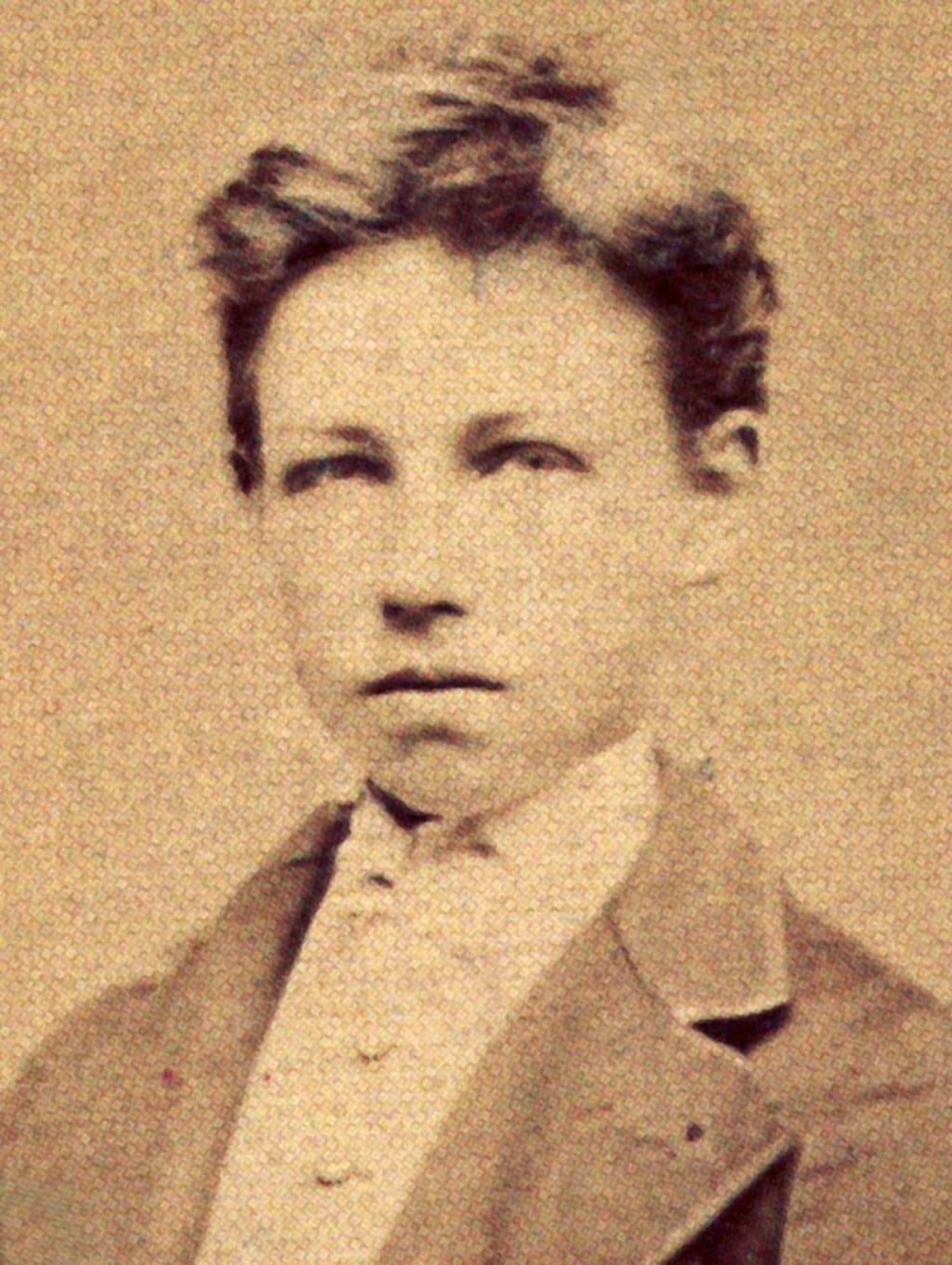

If Sade can be referred to as "the Divine Marquis," then perhaps we could refer to Rimbaud as the "Divine Brat" (Genet might well be the "Divine Wastrel," and Artaud the "Divine Madman"). At any rate, on his 168th birthday, it is meet and good to celebrate this "troubled soul" (as Edmund White so named him).

