History of LSD

The history of LSD begins with its legendary forefathers.

“I feel like I’m part of a gathering of the most exquisite rascals of the age!” Ram Dass exclaimed at a colloquium in 1977 at the University of Santa Cruz entitled “LSD—A Generation Later,” featuring the man who discovered the king of the psychedelics himself, Dr. Albert Hofmann. With dozens of acid aficionados attending, it was the first time to get public record of the thoughts and feelings these masterminds had on what could be considered a miracle drug.

It was “the largest collection of burn-outs ever assembled on the planet,” according to Ken Kesey, who regretted he could not attend the mythic reunion of those whose public exploration of their egos has changed our private lives. The two-day seminar was sponsored by the UCSC Psychology Board, two book publishers, and the Network, a student organization with community centers in Santa Cruz and Berkeley, California.

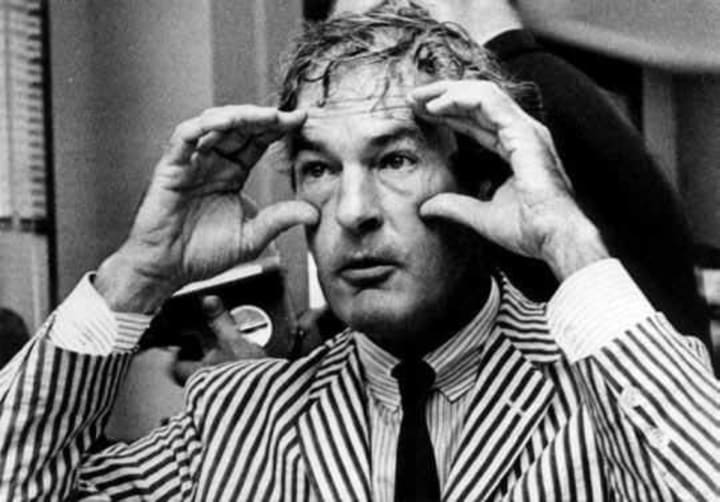

And there, mingling beneath the redwood pines of Kresge College (AKA Touchy-feely-ville) were such luminaries as Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg, Ram Dass (Richard Alpert), and Ralph Metzner, meeting for the first time in many years. And the energy was high, to say the least, as they were surrounded by an appreciative crowd of students, press, and other notables, watching the men exchange newspaper clippings and photos of the wife and kids. For some, it was an evolutionary event.

Patriarchs of the Psychedelic Age

Image via NYPL

“You’ve been hitting all the high spots,” Ram Dass, dressed in a light summer suit, told Leary at Friday afternoon’s reception. "But, the punch was not electric."

“I’m here now!” Leary laughed at his pun on Alpert’s book. With his ascot and pink shirt, Leary definitely had the air of a movie star but his acid-eating grin gave it all away. “LSD just makes us aware we’re all assholes!”

“Tell me you’ve got a new idea,” smiled Ralph Metzner, who had been one of Alpert and Leary's students at Harvard and had edited The Psychedelic Review, along with teaching at the School of Actualism in San Francisco.

“Nothing’s new,” Leary cracked. “No more new ideas!”

“Every time I move I think of you,” Ram Dass said to Leary. “You’ve trained me to save my memorabilia—I may be history someday—I’m afraid to throw any of this shit away.” The last time the three of them had all been together was at Leary’s LSD commune in Millbrook, New York, where G. Gordon Liddy was the local DA. Then came the legendary parting of their ways. Metzner moved onward and Alpert changed his name to Ram Dass, while the government “did a Gulag trip” on Leary, Allen Ginsberg told Hofmann, to discredit Leary in the eyes of young people who had first heeded his “Turn on—tune in—drop out'' dictum.

“It got very political after the war,'' Ginsberg said to Hofmann, “with the CIA using Leary as a scapegoat for what they themselves did with LSD.” The doctor nodded as he shook hands with Leary.

