History of the Opium Wars

Queen Victoria, through her victory during the Opium Wars, became the first drug dealing monarch.

In the 24th of May, 1839, perhaps in honor of Queen Victoria's birthday, the sun rose confidently over London and shone steadily throughout the day, uninterrupted by the clouds which plague even the best of English weather. But Lord Auckland, Governor General of Britain's colonies in India, received bad news from China as he was dining in the customary splendor of the occasion at Simla. In a determined attempt to finally end Britain's opium trafficking in China, the Chinese Imperial commissioner of Canton, Lin Tse-hsu, was holding the British trading community and the British Government’s Superintendent of Trade, Charles Elliot, hostage in their factories outside Canton. The ransom was to be 20,000 chests of opium. Thus began the Opium Wars.

By the time Auckland received this dispatch, Lin's demands had already been met and for the time being the traders were safe in Macao. From Macao, Lancelot Dent of Dent and Co. and James Matheson of Jardine Matheson, the two largest London opium houses, wrote to Whitehall—the 19th century British Empire's version of our State Department, combined with the CIA—to protest the Chinese action and to ask for intervention.

By 1840, Great Britain would be at war with China. For Britain's Foreign Minister, Lord Palmerston, and the British government, the only salvageable issue by which they could reason and wage this war would turn out to be the real one: “free trade.” The basis of this “free trade” which Britain demanded was opium.

By 1840 Europeans—especially the British—had been trying to establish a profitable trade with China for three centuries. The Portuguese first arrived in 1516. The first Dutch ship arrived at Canton in 1604, followed by the English in 1626. Although the Imperial Chinese government was not very enthusiastic about contact with foreigners, the traders persisted and, in 1685, the Emperor allowed commerce to be established at the southern Chinese port city of Canton.

Trade was to be conducted under a strict set of regulations and though the province’s Viceroy was ultimately responsible, it was beneath his dignity to meet face to face with any of the foreign community. The foreigners' intermediary was a Chinese mandarin the British called the Hoppo, who had purchased his post as Director of Customs at a very high price from Peking. The group of Chinese merchants the foreigners dealt with were called the Cohong—a syndicate granted monopoly over foreign trade but whose profits were regularly squeezed to help fill the coffers of the Imperial treasury.

In 1775 the East India Company, which had engineered the conquest of India for the British, set up its first factory at Canton. There was a problem with the China trade, however, which by 1800 became serious not only for the Select Committee of the East India Company in Canton but for the Governor General of India and indirectly Her Majesty's Government in London: The simple state of affairs was that there were no British goods the Chinese wanted. They had a self-sufficient economy and were not interested in the British manufactures, mostly woolens, which the East India Company was obliged to carry. On the other hand, the Chinese possessed a commodity which was much in demand and available nowhere else, namely tea.

By 1785 the British East India Company was buying and selling 15 million pounds weight of Chinese tea a year, and paying for the majority of it in silver. Then, as now, economics demanded that silver should be held onto, so the British felt a desperate need to find a commodity that could be sold to the Chinese, financing Britain's purchase of Chinese tea. The answer was to be found on the Ganges plain of Britain's India colony, and it was opium.

Patna and Benares Opium

Since 1772, when they conquered the territory of Bengal, the British in India had been using opium as a source of tax revenue, following a precedent set by the Indian Moghuls many years before. The opium named after the cities in the region it was grown, Patna and Benares, was packed into wooden chests, each containing about 150 pounds, and transported to the British opium factory in Calcutta.

At Calcutta's Tank Square, the opium was auctioned off three times a year to wholesale merchants for export. Soon Patna and Benares opium production became a British government monopoly and during the 19th Century it contributed one-seventh of the total government revenue for British India. Most of the exported opium would go to China, where its revenues would help to pay for tea and hopefully restore the balance of trade. (The tea trade itself was indispensable not only to the British merchants involved but also to the government in Whitehall. The tax levied on tea was to amount to one tenth of total government revenues in England.)

When the British governor of Bengal initiated a search for new Chinese opium markets in the late 1700s, he was aware that opium was a prohibited article in China. The first Chinese Imperial edict against its use and importation had been decreed in 1729. Although as late as the 1780s opium addiction in China had not reached alarming proportions, China's traditional Confucian morality could in no way be reconciled with the habitual use of opium.

