MY LIFE AS A BANKER

THE CURRENCY OF CHALLENGE

My Life as a Banker

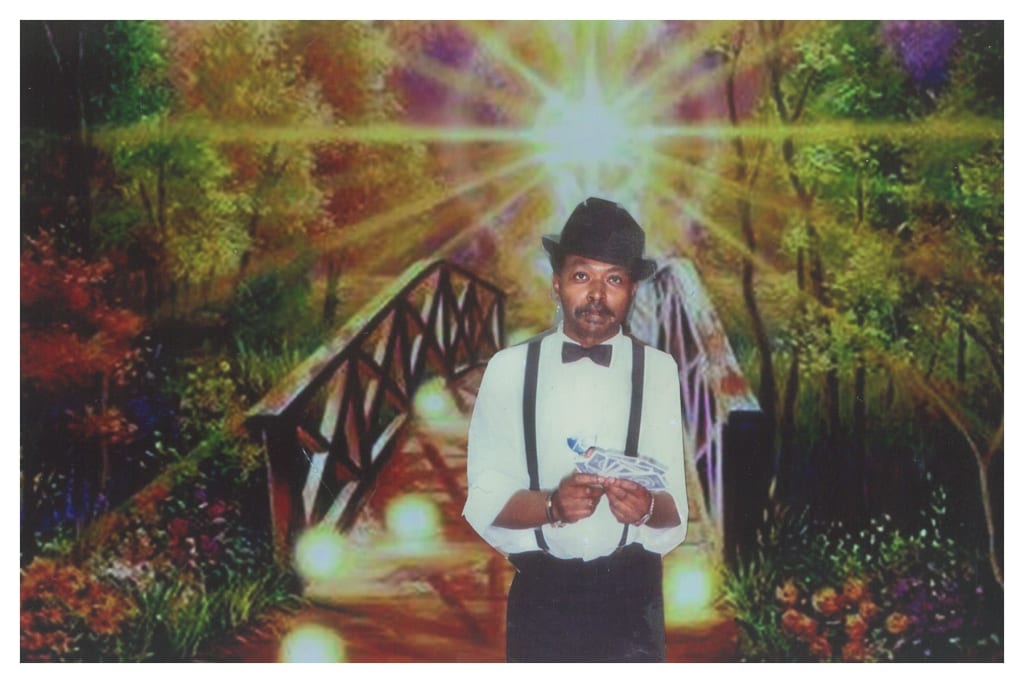

By Frederick B. Hudson

A Parable

One evening when a farmer had cultivated his crops, fed his mule, and locked his barn; he sat down in the evening and watched the sun set. But with darkness came a ferocious rain, followed by wind that whined and gusted with a ferocity that seldom seen.

The farmer told his wife: “I hate this wind—it’s blowing through my corn, some of the stalks may break and the hinges on the barn are rattling, the cows are mooing, it’s frightening the bejesus out of them, the hens may stop laying eggs. I’m going to tell the wind to stop.

His wife knew what type of hardheaded man she had been married to for more than 20 years. So, she pulled down his raincoat and hat, gave him a lantern to swing in his hand, and blessed him as he pushed the door open. She heard him screaming to the wind: “Stop! Stop! I did you no harm! I don’t need this! I don’t deserve this!” The wife heard him bump against the wall of the house several times when her beloved could not stand up. After about two hours, he came inside. His face wore a mixture of exhaustion and relief.

There was a cup of coffee and a slice of apple pie waiting for him on the kitchen table. As his wife lovingly wiped up the beaded raindrops that had collected on the oilcloth table cover, she inquired, “did the wind stop?”

Her husband said no but I screamed so loud that I couldn’t hear myself—so I know the wind heard me.

I dreamed this parable when I tried to place my personal history in the context of the double vision that African Americans see themselves. Often in manhood, I was socialized to believe that in order to have relevance and machismo, my voice had to be loud, threatening, and tough. Otherwise, I was an Uncle Tom. If something wasn’t happening around me that was insulting, I had to invent some offense. Why? Because to be peaceful was to accommodate a world that perceived those of my skin color as wrong. But after many forays into the cage of rage that I constructed, I had to think back to those structures and influences which had been there for me since childhood which only had to be remembered and reiterated for my self-worth.