“You wrote me a wonderful letter when I was in prison and I thank you for that,” Leary said.

“It all started with chemistry . . .” Hoffman replied.

“God started with chemistry,” Leary laughed.

“Doctor Hofmann,” said Stephen Gaskin, “there are probably several thousand people living on The Farm who think they owe their life to you!”

Regarding his discovery in 1943 of LSD’s hallucinogenic properties, Hofmann said, “I did not know at the time it would have such an impact—in science I knew—but not in social terms.”

“It was a premature discovery,” said Dr. Stanley Krippner, former director of the Maimonides Dream Lab in New York and author of The Realms of Healing. “LSD came along before our culture was ready for it. I think we’re still not ready for it. We haven’t used it for its greatest potential. Psychedelic substances have been used very wisely in primitive cultures . . . for spiritual, healing purposes. Our culture does not have this framework. We don’t have the closeness to god, the closeness to nature, the shamanistic outlook—we've lost all that.”

The Counter-Culture Chemist

Image via ABC

How best to achieve that outlook? That was a question that many people at the conference have searched their minds to answer.

“You may be disappointed,” Hofmann addressed the excited audience at Friday night’s colloquium. Outside the dining hall was like a rock concert, with a thousand people waiting for some miracle to happen, their faces pressed against the glass. “You may have expected to meet a guru and you meet just a chemist!” Hofmann proceeded to give a chemistry class to the counter-culture, complete with slides of the molecular structure of lysergic acid diethylamide. When the 73 year old scientist toyed with the flashlight pointer, the crowd whooped. When he sipped a glass of water and said “is not LSD,” they roared. Clearly these folks had definitely been there.

Hofmann basically presented the same talk he had given earlier in that week at a seminar on pharmacology at the University of California’s San Francisco Medical Center. “It’s an old story,” Hofmann said of his discovery of LSD at Sandoz Pharmaceuticals in Basel, Switzerland. While experimenting with ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and when baked into bread causes “St. Anthony’s Fire,” or ergotamine poisoning, Hofmann manufactured the chemical compound that was later to be known as LSD-25 in 1938.

The story goes that he did not learn of its psychedelic properties until 1943, about the time Enrico Fermi initiated the first atomic chain reaction in Chicago. Metzner claims there’s an evolutionary link. Regardless, Hofmann somehow became so intoxicated that “the external world became changed as in a dream . . .” And thus it was that the Western World took its first real acid trip.

To say this new drug was more powerful than mescaline, synthesized from the peyote cactus in 1919, is an understatement as anyone knows who has made the fateful comparison. Hofmann went on to explore two “magic drugs” of Central America.

“In a sense LSD brought the Sacred Mushrooms into my laboratory,” Hofmann explained. Gordon Wasson's researchers aware of his work at Sandoz had sent him some samples of Teonanactl from their expedition.

“To see if they were still potent, I decided to test them on myself,” Hofmann began. “At 8:32—” The audience cheered. “Everything assumed a Mexican character . . .” From these mushrooms he had synthesized psilocybin and psilocin.

In 1962 Hofmann joined an expedition to Oaxaca where he visited the curandera Maria Sabina, and gave her psilocybin to use in her nocturnal mushroom ceremony. “I explained to her that the spirit of the mushroom is in these pills.” Later she told him there was no difference between them. “This is final proof,** Hofmann said. His synthesis was correct.

Hofmann also found ergot alkaloids in morning glory seeds somewhat similar to those he had isolated in the earlier experiments. His slides showed how closely LSD and psilocybin chemically resemble serotonin, a neurotransmitter that carries nerve impulses across the synapse from one nerve cell to another. This, then, is the interface between magic and science. The secrets of the mind are within the grasp of human technology. To what use this knowledge is applied depends on the social conditions of our society.

