Find Your Past In A Pair of Scissors

Memory is always moving forward. Crafting can help us find the past.

This is the story of how I found my past in a pair of scissors.

We’re driving through the dark, coming down through Virginia and into North Carolina. Behind us is everything I have ever known: my Canadian childhood veiled in snow, lake water, fog horns, river locks, the warm scents of Italian food, the click-click-click of my grandmothers’ sewing machines.

Ahead of us, flitting one by one past our Dodge’s brights in a dark pageant: a rosary of American uncertainties. Hot, humid summers. Paper money made of soft, green cloth. Sultry green trees with leathery leaves drooping over the road. Children with Southern accents who won’t understand a word I’m saying. Public elementary schools at which, at best, I’d be left to fend for myself.

Everyone creates their own story, and every story is a collage of imperfect memory. We can find joy in this creation.

Driving to North Carolina from Sault Ste Marie, Ontario, I would soon begin creating a self-story inspired by painting and scissors.

Leaving Canada

Rolling down the highway, I’m sketching the hills we pass. The speed of our Dodge Caravan skews their shapes, and I produce elongated swells of earth that don’t look much like the real thing. I’m still a kid and I don’t have much of a notion of what it means to see accurately—yet.

I want to take the sketches to our new house in North Carolina to transform into watercolors. But when we get to our new two-story house in Chapel Hill, NC, and I finally get my art supplies set up in my new room, I get quickly frustrated. It’s not coming out right. I’m trying to transfer my sketch to the watercolor paper by eyeballing it, but things look different here. Relative sizes aren’t making intuitive sense. Something about the way I view the world has changed.

For the first time in my brief life as an artist, I’m getting frustrated at my inability to see.

Because transferring a sketch to the canvas is difficult. Maneuvering the thing you made in the moment to the artificial surface on which you’re trying to produce not your impression of the thing you had at the time, but the truth of the thing as you see it finally is ...

... freaking hard.

Eyeballing It

Barely anyone can actually eyeball proportions. It’s like the visual arts equivalent of perfect pitch. Sure, you can train yourself to understand bodily proportions, just like musicians can train themselves to understand how musical notes relate to each other—but absoluteness is a different story. For absoluteness, you need tools.

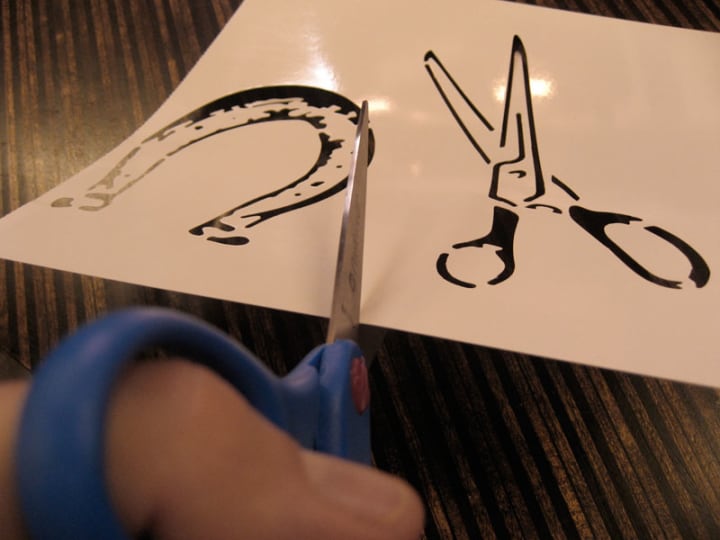

For example, scissors and paper.

But 12 year old me doesn't know this. He's sitting before his easel by the window overlooking his new street, a thousand miles away from home, crying because those mountains that took him away from his home won't reveal their shapes to him.

And he's unhappy, because he's trying to do it all by himself.

