture with a disregard for the notion of privilege, social/political standing and power. Second-generation immigrants and people of colour neither have the right or privilege to indulge in cultural appropriation. If it is identity that one is looking for, assimilating another community’s culture will not only bring on offence and discrimination, but it will also stray one further away from a true and genuine sense of self.

This extends to matters of fashion, language, tradition, music and art. In her novel White Negroes: When Cornrows Were in Vogue ... and Other Thoughts on Cultural Appropriation, Lauren Michele Jackson goes on to explain that “Fascination with African American bodies and appearance has been commonplace since ancient times, and many people manifest this obsession by trying to appear as African American… while society found African American people a source of attraction, they had no desire to equally integrate them into dominant society” (Jackson, 2019). With this in mind, it is not only at “the hands of white men” that we see this discrimination continue. Many members in the Brown community play a prevalent role in taking on aspects of African American culture and appearance, while neglecting to address the racism that’s so integrated in our culture: “From dabbing to ‘squad’, collards to streetwear, babywearing to vogueing to EDM, to jass to ‘lit’ to ‘slay’ to durags… it is destiny that African American insights will be grasped, passed along from edgy to not-so-edgy, till’ everyone joins in, even the racists” (Jackson, 2019). Racism towards the African American community is heavily present throughout Brown culture and to dismiss it is as harmful as it is ignorant. As Kamal Al-Solaylee states in his novel Brown: What Being Brown in the World Today Means (to Everyone), “I had thought myself as light-skinned than most of them. They were dark-brown, couldn’t these racists tell the difference?” (Al-Solaylee, 2016). Furthermore, he goes on to say that “being of a lower class made it acceptable to be of darker skin” and that he’d “often take advantage of being perceived as not African American” (Al-Solaylee, 2016). The stigma surrounding African Americanness in Brown culture is not of the positive kind. There are negative undertones, accompanied by degrading slurs and remarks, that regard those of darker complexions and this is still normalised today. Al-Solaylee goes on to explain that “If you’re brown, it's hard to deprogram yourself from thinking such seemingly superficial but nonetheless existential questions as: Am I too dark? If I get darker, will I lose my social position?” (Al-Solaylee, 2016). Along with these superficial questions, the use of slurs towards the African American community is commonplace in Brown cultures. Our hierarchy of skin tones dictate the kind of respect and commodity that's given towards an individual. With my own eyes, I’ve seen the stereotypes and prejudices that people of my own community place and normalize on African Americanness. All the while, second-generation youth find it appropriate to accessorize facets of African American culture. It sickens me to hear people of the Brown community normalize the use of the ‘n’ word as a part of their vocabulary. It’s unsettling to see facets of African American culture being used as accessories to accommodate a false sense of self. The Brown community is not excluded from this discussion and have just as much to do with it as the white community.

Whether you participate directly or are a by-stander to this, we are inevitably responsible for taking accountability. Cultivating a Western culture for the Brown community can take decades, or longer, as it did for every other community established in the West, but it is necessary if we are to dismantle cultural appropriation. It involves a struggle between heritage and prevailing culture, but to create our own position in Western culture can bring on a true sense of community and identity. Instead of relying on and invading the cultures that another community derives their sense of identity from, second-generation immigrants have a chance to foster one that is intrinsic to them and their community. Rather than being divisive, this approach could bring on a greater sense of belonging, setting the stage for future generations to come. Rather than relying on culturally appropriated facets of identity, we can collectively form a culture that is authentic to the West, freeing ourselves from an array of cultures that don’t necessarily belong to us. It is in our hands to change the thought patterns and behaviors regarded towards dark complexion, and to destroy the biased, false conceptions held towards African Americanness. It is in our hands to form new ideas regarding race and identity, and to dismantle the prevalent racism that exists within our culture. It is in our hands to take accountabilities for all the harm that’s already been caused. We’ve never had the right to participate in the cultural appropriation and discrimination of African American culture and it is on the Brown community to discuss what next steps must be taken in order to dismantle this system of oppression.

For more information:

https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1943&context=student_scholarship

Jackson Lauren Michele. White Negroes. Beacon Press 2019. INSERT-MISSING-DATABASE-NAMEhttps://api.overdrive.com/v1/collections/v1L1BcAAAAA2A/products/bfeb6771-2fa8-451e-85d0-472cd0a0dd66. Accessed 14 Nov. 2022.

Al-Solaylee Kamal. Brown : What Being Brown in the World Today Means (to Everyone). First Canadian ed. HarperCollins Publishers 2016.

About the Creator

Aathavi Thanges

Disposing my thoughts one page at a time

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.