What Becomes of Pieces

How I launched and sold a clothing brand during a pandemic by cutting up sweatshirts.

I started cutting up sweatshirts for more than one reason but a big one was that I was laying on the floor a lot. I drank so much grapefruit juice that I passed out on an eastbound Long Island Rail Road train and afterwards a bystander said he thought I had died. I had no idea there was a limit to the amount of grapefruit a person can drink, and wouldn’t learn about the adverse effects of mixing Adderall and acidic juices until later that day after minutes of WebMD research.

I boarded the LIRR from Penn Station a few hours after learning that Nathan was sleeping with the type of person who has never finished a book and cries when nothing is about her. What’s worse, I found this out by reading a really distasteful iMessage on his MacBook, which in my defense, should have been password protected and in the closed position. What’s worst of all is that her name was Moa, which sounds less like a name and more like a sound to me.

Nathan had let me know often over the course of our relationship that he only kept in touch with Moa because he liked her dog, which is all the more embarrassing for him, since I know that she has a poodle.

Nathan could never help but say what he was thinking despite who was around or how ignorant he sounded, which had the effect of convincing me that whatever doubts I had about him and Moa were unfounded. I considered him incapable of lying because of the inherent outrightness of his personality, so I didn’t take it very seriously when he showed me too many pictures of Kiwi Frankencop the ugly poodle, or when he started taking food too seriously out of the blue. Once I came over to his apartment without announcing myself first and he was baking pretzels from scratch. This wouldn't have been so unacceptable to me if he had established himself as someone who loved baking, or pretzels, but I knew that he loved neither.

I would say things like “So how about that Moa girl?” and he would say, “What about Moa?” to make me feel unreasonable, and I would respond, “I don’t like her.” So you can’t say I didn’t have my wits about me.

Fundamentally, Nathan Kempski and I were two tragically independent people, neither of us any less than the other, which was a consequence of having never learned any other way to be. We never considered each other. Neither of us knew how to bear the weight of adopting someone else’s self sufficiency, and at the time, we were too similar to even realize it. This exercise in mutual devastation was not as inoculating as I needed it to be in order to move on without thinking very hard about his betrayal. None of this is as simple as it sounds, but one must start somewhere.

The closure I should have earned from ending this somewhat unsavory relationship was clouded by an embarrassing jealousy. Over the past year, the things I liked, the places I went, the people I hung out with - all of these things had been repossessed by Nathan’s things, places and people. I was certain, however, that I had taken possession over none of his life. Nothing had changed for Nathan because Nathan hadn’t changed, I was the one who would have to readjust. While this should have made me angry, it mostly left me jealous of the power he had.

Earlier the same week, I had been laid off from my job as a model agent on account of the COVID-19 pandemic. A lot of people were. But of course it was much worse when it happened to me, because it happened to me. It was Friday the 13th - once a historically lucky day for me personally, but now just an anniversary of the beginning of COVID-19 related lockdown mandates in New York and across the country.

When people asked, I explained that my being laid off from the modeling agency was a "blessing in disguise.” I was good at my job, someone pretty high up at the agency was supposed to have said at some point, but I thought myself too creative to work for someone else for much longer. I had ideas of my own and the type of frantic compulsion for success that office environments hardly ever nourish.

I put my furniture in a storage unit in Brooklyn on the last Saturday in March and on the first of April I took a train from Penn Station to Port Jefferson, Long Island. Long ago I had lost the key to my parent’s house, mainly because I never intended on coming back, but also because every time I called my Dad over the past year and a half, he said things like “I'm in Taipei” at the “opening of a new Planet Hollywood.”

There I was, a tenured New Yorker, an expert on alternate routes to the Hamptons, stuck somewhere between the Greenlawn and Northport stops of a peak hour commuter train with low blood sugar, and a new skepticism toward the existence of unconditional love. I was becoming more fearful by the second that if I did nothing I loved for much longer, I would be forced to do something I hated, like manage a Zara in Bryant Park. I hadn’t read “The Artist’s Way” for nothing.