By their will, organization, and naval power the British were able to raise opium sales to China from 1,000 to 5,000 chests per annum between the years 1801 to 1820. By 1820 an opium-silver-tea triangle between Britain, her Indian colonies, and China was firmly established, and opium became not only the tax base for British India but the pivot around which all China trade centered. By the 1830s, with the advent of private trading, such a flow of opium would reach China that the Chinese government could only react to the crisis in a way which would lead inevitably to war.

At the time the first Opium War began in 1839, Britain still did not have any official diplomatic relationship with China, even though English traders had been at Canton over a hundred years. China, after all, was the great, unchanging Celestial Empire. Vast, magnificent, and insular, for 3,000 years she had been the cultural center of the far east—and of the world as far as the Chinese were concerned.

When the Europeans had approached from the southwest in their great ships, China saw them only as a curious type of barbarian, different in outward appearance but in substance similar to the Mongol hordes that the Great Wall had been erected to keep out of the Celestial Empire.

“Our ways have no resemblance to yours,” the Manchu Emperor, Chi'en Lung, told the Irish peer Lord Macartney in 1793, when China rebuffed the first of Britain's diplomatic overtures. And, of course, on a scale of values there could have been no greater contrast. Britain was building a vast empire by trade and war; soldiers and merchants were among the lower classes of Chinese society. Britain was manufacturing goods cheaply by using steam power and everything in China was done by hand.

Britain had emerged from the Napoleonic wars as a world power with the most powerful weapon on earth, her royal navy; China did not have a navy and, as such, and could not think of herself as a world power. She was the world.

In 1820, when the Tao-Kuang Emperor ascended the Chinese throne, his Manchu dynasty was in a profound state of decline. Corruption and domestic uprisings had weakened the government politically and financially. The Mandarins, China's corps of scholar civil servants, were enriching themselves at public expense; soldiers and officials who were underpaid and discontented were beginning to turn to opium, weakening the government even further.

The Emperor, bent on reform, turned his attention to the problem of opium addiction, which was slowly but steadily spreading into the interior of China and was even being found among officials and eunuchs of the Imperial court. There had been edicts against opium at the rate of at least one a year since 1799 but they had had no effect. Under the auspices of the British East India Company, opium was arriving at a steady flow and many Chinese connived with the British opium houses, either because of their own addiction or the handsome bribes and profits they obtained from the trade.

His attention drawn to the problem by the Emperor, the Viceroy of Kwangtung and Kwangsi provinces made an unexpected move against the dealers in Canton, where a chest of Indian opium was selling for $2000. Native dealers were fined, imprisoned, or sent into exile. Tea trading was stopped for two months and four ships anchored at Whampoa were ordered to leave. One of the ships was the American Emily, and the three others were consigned to James Matheson, a senior partner in the largest British opium company on the China coast.

The Emily and one of Matheson's ships were holding opium. The traders were indignant at the sudden zeal shown by the Chinese, but they again devised a scheme which would end the present crisis and protect them from further harassment. They simply moved all of the opium receiving ships to an outer anchorage off Lintin Island, 20 miles south of the entrance to the Canton River. (European opium traders circumvented Chinese laws against dope smuggling by off-loading their oceangoing ships to Chinese receiving boats, which actually ran the illicit cargo to shore.) Armed with cannon, muskets and cutlasses, protected by boarding nets, these ships had little to fear either from pirates or the Chinese war junks. From now on the opium trade would be centered at Lintin Island. The Emperor undoubtedly received an exaggerated account of the Viceroy’s “victory” in ordering the opium traders from Canton, but it was a minor skirmish and the worst was yet to come.

The British East India Company increased its opium production in an effort to undercut competition and bring down prices. Eventually they were also able to control the transit routes of the competitors' opium and to tax it at Bombay, but the efforts to nullify the competition landed the company with huge stocks of opium and increasing production year after year. From a high of $2,000 a chest in 1822, Patna and Benares opium fell to approximately $600 a chest by 1832

In order to maintain the balance of trade in Britain's favor, an opium market many times larger than what it had been for the past 20 years had to be found. So that Brits could go on drinking tea and the industrial north of England could expand its markets, twice as many Chinese opium addicts would have to be created. Aided by enterprising agencies like Jardine Matheson and Co., the flow of opium to China increased from a steady flow to a flood.

In 1831 19,000 chests of Indian opium were sent to Canton. Not only did this keep the trade balanced, it turned it heavily in Britain's favor. Large quantities of silver were now beginning to leave China, and ships leaving Canton after the trading season were often loaded only with treasure.