North Carolina

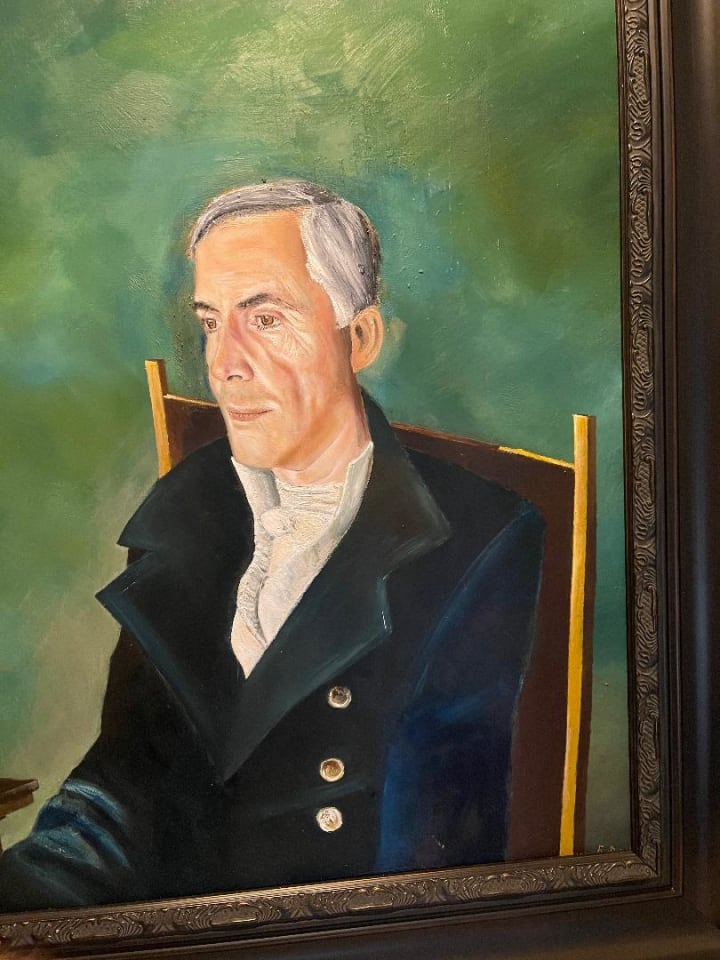

During that first summer in North Carolina, both my father’s parents died. First my Italian grandfather, from whom Parkinson’s Disease had already robbed his voice and mobility. Then, less than a month later, my French grandmother, felled by a stroke.

Two more links with my home were gone.

I tried to draw their portraits. Having long since learned that freehand portraiture yielded only warped, disproportionate imitations, I placed a sheet of paper over the computer screen on which I’d uploaded a picture of my grandparents and traced over their features. Then I filled out the sketch with details, and once more tried to transfer it over to my canvas, in paint.

It was now that I got the idea to use a stencil.

I grabbed a pair of scissors and, against my instinctive need to protect my artworks like children, cut around the perimeter of the sketched portrait. I placed this simple stencil outline on the canvas and filled in the head-shape with paint. While this was drying, I carved up the sketch even more to create stencils for the placement of the eyes, nose, lips, et cetera. These I put inside the head outlines as carefully as I could. Down to the millimeter. Finally I ended up with an accurate skeleton for a painting.

Dismantling A Lie

This is cheating, I thought. You’re not supposed to use tools to remember. You’re supposed to just be able to do it.

As I sat by my easel looking at this cheated artwork, at this irrefutable evidence of my shortcoming, I felt my memory of my grandparents’ faces start to slowly fade.

Memory is always moving forward, like a car down a new highway. The things we pass stretch and distort, and nothing is remembered the way it happened. We use tools to remember: our friends, family, the written word, photographs, home videos, even arts and crafts to construct our world of memory.

A pair of scissors can help us come back to a cherished time. Using a stencil is not cheating. Not anymore than using a paintbrush instead of your finger is cheating.

But 12 year old me bought into the lie that help—even if that help comes in the form of paper and scissors—is cheating. That you should be able to "just do it." That the truth should be bursting from your fingertips unfettered by skill level. A genius, in other words, doesn’t need to create a stencil.

