America’s First Legal Pot Smoker

This is the story of the first legal pot smoker in America, Robert Randall.

The true story of America’s first legal marijuana smoker was chronicled in 1979 by Michael J. Weiss. For the first time in digital format, here is his report on the first sit down with the Legend, Robert Randall, the first man to legally smoke pot in this country.

The Apartment

A marijuana haze hangs in the stairwell leading to apartment 709-A. It wafts into rooms filled with antique signs and dingy books that seem to have aged from the omnipresent mist. Whispering in the background, a classic guitar piece completes the effect: a contemporary Washington D.C. walk-up turned into a Victorian opium den.

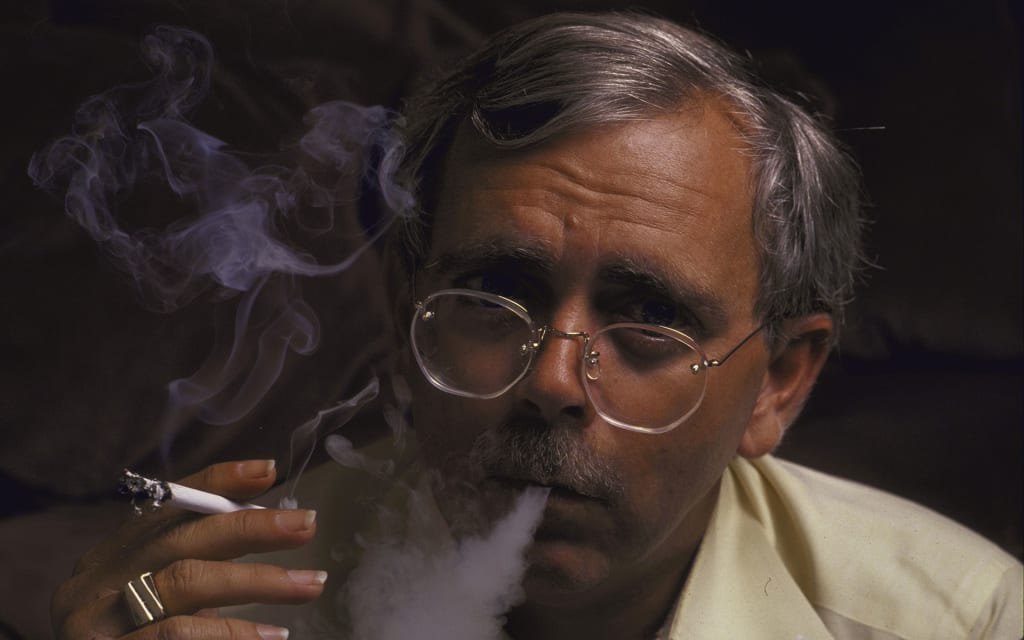

It’s mid-afternoon and Robert Randall is already on his seventh joint of the day. He takes a leisurely drag on it, a fat and evenly-rolled number held from a tiny roach stone with a marijuana leaf painted on top. By his arms sits a wooden box that Bogaert might have owned to stock the lights for all the leading ladies in Hollywood. Randall takes off the top reveal 60 joints, identical to the one he’s smoking: seedless, stemless, machine-rolled and government-issued. The pear green grass has twice the potency of most street pot and the quality is forever constant. This batch alone would make any drug dealer envious.

Robert Randall has glaucoma, an incurable eye disease that afflicts 4 million Americans. The disease has already damaged the optic nerves of both his eyes and left him partially blind. But Randall has hope, as long as he has access to marijuana, pot being the one antidote that can stabilize his condition. He’s gone to court twice to win the right to save his sight with grass. And he’s won both times to emerge as the nation’s only legal herb smoker with private domain over federal marijuana stocks. Put another way, Bob Randall’s reliable drug dealer is Uncle Sam.

“Oh, I’m not complaining,” says Randall between drags on the government homegrown. “Ultimately, I’ve gotten better treatment than anyone in the United States.”

Every day, seven days a week. Randall smokes 10 marijuana cigarettes to ease the pressure on his eyes. He supports himself by speaking appearances and is currently working on a book about his experiences with medicinal marijuana. He travels around the country, smoking grass in public and advocating its legal use by sufferers of glaucoma, cancer, multiple sclerosis and asthma.