“Nobody has died until now from LSD—not one casualty case,” said Hofmann in a response to a question. “But many things happened, of course, after taking LSD, jumping out the window and other accidents. But the lethal dose, the toxic dose of LSD is not known. From a physiological point of view, it is not dangerous but it may be very dangerous—it could have a very bad effect if you are not prepared for this experience as is the case when the CIA or the Army gave it to people who did not know they did get LSD.”

“First of all,” said Krippner, “the military got a hold of it and now we find out that the worst rumors are true—innocent people were given the drug.”

Recent revelations in the establishment press concerning the Army and the CIA’s LSD experiments in their MK-Ultra program were briefly covered in a Saturday morning workshop conducted by Marty Lee of the Assassination Information Bureau in Washington, DC. He claimed to have read over 12,000 pages of documents released by the CIA under the Freedom of Information Act pertaining to the CIA’s behavior control projects. LSD experiments were only part of the strategy to win “the battles for the minds of men.” There were 149 sub projects according to a 1963 CIA memorandum “concerned with the research and development of chemical, biological and radiological methods capable of employment in clandestine operations to control human behavior.” Research was also carried on above ground through conduit organizations like the Society for the Investigation of Human Psychology.

“It seems to me that some place along the line everyone in the psychedelic movement was rubbing shoulders with somebody who was at least rubbing shoulders with, very closely with, the Agency or the Army and so forth,” Lee stated. “There were connections. For the most part it was unwitting, but not completely.”

“My first acid trip—regular acid,” said Allen Ginsberg, “I did at the Stanford Institute of Mental Health in 1959. Kesey did acid there for the first time, too. Those were experiments funded by the Army! We should look into the rise of the LSD fad,” Ginsberg continued. “Maybe they turned us on and sent us out to work on the counter-culture . . . To some extent I was an agent of the CIA!”

“I had a friend in San Francisco who I suspected was living in that kind of a house (a CIA safe house used in the MK-Ultra program),” Gaskin asserted. “They’d bring in a square cat they’d picked up downtown, dose him and dance around him and chant—try to put trips into his head like ‘you ought to grow your hair, you ought to be a hippie.' I guess if the CIA was going to try something out that would be a pretty reliable thing to do—catch a banker and see if you can make a hippie out of him overnight!”

Regarding unwitting subjects of drug experiments, Lee said, “We’re just at that time where people will start coming forward because they didn’t know before what had happened to them.” Lee requested that people who think they may have been victimized contact him through the Assassination Information Bureau at 1322 18th St. NW, Washington, DC 20036.

Doctor's Orders

Image via BBC

Most of the guests that attended the “reunion” were so glad to be out of jail they didn’t want to discuss the implications of MK-Ultra nor the government’s attitude toward drug offenders. But the reality was there, nonetheless. Although the laws remain, their enforcement is lax and “the movement” certainly has lapsed.

Sitting on Saturday afternoon’s panel, Dr. David Smith of the Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic scanned his “notorious” company and said, “Some of the people here were vilified by society as evil-doers at the same time the Army was giving acid to unsuspecting people and they were having horrible trips. And they were considered patriotic.”

“As I look at my colleagues and myself,” said Ram Dass, “I see we have proceeded just as we wished to—despite all conditions . . . And I feel what we are doing today is partly demonstrating that we are not psychotic! I’m not sticking around waiting for LSD to be legal. It’s quietly becoming somewhat of an irrelevant issue and as it does, the whole thing opens up very slowly.” Ram Dass said he hoped to see a more favorable climate for LSD research into its potential for human development.

“I’d like to free the whole thing and get it back to where it was prior to 1963,” said Dr. John Beresford, who had helped set up an open-ended LSD research foundation, the Agora Scientific Trust in New York City.

“Our medical model,” said Krippner, “is a pathological one based on a negative approach. Patients were sometimes strapped to a table and electrodes stuck to their heads. How many new people apply for grants will be the test of the times.”

