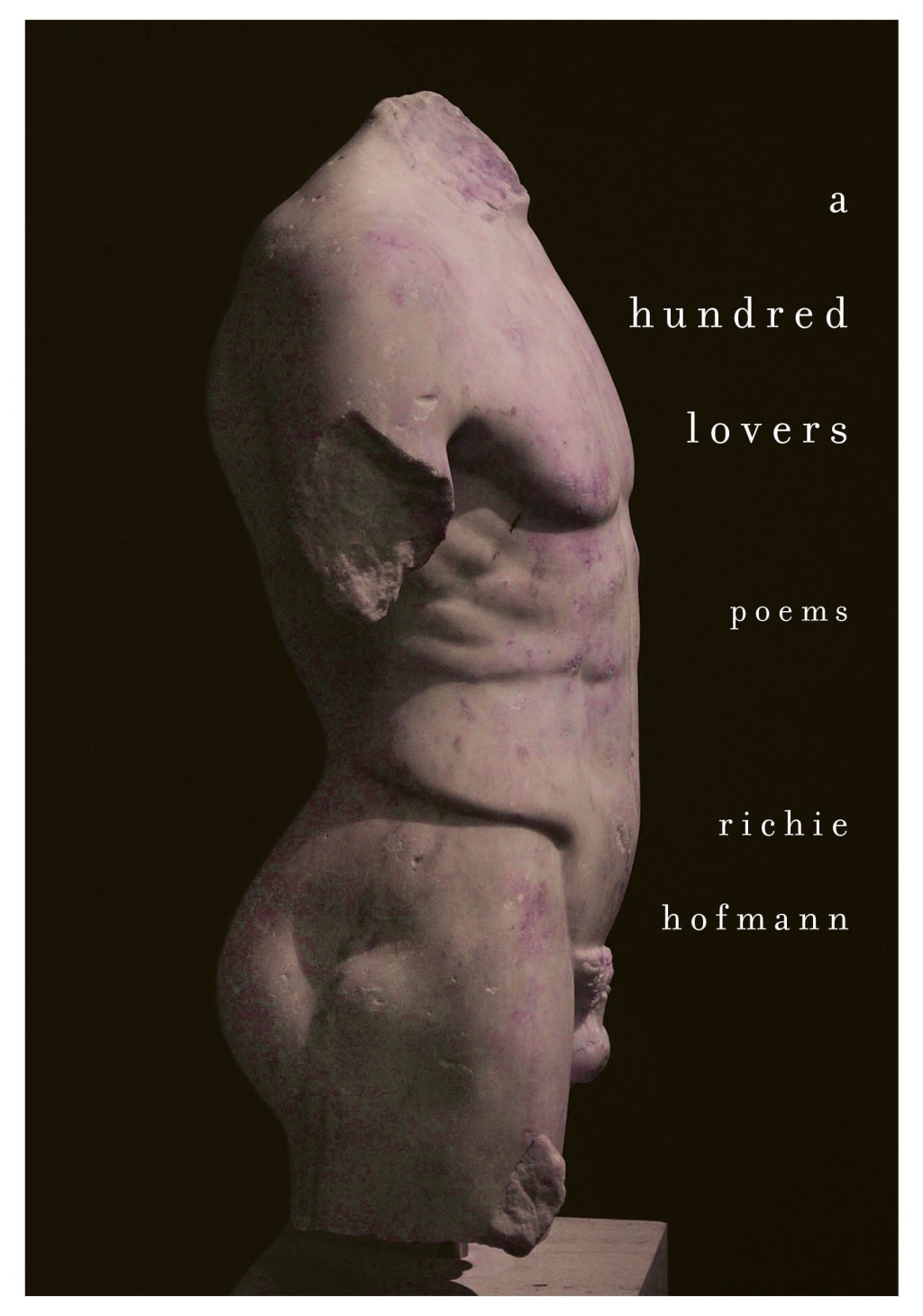

It was nearing the end of the night, a couple of hours after a small coffee with a splash of cream but one and a half until smoking a joint at the bus stop, when Emmy grabbed the book from the streetsmart poetry titles in the back of the bookstore and held it up for me to see: “A Hundred Lovers,” the second collection from Richie Hofmann. It comes out today from Knopf. I hadn’t even heard of it until last week, but only because someone told me about it. Its sudden appearance in my little world excited me. I’d seen the cover online, so I wasn’t surprised by the stunning Greek marble bust of a broken male form, which I did love. The bold insistence of the book’s trumpeted announcement into my sphere and the physical presence of the newly on-sale product was what really captured my attention. I tried to resist, but I had to read it immediately.