Image via Growery

The Source

Randall's pot is grown on a five-acre federal farm near the University of Mississippi, rolled into cigarettes in North Carolina, and dispensed in brown-tinted plastic prescription bottles by NIDA. He describes the taste as “very metallic and flat” when compared to street grass. ("People at NIDA call it 'Bethesda gold.' It should be 'Bethesda green.' ")

Now thirty-one, Randall first discovered he had glaucoma in 1972. A native Floridian who received his BA and MA in Speech at the University of South Florida, he started smoking pot while in college. For years he had complained of eye problems and was seeing hazy rings around lights, but an optometrist diagnosed the condition as eye strain. Curiously, Randall recalls that those halos seemed to disappear when he was stoned on marijuana, though he never made any medical connections.

When he was diagnosed for glaucoma, Randall was twenty-four and driving a taxicab part-time. He was told that he had only three to five years of sight left and was placed on conventional medication. Aware that he was steadily losing his vision, he moved to Washington to take a speech teaching job at a community college. It was there that he accidentally discovered marijuana's benefits in treating glaucoma.

One night after smoking a couple of joints, he noticed his glaucoma symptoms vanishing with the smoke. And in his words, “I suddenly underwent a revelation, a very holistic comprehension not only of what was occurring but of its implications.”

For four months, Randall began a pattern of self-medication. He didn't tell his doctor for fear of the criminal implications of his treatment. But the story went public in mid-1975 when Randall was busted for growing his own pot.

Legal Decision

In November 1976, the government finally dismissed its charges against Randall. In a landmark decision, Randall became only the 13th defendant since the signing of the Magna Carta to win a common-law judgment on the grounds that he had broken the law out of medical necessity. He can still quote verbatim lines from the judge's 20-page decision: “It’s doubtful that speculative, suspect, and undemonstrable harm (from smoking grass) are more important than the defendant's right to sight.” The victory gave Randall legal access to government marijuana and permission to possess marijuana anywhere in the country. After getting ignored by three federal agencies charged with regulating drugs, he was finally placed in an experimental program to receive grass from a Howard University doctor.

Randall may have lived happily ever after on that program. But in January, 1978 his physician moved out of town and the government used that as an excuse to deny him further grass. He was bounced from one bureau to the next. No other doctor was willing to put up with the criminal risks that might implicate even MDs handling marijuana. Fearing for his sight, Randall decided to return to court.

“Bob was most reasonable about his situation, but I think he was very desperate,” remembers Tom Collier, the attorney who handled Randall's second case. “He had attempted everything that he knew how to do to resolve the situation himself and he had come to an end. He was looking for legal counsel to investigate other alternatives and filing suit seemed to be the answer.”

Round two of Randall's day in court lasted five months, during which time his eyesight continued to deteriorate.

The Food and Drug Administration gave him an experimental drug that didn't work—they'd resort to anything but grass—and Randall scoured the city to secure “extra-legal” pot. Aside from his focus on finding marijuana, he began to develop literal tunnel vision while awaiting the outcome of the trial. When he finally won the case and the government was ordered to provide him with 10 joints a day, Randall was tired and bitter.

Says Randall: “Rather than admit that marijuana might have a medical use and pursue that kind of information aggressively, the federal response has been to discourage people from trying to get access to a drug that might help their condition. When I won my second case, it was like receiving a payoff: 'Take the dope, shut up and enjoy yourself. Don't tell anyone else.' I was to forget that other people had medical problems.”

Of course, Randall did nothing of the sort. And the media was scarcely willing to ignore the only American who had a claim to the entire marijuana supply in the US. He became a national celebrity for the pot subculture as much as for the thousands of seriously ill patients hoping to alleviate suffering with marijuana. Randall's eyes were proof that pot wasn't solely the medical hazard that narcs had been attacking for years.

Photo via Toke Signals

From Ground Breaker to Recluse

Nowadays, Randall lives quietly in a Capitol Hill apartment with three cats, an overabundance of hanging plants and a study brimming with clippings and correspondence about the medical uses of marijuana. He says he supports legalization for recreational use, but his prime concern is the drug's therapeutic benefits. Since his first court case he's received a steady flow of letters from glaucoma patients seeking information about his marijuana treatment. He's corresponded with prisoners busted on pot while trying to find relief from their own diseases.