Addiction began to spread rapidly among the common Chinese and the opium pipe, lamp, and stylus were sold openly in street bazaars. Not only were twice as many Chinese addicts create,d but twice as many British addicts too—the company generously supplying England with the opium she needed for “medicinal” purposes.

By the end of the 1820s the opium trade had increased on such a vast scale that a much faster way of transporting the drug had to be found. The old and sluggish ships, which could not stand up to the northeast monsoon, made only one trip a year. The opium traders wanted to make three runs a year, so they began to buy or build the fastest ships procurable. In December 1829, the Red Rover, named after the novel by James Fennimore Cooper and looking more like a privateer than a merchantman, left Calcutta for Canton. She was the first of the opium clippers and the subsequent success of her voyage meant that by 1834 a fleet of narrow, swift clippers would be plying the opium trade between India and China, defying the monsoon.

The opium clippers loaded their cargoes of opium at Calcutta's January sale and had them on the Chinese coast in February. They could be back in Calcutta for the May opium sale and then back again in July. At Lintin Island, business was booming. The clippers would transfer their cargo to the receiving ships, where it would be transferred again to Chinese craft built especially for the trade. These were 50-oared, two-masted galleys, heavily armed and called “fast crabs” or “scrambling dragons." These ships would emerge from the tiny creek villages surrounding Canton Bay, pick up the opium, and deliver it to their drop points where the buyer would be waiting. Things ran smoothly and the traders reaped huge profits.

Christ Vs Opium

Jardine Matheson and Co. had become the biggest opium house in Canton, but they did not let matters rest there. Instead they sent ships up the China coast looking for new markets. The clippers, with a broadside of four or five guns port and starboard and a heavy gun amidship, were more formidable than any naval force the Emperor might put against them. They sailed up the Kwangtung and Fukien coasts to Amoy and Foochow, where they would be able to sell opium, often accompanied by Protestant missionaries who acted as interpreters for the captain and crew. The missionaries, obsessed with the printed word of God, would dispense versions of the Bible awkwardly translated into Chinese from one side of the ship while opium was sold from the other side. Christ, however, did not prove to be as irresistible as opium.

From 1836 until the outbreak of hostilities in 1839, the Chinese Imperial government waged its most determined campaign to suppress the opium traffic at Canton, although the odds seemed to be inexorably against success. Corruption was rampant among the mandarins, half of the army was addicted to opium, and the court was financially bled white by the flow of silver from China and the high cost of suppressing domestic rebellions. The Manchu dynasty, themselves foreigners from Tartary, were constantly aware of the precariousness of their rule and always sought to place the safety of the dynasty ahead of everything. There were suggestions that perhaps opium should be legalized, imported as medicine, and taxed. There were various memorials to the Emperor which included plans for the rehabilitation of addicts as well as ideas on how to stop its use and traffic. Although there were in fact more favoring legislation, the Emperor, adhering to Confucian tradition, decided that the plague must end.

Opium Executions

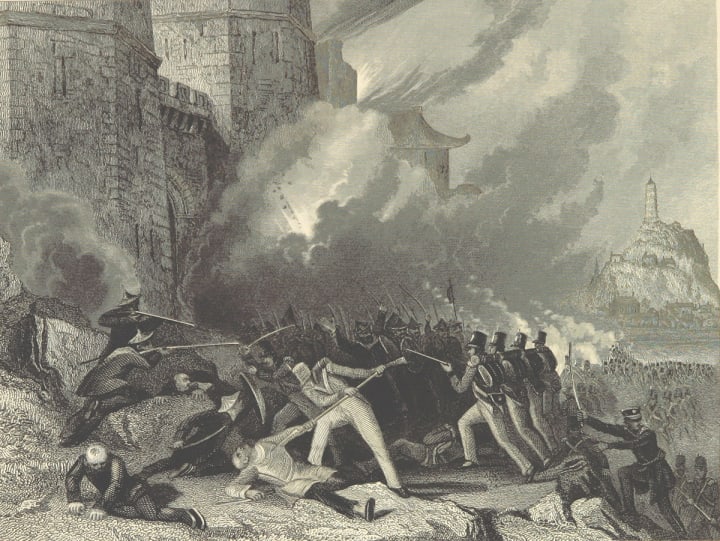

In Canton, opium dens were closed, merchants harassed, fined, and imprisoned; Cohong warehouses were raided if they were believed to be harboring opium, goods confiscated, even the fleet of “fast crabs” and “scrambling dragons” were destroyed by the war junks which comprised the Chinese Imperial Navy. There were riots when soldiers tried to confiscate villagers' opium; there were riots outside of the factories when soldiers attempted to stage executions of known Chinese opium dealers for the foreigners' benefit. The British opium traders found that by the autumn of 1838 it was exceedingly difficult to get their wares on shore.