He was born in Charleville, France, on October 20th, 1854, the son of a soldier who deserted the family, and a stern, severely Catholic mother who ruined him mentally, spiritually; socially. Sexually, he was gay at a time when being gay could see you put behind bars, and he was a child prodigy, who easily passed through his lessons as if sleepwalking and even wrote poetry in Latin.

He had a sister who died prematurely, a brother who cared nothing for him, and was a scoundrel and train conductor, and a sister, Vitalie, who was with him up until his very death. Afterward, she tried to reform him, or at least, his image, in the public perception. He fled home as a runaway to Paris, during the communist revolution, and spent time in the notorious Mazas prison for trying to ride a train without a ticket. Some guess it was here he may have been raped. (However, that is only a matter of speculation with no actual evidence.)

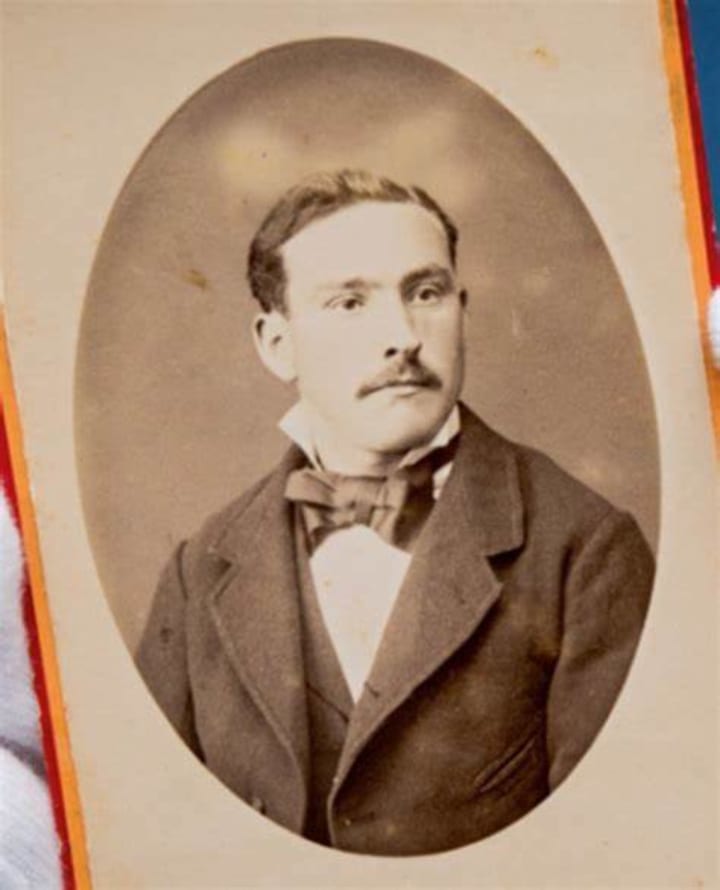

He was often taciturn and could be arrogant. His lover, Paul Verlaine, was a singularly unappealing fellow with a high, bald forehead, thick lips, and wide nostrils; someone once famously commented that Rimbaud's great love "looked like an orangutan." Verlaine himself was a drunken, abusive husband to his young wife, a man who, in a macabre episode, smashed the glass containers wherein the fetuses of his dead siblings were preserved in formaldehyde.

George Izembard, Rimbaud's teacher and mentor, (and, one supposes, would-be protector), convinced the boy-genius to return to Charleville for a short time, but the width and breadth of his literary infamy would be seated in his relationship with Paul Verlaine, with whom he lived and loved in a manner that society looked upon as forbidden.

The two became an infamous duo, drinking absinthe, attending poetry readings, living like bohemians and radicals in an era of coarse and stringent social norms. They scraped by, sometimes giving French lessons in London; at other times, they must have near starved.

Alas, the love affair was not to last. Rimbaud parted from a desperate, frantic Verlaine, meeting him again in Germany. And then Verlaine shot him. Through the wrist, a non-fatal shooting when Rimbaud attempted to leave the drunken, emotionally unstable Verlaine a second time. It was this shooting, combined with his homosexuality, that saw Verlaine to prison for two years. He and Arthur would never reconcile.

