"No Worst, There Is None", by Gerard Manley Hopkins

A poem that expresses deep dejection, written for no-one to see apart from the poet

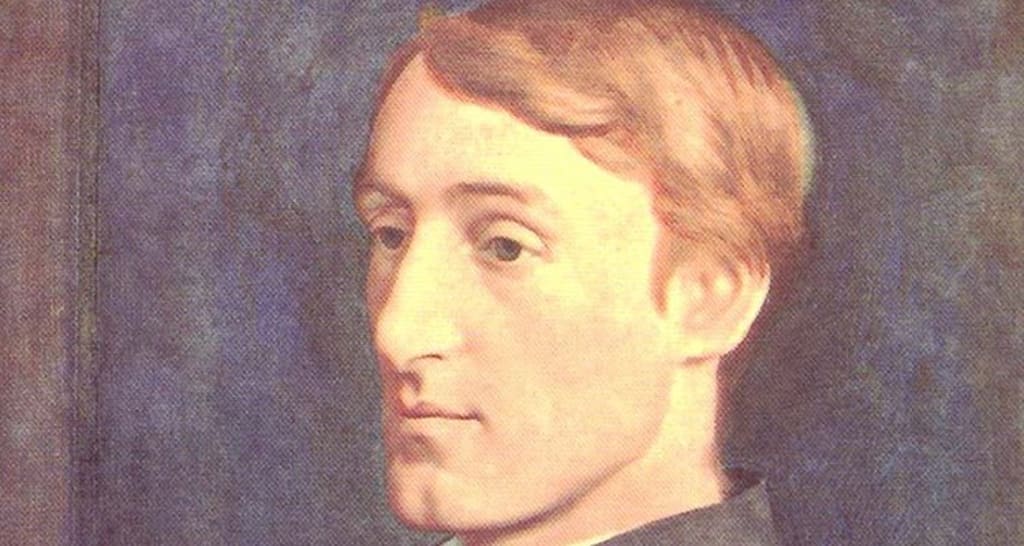

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-89) is renowned today as being one of the most innovative poets of the 19th century, despite only being known as a poet to a very small circle of admirers during his lifetime. His development of poetic devices such as “instress”, “inscape” and “sprung rhythm” only became influential long after his death. He is best known today for poems such as “The Windhover” and “Pied Beauty”, which are celebrations of the natural world, but towards the end of his life (he died of typhoid at the age of 55) he suffered from intense depression and used poetry (intended for no eyes but his own) as his means of coping with it.

The Poem

No worst, there is none. Pitched past pitch of grief,

More pangs will, schooled at forepangs, wilder wring.

Comforter, where, where is your comforting?

Mary, mother of us, where is your relief?

My cries heave, herds-long; huddle in a main, a chief

Woe, wórld-sorrow; on an áge-old anvil wince and sing —

Then lull, then leave off. Fury had shrieked ‘No ling-

ering! Let me be fell: force I must be brief.’

O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap

May who ne’er hung there. Nor does long our small

Durance deal with that steep or deep. Here! creep,

Wretch, under a comfort serves in a whirlwind: all

Life death does end and each day dies with sleep.

Discussion

“No Worst, There is None” is one of the poems that date from 1885 and are referred to as his “terrible sonnets”. This is not a comment on the quality of the poems but a reference to their subject matter, which is the experience of a man going through the terrors of severe depression, which he fears will end in either death or madness. In the case of the sonnet under review, the title, which also comprises the opening words, summarises the mood of the whole.

Hopkins was an innovator with verse forms and the inventor of the “curtal sonnet” of ten and a half lines. However, he stuck to the traditional fourteen line sonnet form for “No Worst”, with a distinct break in sense at the ninth line to form the octave and sestet of the Petrarchan sonnet. In some editions Hopkins’s sonnet is printed with a line break at this point to emphasis the two parts.

Hopkins also stuck to the ABBA ABBA rhyme scheme for the octave, which is the Petrarchan pattern, but for the sestet he used CDCDCD, which is not typical of either the Petrarchan or Shakespearean sonnet.

The sonnet form is often a vehicle for a carefully constructed formal poem in which an argument is expounded as a sort of conservation between octave and sestet. Many sonnets appear to be exercises in verbal dexterity and thus tend to be low on emotional content. It is not the form one might expect for a poem in which the poet is pouring out his soul in a state of despair. However, this is exactly what Hopkins is doing here in a poem that is remarkable for dealing solely with his state of mental suffering and analysing it in painful detail.

