“You’re new here, huh?” he asked from his perch atop the red vinyl barstool at the end of the counter. An untouched chai latte was pushed off to the side in front of him--the milk foam slowly dissipating beneath the sprinkle of mahogany cinnamon spread over it--to make room for the small spiral bound notebook he used to sketch out rough abstract patterns. A wicked grin slinked across his lips as he eyed me from head to toe to take in my neon blue dyed hair, the bits of metal dotting my eyebrows and ears and lip, the ink on my arms: all the signals I’d acquired to separate myself from the mainstream, everything I’d donned to showcase my difference. “You’ll do.”

“You passed the first test,” Jeff, the owner of the cafe, smiled. “Now let me train you on the machine.”

I already knew how to use it—how to tamp the ground espresso with just the right amount of pressure, how to tell when the milk inside the pitcher was hot enough with just the right amount of microfoam to make the drink a latte or a cappuccino or a cortado—so the training went quickly. I’d been working in restaurants in my small town about an hour south of the city since the day I turned fifteen. But somehow, suddenly, in this basement coffee shop along Ponce de Leon, in the sprawling metropolis of Atlanta, with its magazine racks and brightly-colored wall murals and an actual labyrinth painted on the floor beneath the tables, everything felt new and magical. Like I had been reborn; like I was finally finding my place in the world. My legs trembled as a foal’s beneath me while I found my footing behind the counter. We were coming up on the turn of the century—1999 in Atlanta, Georgia—and everything around me was novel and fresh and brimming with possibilities.

“Make me another chai,” the man from the bar called. “Since you’re testing your skills.”

Jeff smiled and nodded before disappearing into his office or out to run some errand, leaving me alone to man the shop. Hands trembling, I placed the fresh mug and saucer beside the other untouched drink.

“Well?”

He scrunched his face as he inspected my work, but the gleam which seemed to alway emanate from his eyes gave him away from the stern demeanor he’d attempted. “Looks good.”

“Aren’t you going to try it?”

“Blood sugar’s high today,” he said, patting his hip in the same spot I knew my grandmother administered her own insulin shots for her diabetes. “I’m Tony.”

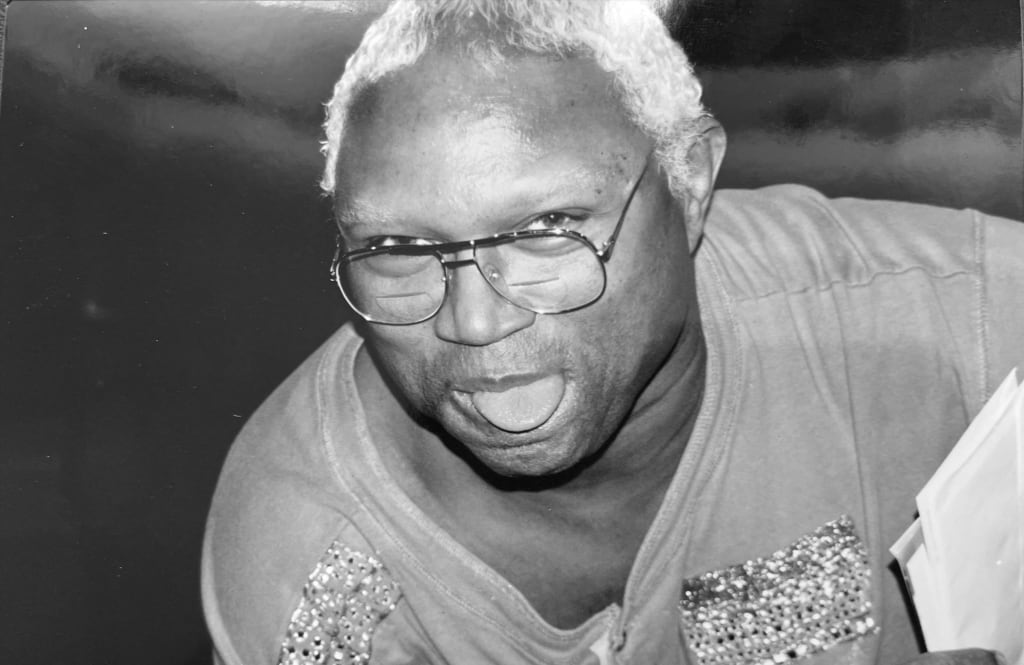

His hands were rough and large as they cupped my own. Long and yellowed slightly at the tips, his nails were thick but seemed to disappear entirely before they reached his cuticles. His bleached blond hair was cropped short and plastered with so much pomade the curls looked drawn onto his scalp. He had a round face and a grin nearly the size of a crescent moon, as bright and golden as the sun. Sometimes he wore glasses, but always he wore a dark gray Dollar Store sweatshirt over his broad shoulders which had been bedazzled with golden epaulettes of beads and glitter and rhinestones. His notebook was filled with designs he’d drawn to emblazon on other threads as soon as he returned to his apartment in the lofts above the shop.