I was drawn a few times, just looking at the front and back covers, then flipping through the pages casually before setting it back down. On the fourth time picking it up, I stood still for ten minutes and read it front to back as quickly as I could. I felt several emotions at once. I wanted to love someone, but I wanted to be alone. I was angry at being wanted, and upset at my own desire. I was jealous although I had exactly what I wanted. I was thrilled, I clenched my jaw, and I said something like, “It made me feel things so that means I like it?” to Emmy, who kind of shrugged.

As noted by Doug Paul Case while interviewing Hofmann for Hobart, “I was so happy to see ‘penis' in the poem,” and on the very first page, no less. What struck me about the use of male genitalia as object in the book was that it wasn’t present in an active, sexual way but as distinct sensual, visceral images that took place in the moments after consummated desire has ended. Hofmann’s speaker remembers someone he’s afraid to dream of by the scent of “the T-shirt he wiped his penis with.” The speaker objectifies his own genitals and presents them to the addressed lover/reader as he washes them in the sink. However, this image is not about desire or want, it is about care and fear. How do we remember love when the emotion has passed, and how do we resume the struggle to achieve it once more?

To Brian Wiora of Columbia Journal in 2018, Hofmann described his desire to experiment with “a new frankness about being an ugly human” that was inspired by the exciting work of his students. This honesty and intent felt present in the declarative nature of the poems, as well as the direct address that felt intensely directed at me as I read. The quick and intense interaction I had with the text blurred time and specific details like “masculine lavender,” nosebleeds in the snow, humiliation accompanied by piano music, or gleaming windshields next to parked Vespas began to feel like experiences I could have been a part of. I almost remembered living the poems while I reminisced on my personal history of ephemeral past loves. The dreamy, urgent pull of Hofmann’s poems finally set me down after a week of “Feast Days” that each feel distant in time but connected by the recurring familiarity of a loving but temporary companion that haunts at different moments of the speaker’s narrative. By inviting us into the work as readers, it holds us in an embrace for the short time it can.

The experience of reading “A Hundred Lovers” reminded me of a Shakespearean sonnet, although I was only looking for such an experience based on murmurs on the inner flap that also unabashedly insisted on the nonfictional, “diaristic” aspect of the “erotic journal in poems” that lends an exhibition-like tone to the book and also made me want to dig further. In Sonnet 43, a lover engages with the dream of their beloved versus the reality of the human they have loved. This returned me to the beginning of desire in the “Coquelicot,” the collection’s first poem, when the speaker wonders what will happen next: Will the lover/reader return or will they be satisfied by the singular, undescribed experience that took place outside the bounds of this book? I took a bit of time during the rest of the workday and my commute home to think about it. I think I would really, really enjoy reading this book again. I would relive the dream ten minutes at a time whenever I needed to.

Joe Nasta (ze/zir) is a queer writer and mariner based in Seattle. Joe is one half of the art and poetry collective Eat Yr Manhood with Cass Garison. Zir first book can be read for free on issuu and zir work has been published in The Rumpus, Entropy, PRISM International, Peach Mag, and others. Ze co-curates a zine of unconventional art and writing at stonepacificzine.com and is currently part of the 2022 Collective Autonomous in Practice Cohort with the Operating System/Liminal Lab.

About the Creator

Joe Nasta

Hi! I'm a queer multimodal artist writing love poems in Seattle, one half of the art and poetry collective Eat Yr Manhood, and head curator of Stone Pacific Zine. Work in The Rumpus, Occulum, Peach Mag, dream boy book club, and others. :P

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.