First, I had been prayed over. Literally. I have strong memories of a guest in the first home I occupied who told my younger brother and me that he wanted to pray with us. I don’t remember his name, but I do recall kneeling and feeling his strong hand on the back of my head as he prayed for God’s grace in guiding me into a safe and fruitful life. This memory is the signpost for many adults in my early childhood in Birmingham, Alabama in the early fifties that nourished my self-worth in a segregated South. The teachers, ministers, and other adults constantly told us that we were destined for great things. Even the schoolbooks we used emphasized our worth, as individuals and as a people.

In Alabama, the “Negro” schools as they were called received separate textbooks in many cases. Though the books were often worn, since they were destined for only dark-skinned youth, the Board of Education often allowed books into the curriculum that took a very, very positive view of the Negro people. I have vivid memories of one book that told the heroic story of a Negro youth who saved an entire dormitory by making many trips up and down the stairs to ensure all his classmates were safe. What a role model!

The first elementary school I attended was a one-room schoolhouse in rural Alabama called Thomas Furnace School—it was so named because of its proximity to a furnace that was the primary source of employment for many of many classmates’ fathers. Many of my friends came to school barefoot at times but the warmth and regard I found there exceeded any academic environment I have ever graced. Why? Because each one taught one. The second graders helped the first graders. The third the second graders and so forth. I had to stumble through years of frustration with classes in later “integrated” and “better” environments without remembering the simple lesson that the best way to remember anything and see new meanings in any material is explain it to another.

Later, when I was on the staff of a business college, I used this technique when I was asked to take charge of as many as three separate classes at the same time. I remembered how Miss Cole and Mrs. Smith did it. They said: :” you are in charge of helping these people learn—I will be back to check up on you—but you are responsible”. In that environment, there is no room for a negative peer group dynamic so often depicted on television as contributing to a “blackboard jungle” environment. We were all peers in instructing and learning.

Second, I was told to prepare for and welcome change. I was a youth in the era in which the schools were being integrated and the historical impact of each attempt of our neighbors to make a better world was discussed with great fervor and detail. Our role as citizens was outlined as a shining globe that could mirror infinite achievements. Sorrows and misgivings had little place in this brave new world that our elders were making and the participation of youth our age in the boycotts and demonstrations made our understanding very salient.

But my family moved to the “more liberal North” when I was ten, and confusion set in. The white teachers did not appreciate my abilities—they placed me in the lower ability sections in all subjects even though I had scored four grades above grade level in all subjects on national norms in all subjects in Alabama the year before. I journeyed from confusion to frustration to antisocial withdrawal.

Even spiritual institutions left me with a bad taste in my mouth since the only Presbyterian church in our town was white and the Sunday school experience left me with a distinct feeling that God was not present in those rooms.

My relationship with my peers was distant because they seemed consumed with fighting and sex and had very little curiosity about any higher levels or attainment. I was a mess.

My outlets were reading and television. I developed a rich fantasy life and mimicked actors on television. Yet when I tried out for the school play, the only role, which a Negro could conceivably play in a drama in which most of the characters were members of a white family, was that of a banker. The person casting the play was impressed with my portrayal, I was asked to come back time and time up to the final audition, but the role went to a white lad. This youngster kept missing rehearsals and I was told that the cast asked that I been given the role, but the socioeconomic forces could not accept seeing a dark man coming into the home of a white family as a banker, not a servant so I was never called back. I thought back to my earlier years in Alabama when I saw movies in theatres with all black casts and resolved that I would act again on some screen and some stage.

So I was angry. An emotion that the white society has great difficulty accepting from a black youth, particularly a male. I rebelled, sometimes positively when I wrote a petition in strict Constitutional format, advancing the cause of the ninth grade class being allowed to see an assembly that they were being excluded from because of space limitations. A friend and I coordinated the distribution of the petitions in all the classrooms and presented the petition to the principal. Thus, the lessons I had been exposed to in the Southern civil rights movement had their outlet. The principal responded to my initiative by saying: “this is how Communism starts.” Strange since the bill of rights which I had to memorize the past year seemed to identify freedom of speech as one of the pillars of this democracy we inhabited.

My real self-actualization came in college when after a lonely freshman year when I sometimes went into the bathrooms and set the wastebaskets on fire (this was my own burn baby burn! act months before the Watts riots), I obtained a summer job as a mail carrier in the summer of 1964. I had the opportunity to talk to many diverse types from car washers to disc jockeys as I handed them their mail. I noticed the broken family syndrome in the black community when I delivered many child support checks. I resolved there was no point in going through life looking at the world as if it was a television screen. I was going to play an active role.