“He’s provided the medical issue with a human dimension,” states Alice O'Leary, a longtime friend and the director of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws' Medical Reclassification Project. “I think he's given a very large number of people the courage to come out and say, ‘Marijuana helps me and I need access to it.’ At one point, Bob said: ‘It’s not a very good feeling being the only one in the lifeboat.' And I think that sums up how he's felt for a long time.”

His own vision today is better than it was when the glaucoma was diagnosed in 1972, says Randall. Although 90 per cent of the optic nerve in both eyes is dead, his thick-lensed glasses correct one eye to 20-100 vision, the other to 2020. He has a diminishing peripheral sight that will ultimately lead to extreme tunnel vision. And though the prospect of going blind remains very real, it's an eventuality he's learned to deal with after five years.

Anger Management

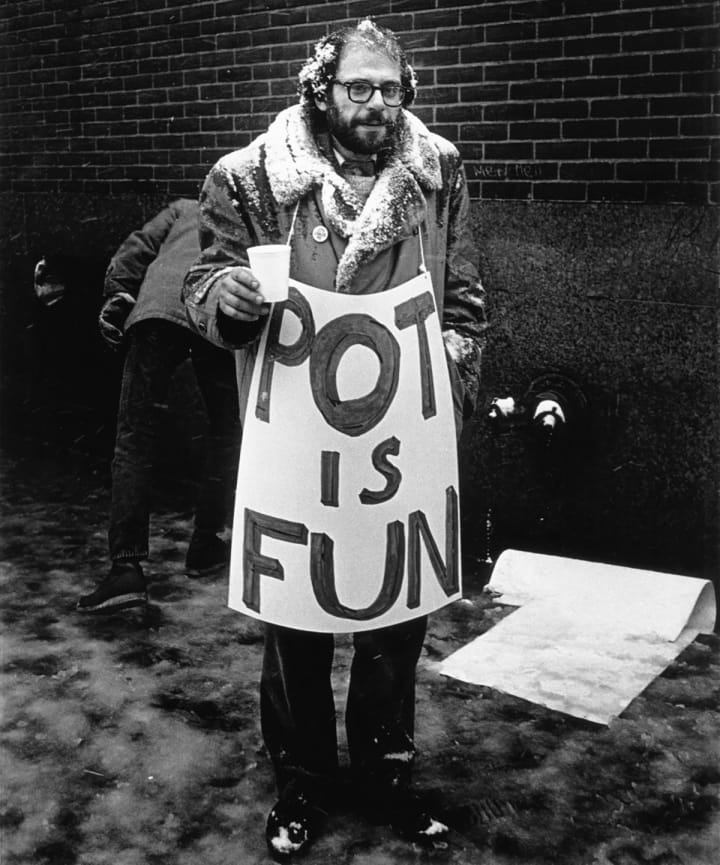

Politically, however, his feeling of bitterness lately has changed to a sense of outrage.

“It’s the tyranny of the bureaucracy,” says Randall, staring blankly at the smoke in his apartment. “Here is a weed that is significantly helpful in the treatment of any number of medical conditions. And yet the bureaucrats continue to say, ‘It’s evil, it's addictive, it'll cause insanity.” Suddenly for irrational reasons, politicians assume they have scientific knowledge. That kind of mania is frightening. It's just like Jimmy Carter saying, ‘Life is unfair.’ Suffer.”

"I've found that I react to other people's diseases more violently than my own,” says Randall. “I’ve had to become terribly frightened of the outcome, which is only a very destructive process. It's sort of like becoming phobic about your death. Going blind is part of my life process.”

Photo by Benedict J. Fernandez

The Future

Throughout history, there have been conflicting claims about the healing value of marijuana and associated medical benefits. In the second century, Chinese used cannabis as a medicinal herb, given to surgical patients as an anesthetic. Cambodians later administered hemp cigarettes to help relieve asthma. 1850 to 1942, represented the longest period where marijuana was listed in US Pharmacopaeia.

The marijuana hysteria, pushed from the far right swept the country in the 1930s and ultimately restricted further development of marijuana's medical therapeutic potential. The end came with the legal passage of the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937, which labeled marijuana as a dangerous narcotic, no longer acceptable acceptable for medication. We are closing in on century since this archaic ruling. It appears that it is no longer a matter of if, but more when will the drug take on its rightful legal place on the shelves of all pharmacies. When the day comes, lets never forget the pioneers like Robert Randall who took a stand for all of us.

About the Creator

Wendy Weedler

Lives in Washington D.C. Has been part of the legalization movement for decades.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.