I leaned back against the work counter and fidgeted with the rag tied to my belt loop.

“You’re a cute young thing,” Tony said. “How old are you?”

“Nineteen.”

“Baby.” He shook his head. “And how long have you been out?”

“A few years,” I shrugged. “Since I was fifteen.”

Tony nodded. He’d tell me later that he’d expected me to balk at the question, and that my casual acceptance of and response to it had given him a feeling of hope. That, in that moment, he’d, too, seen a glimpse of some greater future.

“I been out for longer than I care to admit,” he said. “But you just can’t hide this kind of glory.”

He shimmied his shoulders as he spoke, making sure each of the sparkles on his sweater caught the sunlight beaming in through the windows. It was hypnotic, the black and the gold of him shining there in the mid afternoon magic.

“Was it hard?” I asked. “Coming out back then?”

“For a black man in the South in the 1960s?” he mocked. “What do you think?”

“The Sixties?” I asked, feigning a shock we both knew was a lie. “What were you? A zygote? No way you’re a day over forty.”

Tony scoffed and smiled and pushed himself slowly to his feet. He capped his pen and tucked it into his notebook before shoving them both under his arm.

“I like you,” he said.

He walked slowly, breathing a little too heavily as he moved around the bar to mount the two flights of stairs up to street level. He laughed between huffs, and spoke more to himself than to me as he exited.

“See you tomorrow, I hope.”

Tony was always grinning, like his lips had forgotten how to do anything else; like if his smile remained, he could convince his body that everything was okay. He was “pushing 55” when he’d moved to Atlanta nearly a decade and a half ago, although he’d told me “a lady never reveals her true age.” He had a number of health issues, but the pills and shots and weekly dialysis appointments did their best to keep them in check. He’d tick them off like a list of things the world had thrown at him to rattle his spirit, but none of that ever made him falter. Most days he would saunter into the cafe with a flourish as he rounded the top step, arms wide to show off his newest sweatshirt creation of glitter and puff paint, and then settle in at the end of the bar to pour his dreams into his notebook and rarely touch the drink he insisted on ordering because he needed “to be a paying customer.” Other days he was more gregarious, sliding his notebook away and armed with stories of a past he was all too willing to share.

My own father was a good man, and he’d raised me well despite some tumultuous times in our history. It was from him I’d inherited my inquisitive nature, my want to take things apart to see how they worked, to understand them for the pieces which made up the whole. It was from him I’d inherited my stubbornness. Tony, though: He offered a history so many kids like me had needed; one we feared had been lost to crisis and erasure and ignorance, if in our naivety, we thought of it at all. He was one of the few elders who had survived, and, when he took me under his wing, it made me feel special and connected and somehow whole. He became a new sort of father, though he’d never let me say that. “Ain’t no one called me ‘daddy’ in thirty years,” he said. “And even then, it weren’t like that.” Still, he was the patriarch of the chosen family I was forming.

“They weren’t even really calling it that then,” he said. “The name was there. The doctors used it. But the newspapers, the ones who’d write about it, were still calling it The Gay Cancer. Like we were the only ones who could get it. Outed a whole hell of a lot of us who were living on the down low.”

He said it with a chuckle. Like he was flabbergasted. Like it had to be funny in order to keep moving forward. Like it wasn’t the medication—the ones he was grateful for when they finally arrived—that ransacked his kidneys and his liver and sent him to weekly rounds of dialysis.

“Were you scared?” I asked. I thought about the first words out of my parents’ mouths when I’d told them I was gay, all those years before this moment and so many years after Tony had received his own diagnosis: “What about AIDS? What happens if you get AIDS?”

“I was… not surprised.” His deep brown eyes glazed over as he thought back to that day in 1983. I imagined him there on the hard plastic examination table. I wondered if his smile faded at all when the doctor walked in examining the charts with the results of his bloodwork, her hands dipped in white vinyl and a double layer of cloth masks covering her mouth. “It seemed like everyone was getting it. So many of my friends. People just not showing up at the bars anymore. And then the others: the ones who got so thin and so frail and had those bruises and lesions on their backs and faces. Or the ones who never found out because they didn’t have the money or the courage to get the tests.”