Then, in March 1839, the new Chinese High Commissioner for Canton, Lin Tse-hsu, arrived. Lin was especially appointed by the Emperor to find a way of ending the opium traffic for good. Lin immediately called in the 12 senior Cohong merchants—the Chinese traders who middled the opium from the British. He read an edict stating that the foreigners must give up all of their opium and bring no more to China. If they did not comply, the Chinese middleman merchants would be executed. In the meantime, all trade was to be stopped and the foreign community placed under house arrest.

Charles Elliot and James Matheson viewed the situation gravely. The Cohong merchants were genuinely terrified, and although Elliot had written to both Palmerston and Auckland requesting naval support it would be months before that could arrive. They had three days to comply with Lin's request and the situation seemed impossible. But Elliot made a decision—he asked that all opium first be turned over to him as the representative of Her Majesty's Government. Whitehall, he said, would pay for the confiscated opium and he acted as if he were actually empowered to make such an offer. Elliot knew, however, that Palmerston could never get Parliament to accept such a proposition, and that after the opium was turned over the reimbursement Elliot had promised in the British government's name could only be obtained by the Chinese through war.

On Macao—an island near the British colony of Hong Kong—the atmosphere was tense and no one was surprised when at the end of August, Lin ordered the Chinese Governor General of Macao to expel the British. On the day they were to leave, the 26-gun British Royal Navy frigate Volage sailed into Canton Bay and escorted the merchant fleet to Hong Kong. At Hong Kong they were joined by the 18-gun British ship, Hyacinth.

First Opium War

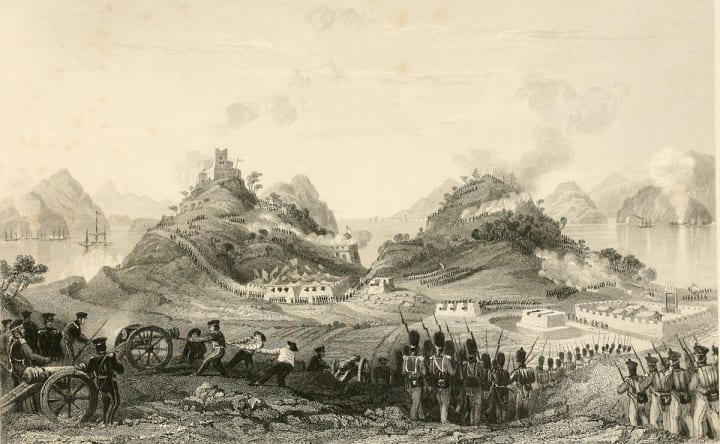

That October, as the tea season approached, Lin and Elliot were forced toward a rapprochement over trade. Both the British and Cantonese tea merchants pressed for a resumption of legitimate trade. The entire British trading community had remained adamant in their refusal to sign the anti-opium bond and Lin finally decided to let them trade without doing so—provided the ships were first searched for opium. At the end of October the merchant fleet moved to a spot outside Canton harbor, waiting for such an agreement to be finalized. Then an old merchant ship, the Thomas Coutts, entered the harbor and agreed to the anti-opium bond. British solidarity was shattered and Lin, furious, demanded that all British ships do the same or he would drive them from the coast. As Lin marshalled his forces, Elliot sent the Volage and Hyacinth sailing toward Canton. On the second of November, the British warships reached Chuenpi, where they found the Chinese Admiral Kuan with 16 war junks and 12 fireboats. On the following day, the two British ships moved up and then down the Chinese line, delivering broadsides as they went. The contest was terribly unequal. Four junks were sunk, the fireboats scattered, and the terrified Chinese crews deserted most of the remaining ships. The first Opium War had begun.

In 1839, British opium merchant William Jardine had returned to England to wage a determined campaign for war with China. In September a meeting with Lord Palmerston was arranged for him. (Palmerston had recently received the news of the 20,000 chests of opium confiscated and of the indemnity that Jardine's colleague, Charles Elliot, had promised Whitehall would pay—which turned out to be over 2 million pounds. As Elliot had prefigured, Parliament would never agree to the reimbursement.) Jardine had brought with him his maps and charts of the China coast. The navigational secrets he had accumulated during his years in the opium trade would be invaluable to the British Admiralty in the event of war. Palmerston studied the charts with Jardine and the two men discussed the exact naval force that would be required. In November 1839, an expeditionary force composed of 16 men-of-war, four armed steamers, and 27 transports carrying 4000 troops sailed for China.