Hopkins begins by emphasising the depth of his despair:

“No worst, there is none. Pitched past pitch of grief,

More pangs will, schooled at forepangs, wilder wring.”

Hopkins uses several poetic devices here to achieve his effect. For example, there is repetition (and thus reinforcement) of key words (pitched/pitch; pangs/forepangs) and alliteration in “will … wilder wring”. In particular, the ambiguity of “pitch” is effective in that the word can mean “thrown” and also refer to the level of a note in music (Hopkins was an accomplished musician as well as a poet). There is also the connotation of “pitch blackness”. All three meanings could be relevant here. The general sense of these lines is that the agony of grief is made worse by the pain that the sufferer feels due to remembering his earlier pains (“schooled at forepangs”). This is a highly accurate account of how a depressed person typically allows their grief to feed upon itself.

Hopkins, as a Jesuit priest, would naturally have sought solace in prayer, but in lines three and four he echoes the despairing words of Christ on the Cross (“Lord, why hast thou forsaken me?”):

“Comforter, where, where is your comforting?

Mary, mother of us, where is your relief?”

The following lines continue to build the grief, using some typical Hopkins word-form constructions such as “herds-long” to describe how his cries stretch out like a string of cattle walking past. His griefs “huddle in a main”, with “main” having the double meaning of “broad expanse” and “the most important part”. “Huddle” can also mean either “crowd together” or “drive hurriedly” (as in “the people were huddled towards the exit”).

Hopkins now expands his grief into something that is beyond himself. It is a “world-sorrow” that is “age-old” and in which he is now participating. In trying to seek a cause for his depression, Hopkins is convinced that it derives from the original sin that afflicts all people in all times, such that there is no escape from it. In fact, Hopkins appeared to be suffering from what is known as “endogenous depression” that is an illness in the way that influenza is an illness. There was therefore no underlying cause, but that was not going to stop the sufferer from seeking one. If one is convinced that one is being punished there must surely have been an offence that merited the punishment.

The poet now puts words into the mouth of “Fury”, who: “had shrieked ‘No ling- / ering! Let me be fell: force I must be brief”. It is interesting to note that Hopkins splits the word “lingering” between two lines, which not only allows “ling” to rhyme with other end-words in the octave but also makes the word “linger” when read. This is a good example of Hopkins stretching the sonnet form to fit his poetic purpose rather than allowing himself to be constrained by it.

“Fury” can be understood either in religious terms, as the “God of Righteousness” or as the power of truth expressing anger that is aimed at the evil inherent in the sufferer. The blow that causes the distress must be short and sharp, “fell” in the sense of “lethal” and “force” meaning “perforce” but with the overtone of “being forceful”, which is yet another example of Hopkins letting a word perform more than one function.

The sestet comments on the octave in quieter tones. Hopkins expresses his mental condition in general terms:

“O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. … ”

In other words, the manic depressive condition can produce great highs and deep lows that the sufferer can switch between at any moment. No-one who has not experienced this can properly understand what is going on (“Hold them cheap / May who ne’er hung there”) and the anguish of despair cannot be endured for long (“Nor does long our small / Durance deal with that steep or deep. … ”). Hopkins uses the internal rhyme of “steep or deep” to good effect, especially in conjunction with “creep” at the end of the line, as this emphasises the connection between the highs and lows and the need to “creep / Wretch” into whatever comfort might be available.

At the end of the poem Hopkins seeks relief in the knowledge that “each day dies with sleep” and that this escape from the day’s terrors is always available. However, this is coupled with “all / Life death does end”, and this reference is ironic for a Catholic believer like Hopkins. Just as another terrible day may present itself tomorrow, death will only lead to an afterlife of punishment for the evils that he believes are inherent in him and are the cause of the earthly punishment that he is suffering now. This irony belies the poem’s opening line, because there is indeed something worse than the pain and grief of his condition, namely the everlasting pain that is to come. This fear is only adding to his current grief.

This poem is disturbing and painful to read, because the reader cannot help but feel something of the grief of the poet. It is all the more disturbing if the reader has been through a similar experience, or has lived with someone who has. They will also recognise the extra degree of anxiety that is added when the sufferer has strong religious convictions and believes that they are being punished for their sins.

The comfort for the reader is that Hopkins did recover from his depression during his last years, and that his writing of poems such as “No Worst” (and it must be remembered that they were not intended to be read by anyone else) was part of the self-imposed therapy that helped him to come to terms with his condition and find his escape from it.

About the Creator

John Welford

I am a retired librarian, having spent most of my career in academic and industrial libraries.

I write on a number of subjects and also write stories as a member of the "Hinckley Scribblers".

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.