Arthur gave up writing at the age of twenty, or thereabouts. His greatest piece (in the opinion of THIS author) "Le Saison en Enfer" ("A Season in Hell") was written while at Charleville, in an old barn. It is, without a doubt, one of the strangest and most inscrutable prose poems ever composed. Rimbaud privately printed an edition, and then quickly lost interest. It was completed, incidentally, in 1873.

From the parting with Paul Verlaine, until his death in 1891, Arthur Rimbaud traveled Europe and North Africa, joining and then deserting the Dutch Army (which could have seen him executed), living among Arab traders, running guns, and finally injuring his leg. This last would prove fatal. The leg was amputated.

A trip back to a hospital in France, to die, is said to have been excruciating. Every bump and grind of the train felt deep within his bones like pain. A "Season in Hell," indeed.

He died raving, with his sister Vitalie near him, finally confessing the Shahada, the Muslim confession of faith ("There is no God but Allah, and Mohammed is His prophet.") and then expiring. At that point, even the morphine seemed to have failed to adequately dull his intense, agonizing pain.

His literary visions were a strange mixture of the inscrutable, nearly opaque and ill-defined, yet bursting, at the same time, with the sights and smells of the livid gutters, the slaughterhouses. These snapshots were put, side-by-side, with a vision of a future world that he could never know: what seems a harsh, impenitent, but furthermore detached motherland where the modern and the cruel or savage, exist as assuredly as the bullet wound in the soldier's chest, in his poem, "The Sleeper in the Valley." These strange, surrealistic glimpses of a future ("It is clear this is an oracle," he claims cryptically, in Season) world, of fantasies of order, are slapdash struck against the rocks of his infernal cynicism, his self-abnegation; his egoism is at war with his monstrous self-loathing; his visions of a strange future he can never know, foreshadowing his early doom.

Satan, who must, "view me with a less irritated eye," is indeed Mother Vitalie Cuif, whose disapproval and disavowal of Arthur, whose eternal indignation and disappointment at her wayward miscreant son, must have loomed large in a psyche infused with guilt, but bursting with images like pieces of ripe, often cankerous or overripe fruit. Puzzling images. Who is, for instance, "the dead girl behind the shrubs," in the poem of the Deluge, in Illuminations? Why does her mother "install a piano in the Alps?" What "language would I be speaking?" (Rimbaud asks himself this, but it is an apt question as to what language he was speaking. Was it the language of dreams and fancy, a symbolic language in which the various eddies and corkscrews of time and scene must be twisted into mental shape, as much as the "colored vowels" he invented?

Rimbaud claimed that he sought a "derangement and confusion of all the senses," inso much that poetry, true poetry, required it. (He notoriously once went to a poetry reading where he spent the evening crying out the word "shit, shit, shit" at the works read by all the other authors.)

A Season in Hell is both self-exculpatory and a confession of guilt, a scathing, harsh, personal plunge into the pits of his spirit. It hums and thrulls with a diseased self-hatred, playful self-mockery; a capitulation to those social factors that condemned his sexuality and choice of lifestyle. His Satan is real and personal ("The demon that crowned me with such magnificent poppies."), and His Satan mocks and condemns.

But the overwhelming guilt he feels is at loggerheads with his own sense of self-righteous, self-aggrandizing prophetic vision. "It is the vision of numbers," he relates cryptically, "adding again, "I am an oracle." He is envisioning a future, not just a literary future, but a future in which modern bestiality and cold calculation exist in a cynical interplay, woven together as a dance of death, for a man that will never see them with earthly eyes.

And he HATES his own being, his fallacious sins, his "inferiority" of the blood, his pagan blood that revitalizes, betraying Christ, whom he assures, if slyly and perhaps dishonestly, "I love my brother...I praise God." But does he?

"What force...has made my tongue so perfidious?" asks this man who has just swallowed a "fabulous draught of poison"? He confesses to living "as lazy as a toad," with some of the best families of Europe; but "families like mine, who owe everything to the Declaration of the Rights of Man." Slyly, with a subtle comic touch, he suggests he's had an affair with all of their eldest sons. "I've known every eldest son in the family!"

