If I cannot recall memories of my mother, I experience a feeling of mourning. As if remembering is a responsibility even though I wonder how much of our memory is actually selective.

“Much like the melancholic body, the photograph refuses to give up the lost object, embalming that which is no longer. In the photograph's magical, and uncanny ability to procreate, there is an unmistakable reanimation of that which has been lost. This moving between imagination and reality, between dream and waking, past and present, mirrors the altering of perception within the process of mourning.”

In Resnais’ film Hiroshima Mon Amour, the character Riva realizes that her memories of her greatest love were starting to fade. The more she tried to keep them alive, the more she kept forgetting. In one instance, Lui (Riva’s lover) says: “I’ll remember you as the symbol of love’s forgetfulness. I’ll think of this adventure as the horror of oblivion”.

Esther Teichmann, whose work touches upon personal melancholia, strongly compares photography and forgetting through Lui and Riva’s relationship:

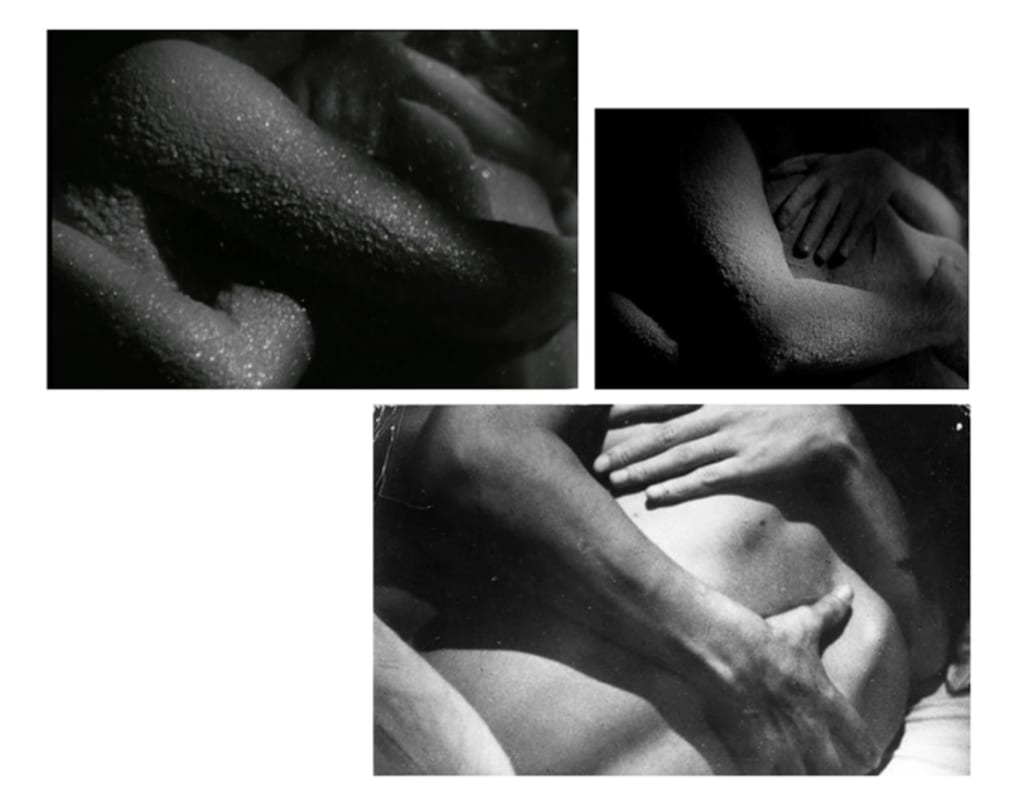

“the lovers bodies cut to bodies suffocating as ash rain upon them, like silent searing snow. Touch, remembering and forgetting haunt this film, as do the depicted subjects, skins and the celluloid medium itself…

The last photograph became her marker of time. For those weeks, which turned into years, she carried that last image taken of him laughing back at her, unknowing contented sleep-filled-eyes, stretching languidly against the morning sun. She wore the tiny smooth square against her skin. Each morning she placed this image against the bottom curve of her belly, just to the side of her hipbone, invisible beneath the layers of clothing placed on top. Each evening she would peel him off, tiny bits of photographic emulsion sticking to her, her skin slowly erasing him, rubbing away and disintegrating his skin day by day. Eventually his eyes no longer looked back and the edge of his body became blurred”.

Fig. 5 Riva and Lui, Stills from ‘Hiroshima Mon Amour’, Alan Resnais, 1959.

The mind seems to re-contextualize memory even when we make excess effort to remember the ‘original’. Ethical forgetting is an important part of forgetting over which humans are powerless to fight. Yet there is another side to forgetting - the so-called ‘desired forgetting’, which Aleksander Luria investigates in his book The Mind of a Mnemonist . The main protagonist has such an incredible memory that he remembers everything. This everything includes what our mind usually remembers and that what it forgets. His memory is stretched and his protective layer dysfunctional. All memories he ‘possesses’ remain on the same level and thus the code for balance is broken. His memories don’t transform his memories are timeless. He is like a time traveller stuck in time.

As humans, we find ourselves in a perpetual process of transformation, whereby our memories will inevitably be perpetually transformed. Some more often, some not at all, some evaporate and are replaced by new ones. There is a balance in our memory, which we cannot control and Marc Auge presents the inextricable relation between remembering and forgetting:

“oblivion throws our memories into relief and gives them shape and definition. Forgetting is an active agent in the formation of memories, and it is because memory and oblivion stand together, are entirely ‘complicit’ with one another, that both are necessary to enable life”.

Following this passage, Anne Whitehead states: “the title of the final section of Auge’s essay calls to mind Nietzsche’s admonition that there is a right time to forget as well as a right time to remember”. She ends her chapter on ‘involuntary memories’ with these words:

“certainly, forgetting seems important to survival itself and can, in addition, work against the solidification of narratives into too static or monumentalized a form. At the same time, however, forgetting cannot simply be prescribed in a manner that overlooks its difficulties, nor should the moral and ethical burdens of remembering be discounted”.

It is those moral and ethical burdens that are precisely at stake for me in this transaction. In this negotiation within my artwork, which brings to light the process of forgetting and mourning, I negotiate a process of overcoming that loss. Almost as if the process of dissecting the photograph that has revealed the inscriptions on my personal ‘wax pad’ has provided a way to overcome the ethical responsibility. Perhaps the dissection itself is the ethical responsibility. Freud mentions that:

“mourning comes to a decisive and ‘spontaneous end’, […] when the survivor has detached his or her emotional tie to the lost object and reattached the free libido to a new object, thus accepting consolation in the form of a substitute for what has been lost”.

Through this process I have discovered that the loss that I was experiencing and the mourning attached to that loss was reconfigured into a sense of guilt. The guilt of producing a loss for my mother. Both my sister and I left home and our mother had to remain in a haunted space that would remind her of our presence and absence. Our mother lived for us and lived through us. She was unable to “detach her emotional tie” as Freud mentioned above. The realization that her libido was not free, that it was oppressed by my father and the ethical responsibility that comes with children, made me feel suffocated by her own so-called love. For me, this translated into oppression. I chose to leave and to forget so that I would not be constantly reminded of that oppression. I chose to leave in the fear that I would adopt the same life. It is hard for me to differentiate whether I feel guilty for wanting to live my own life or whether I feel guilty for not remembering (and contributing to) the life that she had lost. I am burdened with her loss because my existence carries the loss of a life that could have been different for her.

I do not know what is more frightening: losing our future or forgetting our past.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.