I was only 27 but already the constant lingering feeling of time running out had started to keep me up at night. The awareness that my life exhibited some sort of deficit of intention was always somewhere at the front of my mind, no matter where I was or what I was doing.

It wasn’t that I couldn’t have saved the life I had established over the past 10 years in New York. It was instead my own conviction that to stitch a life together, which had previously been broken into a hundred pieces, would leave me in a constant wake of my own anxieties - that pretending to fix myself in a place where my past was already public information would be the equivalent of putting Frankenstein together again.

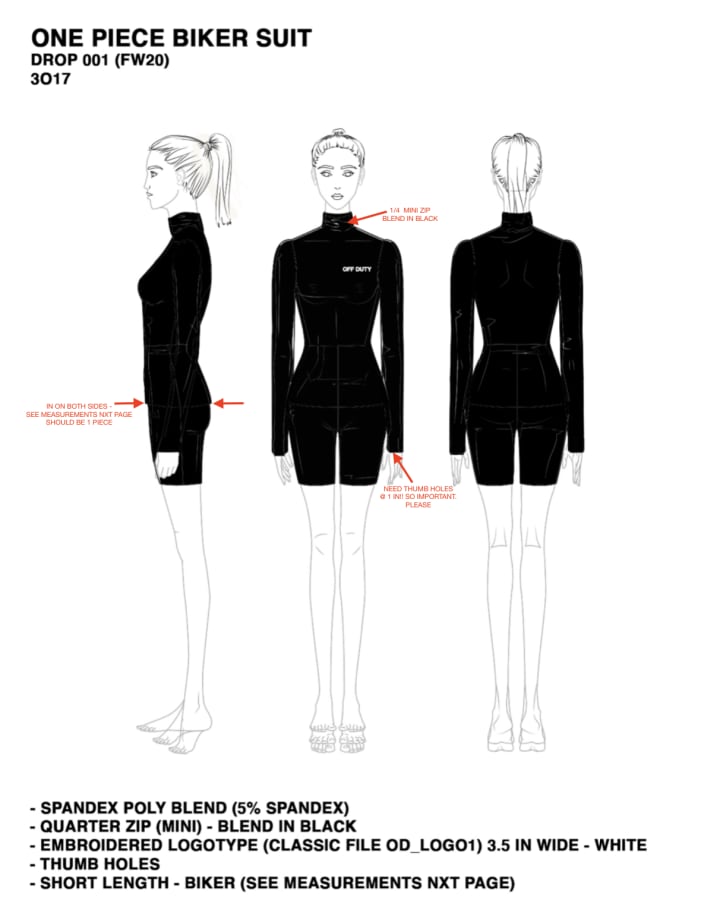

I began thinking about creating clothes in 2018, though who knows how long I’d been thinking about it or visiting it in my mind before then. I had made samples of deconstructed sweatshirts with a blocky OFF DUTY logo printed on the chest and brought them to the agency for models we worked with to try on and wear. Some girls even bought the hoodies from me, but that was the extent of Off Duty's reach as a label.

The phenomenon of street style as uniform fascinated me on account of its duality. The phrase “Off Duty” garnered visions of models exiting Parisian fashion shows in full hair and makeup paired with a tracksuit and sneakers, or the girl walking down Mulberry Street wearing an oversized sweatshirt with patent leather knee high boots - the girl whose effortlessness was what everyone else wanted for themselves. This balancing act between high and low also meant that Off Duty girls never had to resign themselves to either end of the spectrum exclusively. They could be both frivolous and uncomplicated, boisterous and intelligent, forthright and unassuming, or refined and playful - they were a mirror for the nuanced world that I was having so much trouble making sense of.

I wanted to create clothes that were powerful, elaborate and able to toe the line between repurposed and wearable. I had no fashion design background, but I was precocious of mind, and understood the power of a cold email.