What a dumb kid I was! Why did I think this? Was it overcompensation for the feelings of powerlessness that come from displacement? Or does it boil down to Western rhetoric about technique and genius? Both?

At any rate, I was making a huge mistake: I was devaluing crafting and overvaluing pure technique. By doing this, I was setting myself up for failure.

When it was remarked that Shakespeare never blotted out a single line in his manuscripts, his theatrical rival Ben Jonson was supposed to have retorted, "Would that he had blotted a thousand!"

Crafting Is Essential In Art

Pablo Picasso, the unimpeachable face of “serious” art in the 20th century, was not averse to cutting up fragments of newspaper and pasting them onto canvas. For most of the history of film, the snip snip snip of scissors could be heard coming from the editing room. The engineers cutting tape in the editing room for the latest Beatles album were some of the most important hands on deck. You can find crafting where you least expect it.

You can find crafting where you least expect it.

I’m embarrassed by how long it took me, but I eventually embraced the confluence of crafting and what I’d thought of as “higher” art.

A mistake helped me do this.

The mistake happened in middle-school art class, probably a year after our move. We were doing an activity in which we were supposed to use a grid-system to transfer an image from a National Geographic to a sheet of paper. You probably did something similar at some point in your own art classes: draw a simple grid on the image, reproduce the same grid on your paper, and transfer (freehand) each individual square until you’ve got an image that looks very like the original.

I loved the idea of this. My mind went back to those mountains, elongated and distorted by the speed of my passage into this new world. I thought also of my grandparents’ faces. And this wasn't "cheating;" a grid was a practical technique I could do with the same pencil and straight-edge I was using anyways.

I eagerly drew my two grids and started drawing. But lo and behold: I messed up. I’m not entirely sure how I managed to get such a simple task wrong, but by the time I’d finished I found that part of my drawing was totally warped! Most of the face I’d been trying to recreate was correct, but a chunk of the cheek was all wrong.

Of all my new teachers, my art teacher had the strongest Southern accent. She and I could barely understand each other, so I didn’t like having individual exchanges. But when she walked by my drawing and saw my hanging my head dejectedly over it, she made a simple suggestion.

“Just get some paper and glue and do a little plastic surgery.”

“Plastic surgery?”

Just cut out a new piece of paper in the shape of the part that you messed up, she said, and glue it on. Then try a second time over that.

But that’s… cheating! I thought. Since it was just a class assignment, however, I decided to follow my teacher’s suggestion despite my prejudices against crafting. I grabbed a pair of scissors, cut out a new piece of paper and glued it onto the problem area. I redrew that part of the grid, and this time I got it write. Looking at the finished drawing, you’d never know that crafting had helped me finish it.

And I felt joy! Immense joy at having gotten it right. Joy at having accessed the "truth" of the original drawing.

Now, having allowed myself to use scissors and paper, a whole new world was open to me.

Today

Skip forward 17 years.

I’m painting a portrait of my father. I tape a piece of paper to the computer screen and trace carefully over a high-resolution picture of his face. Using a pair of Fiskars, I turn this into half a dozen stencils and carefully use them to transfer him to the canvas.

Memory is always moving forward, like a car down a new highway. Nothing is remembered the way it happened. But someday when my father is gone, I will have this painting to remember precisely how he was—or, at least, how I saw him.

I'm never more joyful these days than tracing around an image of a face, using my scissors to create stencils, and using the stencils to transfer the face to the canvas. It feels so good to get to the thing.

Let's outgrow the genius narrative. Let's take joy in dismantling the idea that technique is all-important, that Shakespeare never blotted out a line, and that tools are cheating.

Because it's all tools. It's all do-it-yourself. And it's all crafting.

Go ahead and find out for yourself. Find your past in a pair of scissors.

About the Creator

Eric Dovigi

I am a writer and musician living in Arizona. I write about weird specific emotions I feel. I didn't like high school. I eat out too much. I stand 5'11" in basketball shoes.

Twitter: @DovigiEric

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.