On April 7, 1840, Parliament debated the China question. The opposition leader, Sir Robert Peel (later organizer of the first public police force in modern history: London’s “Peelers,” who went on to become today’s “Bobbies”), introduced a motion of censor against Palmerston's actions and the threatened war with China. In reply, Thomas Babington Macauley, the Secretary of State for War, gave an oratory reminiscent of one of his famous historical essays, praising British valor and a Britain unaccustomed to defeat.

Peel's motion of censure lost by nine votes and Britain was at war with China. In Edinburgh at this time, Thomas De Quincey, sick and alone, was making futile attempts to reduce his consumption of opiated laudanum, which was now up to 8,000 drops a day. In June 1840, the British Expeditionary Force arrived in Canton Bay. The British blockaded Canton harbor and the opium trade was reestablished at Lintin Island, the drug now being openly run ashore in daylight. Leaving four ships to continue the blockade, the rest of the British fleet sailed north to establish a base near the mouth of the Yangtze River from which they could threaten the flow of supplies to the Imperial Chinese capital at Peking.

Pattern of War Established

Chou-shan Island and its harbor city of Tin-hai were the target. Only nine minutes of broadsides from the British warships demolished the walled town. Chinese civilians ran screaming as the Madras artillery quickly landed four of its guns and began pounding the city's defenseless remnants. By nightfall, drunken British soldiers had plundered Tin-hai until there was nothing left to take. The pattern of the war had been established. Against the British forces the Chinese had no chance whatsoever.

Against the most effective war machine in the world, with its formidable array of modern weaponry, the Chinese could only range the most antiquated cannon; and their fleet of cumbersome, gaudily painted war junks with fixed guns were open prey for even the smallest of British frigates.

The bulk of both armies was made up of criminals and misfits, but while the British were regularly flogged to ensure their strict submission, the Chinese corps was riddled with opium addicts, officers in the mist of battle often ignoring orders because they were smoking their pipes. The British were well armed and fought in the infantry patterns of the Napoleonic wars. The Chinese were using old matchlock rifles and spears, and their traditional tactic was to make a lot of noise in order to frighten the enemy away.

In this campaign, at least, the British soldiers lusted for battle. The Chinese often ran away. The Chinese commanders, however, obliged by their filial duty to the Emperor, fought valiantly against these insurmountable odds and when they were defeated they committed suicide. The Emperor's elite Tartar troops also fought well, but at Shanghai they were slaughtered by superior British weaponry and their wives all killed themselves rather than be raped by the barbarians.

There were only a few major battles fought in this war—Chinese strategy, in part, was to open prolonged negotiations with the advancing British army in order to “wear them down.” Shanghai fell in 1842 and so did the fortified town of Chinkiang, which protected the approach to Nanking. On the ninth of August 1842, Nanking surrendered and the British plenipotentiary, Sir Henry Pottinger, extorted from the Chinese the enormous indemnity of $21,000,000 in the Treaty of Nanking, which concluded the fighting. The Chinese also had to negotiate with the British as equals, according to the treaty, and the rich cities of Amoy, Foochow, Ningpo, and Shanghai were opened to European trade. The only concession that Pottinger did not get, one which Palmerston had specified, was the legalization of the opium trade. On that item the Chinese would not budge.

Second Opium War

The next 15 years were disastrous ones for China. She was plagued by piracy, rebellion, the expansion of European colonialist exploitation, and, of course, opium. Claiming China was not honoring the Treaty of Nanking, the British, allied with the French, initiated the second Opium War campaign in 1856. In 1860, the allied forces led by Britain's Lord Elgin sailed up the Pehho River to the Emperor's Summer Place outside of Peking. At the exquisite Summer Palace, laid out in 80 acres of parkland, were stored the treasures of the Kingdom: ceremonial robes and jewels, baled silk, the processional treasures of the Imperial Court, as well as libraries and collections of paintings. The Summer Palace was looted and burned. Afterwards the Chinese capitulated to all the foreigners’ demands.

The Chinese Celestial Empire, which had existed longer than any in recorded history, was thus “opened” to Europe’s “free trade.” Opium was at long last legalized—but to the dismay of the traffickers, China now decided to grow her own.

About the Creator

Aunt Mary

Lives in Englewood, NJ, and can often be found sharing her weed wisdom at Starbucks.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.