After reaching out to manufacturers from Honduras to China, however, it became apparent that I overestimated the power of said e-mail. Based on factory minimums that ranged from 100-1,000 pieces per design, I absolutely did not have the money to start a clothing brand.

I set up a bargain basement factory at my parents house in Port Jefferson: a vinyl printer, a rack of sweatshirts I had purchased for $4 a piece in black, white, and cream, a pair of fabric scissors, a heat press, and some iron on labels I had custom made on the internet. The idea was to cut up existing sweatshirts until they were just destroyed enough to be salvaged again, which is to say, so I wouldn’t have to start from scratch.

Starting with a white cotton crewneck, I cut slits in the sleeve cap, removed the hem, and added shoulder pads from my mother’s sprawling collection, which I had discovered in a Danish cookie tin where she famously kept all of her sewing supplies.

I was curious to see what would happen if I cut the elbows out completely, removed one sleeve but not the other, or let the hem trail asymmetrically. So I made another crewneck, in black this time. The more curious I became, the more sweatshirts I finished, and the better I got at whatever it was I was doing. When I overcut the sweatshirts, which I often did in this experimental phase, it became a tiny tank top or mini skirt to accompany an existing piece. I threw away nothing, mostly because I needed every scrap to tie the sweatshirts back together after cutting them up. At this point, I had very little idea how to sew, and the idea of a garment held together by nothing but itself seemed like a tidy metaphor for my entire life.

Surrounded by cut up sweatshirts, fabric scraps in every shape, mesh clippings, suede cords, elastic bands and spools of tulle that were wiry and impractical, I continued putting the pieces together until they resembled something wearable. I used the vinyl printer I had invested in to print quotes from my favorites books or parody corporate logos onto the rebuilt sweatshirts.

I did nothing but cut and tie for days at a time. Sometimes I went out to get sushi from the grocery market. In a rare moment of clarity, after weeks of putting off plans with friends or having a proper nights sleep, I thought to myself, maybe this project is too important to me, and I liked that.

Until this point, my career had always belonged to someone else. I was someone’s assistant, or someone’s agent, or I produced a photo shoot for someone. The past 6 years of being someone’s someone were necessary, but I couldn’t discount how good it felt to call something my own. Off Duty was so mine that for the first time in my life, the idea of another person’s opinion changing my mind about it seemed laughable.

I asked two models who I kept in touch with from the agency to be the first “Off Duty Girls” and both agreed to shoot the first campaign for free. There was no photographer, lighting or equipment, just three girls in a Chelsea photo studio I rented for $50/hour.

I cut and tied the models into the looks on the set and took their photos for the e-commerce website I would launch later that month.

The first collection sold mostly to friends, and otherwise badly. Financially, I still hadn’t broken even by the time I decided to make a second, but at this point the money meant little to me. It felt like my sanity was riding on my ability to keep creating.

Then in early 2021, after a year of delayed fabric deliveries, tailoring day and night, and giving away my homemade sweatshirts to models for free in exchange for promotional content, an Italian boutique carrying exclusively independent and emerging designers called 5way reached out via Instagram about selling Off Duty in their Milan shop. It had been almost a year since I had taken that train to Long Island on which everything went black.

I tried then to recall the fresh heartbreak of losing Nathan, the loneliness of quarantine that followed, the moments I was sure that I was in over my head, but none of this struck me as relevant. I remembered instead the joy of progress, the gratification of calling something my own, the interior world Off Duty had created for the girls who shared my vision.

Bemused and elated, I flew to Milan in May to see the second collection of Off Duty hanging in the windows of a boutique in the city’s center. I checked my phone to prove to myself that he was still gone. He was, still gone. But suddenly the loss was bearable. It had been the type of year during which it was difficult to be a creative. Everything changed, so I did too, and not unlike Frankenstein himself; an original thing was born from trivial debris.

About the Creator

Kalina Isoline

New York

writer/designer

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.