I imagined him, young and lithe, dancing to the songs I’d grown up on from my dad’s cassette collection. In my mind, he had the same bleach blond helmet, the same shit-eating grin. The sparkle on his sweatshirt battled the light from the disco ball as he spun in circles on the dance floor while the figures beside him grew dark, grew faceless, and disappeared.

“We were scared, I think,” he said. “But we’d all been scared before. It was the rest of them who were more afraid. They didn’t want to touch us. Some of the doctors. Some of our own families. They thought burying us in the same ground would contaminate it, so they burned us down at the City Morgue and just left the ashes there.”

In high school, several of my classmates complained to the gym teacher about drinking from the same water fountain as me.

“We ain’t trying to catch no high five.”

It took me a while to realize they meant HIV, like substituting the virus for the Roman numeral made it—and me—somehow funny, more worthy of their jeers. By that time, we knew more about transmission—how you could and how you could not contract it—but the coach still asked if I would mind bringing in a water bottle from home. I refused, but I still stopped using the fountain.

I thought of all the unclaimed souls lining the shelves of the crematorium.

“Some of their families never knew.” His words haunted me. “Hell, some of us never knew. Our friends—our past lovers—our drunken one night stands. They’d be there dancing one night and then just not show up the next. We learned to not talk about it. We learned not to talk about a lot of things.”

I could tell, sitting there in the cafe, the sharp rich scent of coffee burning its way over the Nag Champa, that it was still difficult to speak of. But, beneath that, he was eager, and I was too. I think it was cathartic for the both of us.

“The thing you have to remember though:” he said, “that silence was a learned behavior. It’s what was abhorrent. I mean, there was always this level of secrecy in the queer community. We used coded language and handkerchiefs and metal rings stitched to our leather vests. We had code words and hand signals and spaces where we got to be authentic outside of the places we did not. But there was also a freedom to who we were, who we got to be. AIDS erased a lot of people, a lot of my friends, but it also erased a future when it erased our voice.”

“‘Silence equals Death,’” I said, quoting the ACT UP posters of the time.

“Exactly,” he smirked. “Don’t you ever forget that your voice is the most powerful weapon you’ve got. And you’ve got to use it every damn chance you get.”

Tony had lived an amazing life. He was there, in Selma, in 1965, marching across that bridge. He was in New York the night Judy Garland died, and he took to the streets. And though he’d sometimes mention a Marsha, he’d never confirm if he knew Miss Johnson, but in my mind he was by her side when she threw the first brick at Stonewall.

For me, growing up in the South, in the midst of and the wake of all of the fear and erasure in the news and our homes and our history books, it was hard to imagine the immediacy of the Civil Rights and Gay Rights movements. They seemed such a distant part of history, the way they were taught (or not taught), the way the young mind works. But here was this man, this beautiful soul, who had been there to witness it all. Tony had fought for my right to simply exist in a way that I could never fully understand, and he still had a smile on his face. His nimble old fingers still delicately places rhinestones on his sweaters to ensure he never had to hide, he would never be erased again.

Not all of Tony’s stories were about rebellion or struggle. But they were all about hope. He spoke of the joy—“even for those of us who didn’t like the song”—when a group of obviously queer men wearing the costumes of the culture rose to the top of the mainstream charts while singing about the dirty deeds done at the local rec center. He praised the tenacity of the queer women who had stepped in as surrogate mothers and nurses and families for the people who’d contracted the disease. His eyes were wistful and watery as he told me about his own addition to the Quilt, how sewing that patch together with thread and paint had been such a release, how it had pushed him into still creating his own garments to this day as a means of remembrance, of never hiding again.

Through the years I spent at that cafe, Tony became a father figure to me. He was ready and eager to pass down the stories of a history, of a generation which could have too easily been forgotten. He grounded me in place, in a past that was just as much my family tree as the one I’d been born into. And I was grateful. I was eager. I felt whole.

As time passed, Tony’s trips to the cafe became shorter; his trips to the dialysis clinic on the corner became more frequent. But his smile never faded. He’d sit at the end of the bar, always in the same seat—the one we’d long ago added a little metal placard to with his name—and order his chai latte, and push it to the side to focus on his notebook.

“You’ve gotten better,” he smiled as I placed his drink in front of him.

I knew that Tony, like his friends before him, would one day just stop coming. But in my memory he is always there, sitting atop the red vinyl stool at the end of the counter, sunlight glinting off the rhinestones and glitter on his sweatshirt, bouncing from his smile.

About the Creator

Andrew Forrest Baker

he | him

Southern gothic storyteller.

My new novel, The House That Wasn't There, is out now from April Gloaming Publishing.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.