The next September, I plunged into student politics and writing, obtaining leadership roles fairly quickly. I read Malcolm X’s autobiography, identifying with his frustration since the town which hosted many of my frustrations after coming “up North” was the same one, Lansing, Michigan, in which he was told to become a carpenter rather than attempt the legal career he aspired to. I felt that school was no longer it right then. I joined the Volunteers in Service to America, determined to take on the despair of the ghettoes.

I also joined the Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee, meeting Stokely Carmichael and other international figures. But there remained a deep void in my soul; despite all the rhetoric I dispensed—the undercurrent of hatred was not building self-esteem in those who chose activism. Where was the eternal goodness, where was the peace that passes understanding I had heard of as a boy?

I read philosophers, notably Albert Camus, whose meditations in The Myth of Sisyphus stride nobly from contemplation of suicide towards acknowledging the hills and valleys of spiritual quests in search of beauty and truth. These were visions that seemed illusive butterflies while the Nobel Prize winner watched his native France exploit Algeria, a third world country. Camus concludes that the thoughtful soul is destined to accept the weight of conscience that seems unfairly heavy as worthy cost for the benefit of constantly relearning that which he already knows. Similarly, The Prophet, by Lebanese poet Khalil Gibran helped me understand that wisdom come in spurts, that the faucet is never fully open or closed. The mystic, he says, should: “say not I have found the truth but rather I have found the truth wandering upon my path.” I have often felt Gibran’s hand on my head in moments when rage was the nearest disciple.

My personal path has taken me to roles as community organizer, therapist, teacher, administrator, urban planner, actor, poet among others. I am fortunate enough to have lived long enough to see many black men who I have known in other roles become writers, scribes who dispense their wisdom before their time on the planet has expired. These men have much to teach us in the ongoing debate about the perceived pathology of the black male which underpins much of the conservative movement in American politics. Viewing black families as being beyond rehabilitation, some conservatives think of children from troubled homes as essential “orphans,” children whose parents are virtually dead, and advocate their placement in institutions.

This viewpoint is belied by the reality that America in many instances refuses to see a male of African descent. It is no accident that arguably the most acclaimed novel of the twentieth century with an African American protagonist is called Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. You don’t have to be lynched, you can just be ignored. I was when I tried out for the school play, when I wrote the petition.]

In November of 2000, I was asked to join a task force of activists, scholars, and organizers in developing a meaningful curriculum for South Africa. I was overjoyed that the cycle of seasons’ sacrifice had evolved to allow me to participate in such an undertaking.

However, the day before the first brainstorming session, I read in the New York Daily News that an elementary school principal was being censored for making the remark that there was no point in asking the Polaroid Corporation for donations since “children of color don’t photograph well for Polaroid!” I guess the photographic giant would be happier with a shot of the building and the empty playground rather than see youth with the complexions worn by a majority of the world’s nations. I wondered if my own country needed me more than South Africa. If the camera lens should not focus on a people, then it seems obvious that the human eye straining for focus may well be repelled by a “different” human face.

Frustration feeds failure. Ignored men, women, and children make poor neighbors, friends, husbands, employees.

One of the most ardent current advocates for presence on the world stage for the black man is Harry Belafonte. Although the entertainment industry discovered he had significant acting talent-he turned in a bravura performance in Carmen Jones in 1954, playing opposite Dorothy Dandridge--he has turned down many scripts. One of the most noteworthy was Lilies of the Field-the film and the lead role that gave Sidney Poitier his Oscar. Harry simply could not accept the black protagonist appearing in a field of lilies with no history or passions of his own; a man with no ambition but to help some white refugee nuns. The character had to have a home.

I am privileged enough to have lived long enough to see other actors achieve financial success and take on other roles in the society. Actor Wesley Snipes chose to produce the wisdom of Dr. John Henrik Clark in a documentary a few years ago, that told us of our spiritual home in Africa.

In the film, A Long and Mighty Walk, Clark addressed all the frustrations that beset my adolescence and adulthood by sharing the central concerns of humanity and identity as searching for answers to central and life-enriching questions. Those questions are “how will my people stay on this earth, be educated, be schooled, be housed, be defended?” He saw the answers to those questions as creating concepts of enduring responsibility for us all.

He has provided those reference points that amplify an ancient Ethiopian civilization where there were no words for jails, for orphans, for old folks’ homes because all contributed, all were cared for.

The distinguished poet Robert Hayden wrote in his poem, “Frederick Douglass,” of “visioning a world where none is lonely, none hunted, alien.” I want to be a banker in this play of history; the currency is concern, the integers are heart and spirit, the vault is eternity.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.