These are the blackened leaves out of his "notebook of the accursed." But he tears them off, so that "while waiting for my last sluggard indiscretions to arrive," Satan (Mother Vitalie?) may peruse the great warp and weft of his sins. A Season in Hell is Rimbaud punishing himself, and exalting himself simultaneously. To be an oracle then, to indulge in derangement of the senses, to plume the depths of literary Hell, and to retrieve these glimpses of a fantastical future; all of this is sin as much as it is genius. Or so he seems to confer upon the reader in this masochistic, opaque diatribe.

"I called for the executioners, so that, perishing, I may chew the butts of their guns. I called forth plague, choking on the sand, the blood, lying down in the filth of the gutters. Then, drying myself in the hot wind of crime, as misfortune was my God; I played strange games with madness." --Arthur Rimbaud, A Season in Hell (Personal translation)

Later, during the "Deliriums", we will have a voice that can only be Verlaine's, confessing that he is the wife of an "infernal bridegroom," who, "is really a demon, you know, he's not a man." He followed this man, apparently, when he was still but a boy. He describes him dipping into the alleys of filth, his love that of a "harsh mother" for her striplings. Rimbaud here accuses himself before the demonic forces which condemn him and does so in the voice of Verlaine, whom he may have felt guilty for snatching away from the arms of his own young, long-suffering wife. At any rate, this voice (one of many in the poem) is one of anguish for being a prisoner, a captive (one thinks of the traditional card of The Devil in the tarot, which represents a love that confines and destroys, ultimately) to Rimbaud, the homewrecker, destroyer, liar, enslaver.

His fantasies of embarkation, his contempt for bourgeois values ("You are all false negros..." he chants, perhaps referencing those who, at the time, might appropriate the outward guise of socially-progressive justice, but without actually having any sincerity about it), his hatred of work, his "love of lying and sloth...of magnificent lust", his appeal to "Witches, misery and hate." A Season in Hell is a self-exculpatory confession of guilt from a man bursting with genius and vision, and yet aflame, inside, with impotent rage at the vileness of the mistakes he has made in a life. But it is not his fault, he may maintain.

"I am of the inferior race (Gaulish) forever," he informs us, multiple times. He is a "leper sitting at the side of a sun-blasted wall, amid broken shards of pottery." "If only I had a history going back nobly o the beginnings of France. But no, nothing," he laments. "I am of the inferior race ("Bad Blood") for all time." He seems to say that inheritance has doomed him. In former times he would have "had in his mind routes through the Swabian Plains," made "pilgrimages to the Holy Land," and "slept under German skies at night." But, in the modern world, he feels himself a lying, lazy, and useless whore.

He foresees his own death, describing the coffin, his rage against what Dylan Thomas might call, "The Dying of the Light." Or is this the voice of Verlaine? Is he alternating between victim and victimizer, and who led who astray. This is never made clear.

By the end of "Deliriums 2" we feel the poem has petered out, and has become something that, like an orgasmic climax, is now at a point of savoring. Rimbaud lets us in on his bad, cheap, modern taste, and his passion for work, and reminds us that "he must go whom the Devil drives." And what a trip this Devil has been on.

Perhaps he was never a "Divine Brat" at all; perhaps an infernal one. At any rate, at the age of twenty, he was prepared to shrug off his growing fame and reputation for genius, and confess that he would never write poetry again. When asked about A Season in Hell he would say, "Such books are only good for stopping up the holes in a lavatory wall." He would abandon all literary effort, and, curiously, march forward to an early grave. ( Or, as Edmund White put it, "this troubled soul would be laid to rest.")

Whatever he meant by his "snapshots of the gutter," brewing them, in his derangement, in a heady mixture of fantastical, nearly science fictional vision, and cynical self-condemnation, it is a literary mix still as surrealistically pungent as it is mystifying. The author sleeps now, eternally, rocked like a babe in the cradle of the dust. Behind him, the vision of his life stumbles on.

A Season in Hell (read by Tom B.)

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.