“I asked Dr. Hofmann what was his final philosophical conclusion about LSD—what does it all mean to him?” Ginsberg told the panel audience Saturday after Hofmann and Leary had left the day before. “He said his last trip was 1970, in Germany. Why didn’t he continue? Well, he said, he had taken it there twelve times. He had learned the experience. He had had the experience and there was no need to go back and re-experience that same experience in a similar mode. It was that LSD in a sense was self-limiting. He said there are many worlds, many universes, many realities. Well, I said, don’t you take LSD to explore these different realities? No, he replied. “I just go into the woods in the morning and explore them by myself—without LSD.’”

Enlightenment or Acid Trip?

Image via Clocktower

Before coming to the conference Ginsberg had done his psychedelic homework, dropping acid before taking the plane. “The conclusion that I came to was that the insight that I was getting from traditional and classic Buddhist meditation was similar to the insight that I finally arrived at under the acid. Or, perhaps, that the Buddhist meditation had so influenced my tripping that both the acid and the Buddhist mode of mind were identical. And the lesson was that form is emptiness . . . There's no need to get hysterically hung up on any thought form. I mean if you grab–no wisdom, no enlightenment, no illumination, no god, no identity, no self, no reference point—that any grabbing for a reference point is vain. And that’s one of the first things you think when you get high, that even if you didn’t get high you’d be seeing the same reality . . . And that, in a sense, acid is not necessary and that’s why it's okay!” Applause.

“If anything," said Ram Dass, “I met Tim last night, and I met Ralph, and I meet Allen again and again, and I met John Beresford-all such people that come up out of the past for me—I am delighted to see that we meet in a lighter, clearer space. Less clinging, less heaviness, less busy being somebody who we think we are. It’s as if it’s more a gathering of nobody special. We realize we are a statement of all we’ve been doing with our consciousness all these years. It’s not so much the words we’re saying; it’s what we are. We didn’t curl up and disappear because we were the bad guys of society. We’re right here; we feel love; and we feel compassion.”

“Abandon all the words you’ve heard today,” Dr. John Lilly, author of Center of the Cyclone and a famed dolphin researcher, admonished the audience. “Don’t get stuck by traditions, even the psychedelic tradition which has developed in the last generation. Don’t try to reproduce my experience. Abandon your forebears in this field because the future is for the innocent—it’s not for us. We are finished; we are published!”

At the big party Saturday night, with Ginsberg chanting Sita Ram at the crescent moon, with the various groupies and hangers-on making the scene, reciting whole earth poetry or just plain digging themselves, I ran into a rather inebriated photographer who was triumphant that she had just told Ram Dass “he was full of shit! I just kept telling him he was full of shit and finally he got tired of arguing with me and just walked away!”

I looked over and saw Ram Rass with Stephen Gaskin, both sitting cross-legged, rapping intently with their faces just inches apart. This party was full of contradictions, I decided. Nobody offered me any acid—but I wasn’t looking for any, either. I was just looking.

So this is what became of the Love Generation within ten years of its late 1960's pop-culturalization. LSD fell out of favor over the next few decades until it eventually became fodder for a look back on the beginnings of the modern day enlightenment of humankind. Recently, a rebirth has occurred. With the rising popularity of music festivals and counter-culture comes the rebirth of acid experimentation. What The Grateful Dead was years ago, Umphrey's McGee is today, gathering together people of like-mind wanting to expand their minds. Possibly due to the current state of our political makeup in this country, the hippies are back with a vengeance...or ya know...some acid, or whatever.

The history of LSD is as colorful as its participants. The spread of LSD had a profound impact on not only its users, but also society as a whole. People wanted a revolution and this powerful drug gave it to them. This engaging novel by Martin A. Lee and Bruce Shlain exposes the role the mind-altering drug played in history and how it will continue to influence us moving forward.

About the Creator

Frank White

New Yorker in his forties. His counsel is sought by many, offered to few. Traveled the world in search of answers, but found more questions.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.