We didn't drive over the bridge. This surprised me. I remember thinking we would see the spire of the Pan Am building piercing the fog, or the bay shining in the distance. However, on my first visit to San Francisco in the 1980s, we took the tunnel. The Bay Area Rapid Transit train from Berkeley spat us right into the loud reverberations of the downtown business district.

It was 1984, the city of San Francisco was on the brink of collapse, AIDS was a full-blown crisis -- and the Reagan administration was humiliating and mocking its victims. When my family walked down Kearney Street, people stopped us every few steps. Men in rags begged us for money, food, anything. Today, the city is still destitute, and the river of technology wealth flows only around it. As a child, San Francisco felt apocalyptic. How does a city pretend it's not falling apart?

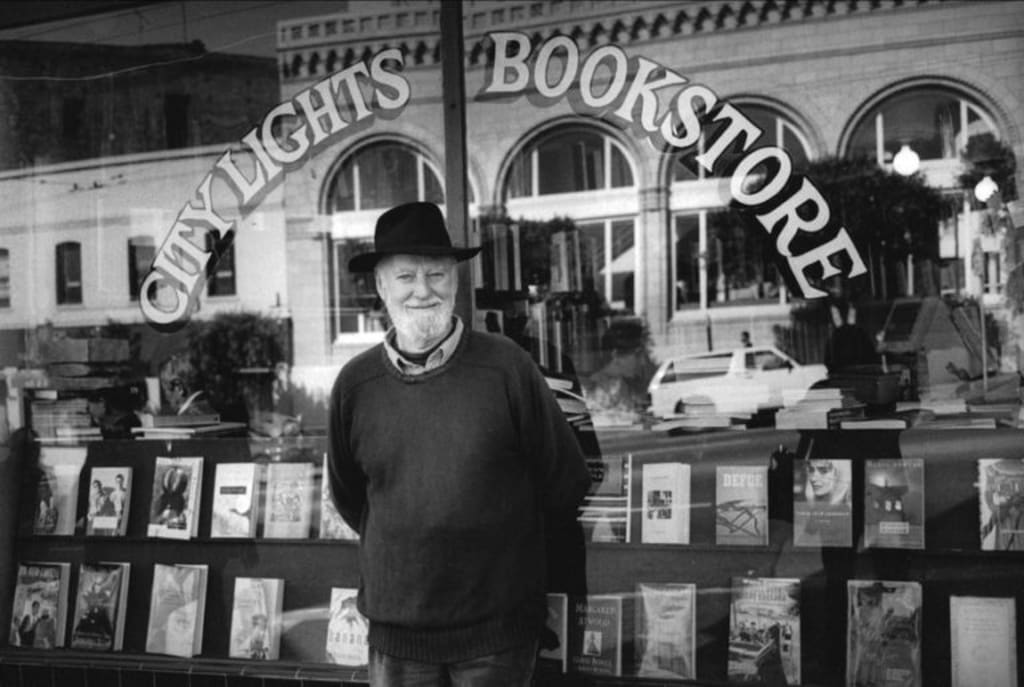

We stumbled into a bookstore at noon. City Lights Bookstore, an oasis in the middle of a desert, sits on the corner of Columbus and Broadway. I remember thinking as I walked through the door that it had a very unique idea of what kind of water we all need. Books on revolution, how North America was stolen and community action fill several shelves. There's a whole floor of poetry. I was only ten years old, but my parents were both radicals, so I could already recognize the tribal insignia of left-wing thought. Wherever you look, you can see the city's plight, in books, on bulletin boards, in one-page poetry flyers handed out, in plastered slogans on bookstore walls. I've never seen a place quite like this one by showing you how to get out of trouble by re-engaging actively in society.

That was 37 years ago. Today, in the midst of the plague, bookstores are still open and thriving. But yesterday, it lost one of its ever-fashionable 101-year-old founders, poet, publisher and community activist Laurence Ferlinghetti. No other American writer has resisted power for so long as Ferlinghetti. As a poet, bookseller and publisher, he fought the powers that be. The poems in his collection, Coney Island of the Mind, awakened an entire generation to the realization that America's military-industrial complex was a nightmare.

At City Lights, America's first paperback bookstore, readers can find their way around at a low price. City Lights Books' books include Allen Ginsberg's Howl, Rebecca Solnit's first book, and a recent book on drone strikes. No other brand in American publishing has explored the moral values of the imperial age so deeply.

It is now, to some extent, fading into history, if we are to judge by the celebration of Ferlinghetti's 100th birthday nearly two years ago. City Lights Bookstore has been a mecca for young people for a long time. Yet on that Sunday afternoon in 2019, the store was packed with people in their fifties, sixties, seventies and beyond. Many men wore hats -- bowler hats, woollen sailor hats, fedoras, berets, even cowboy hats. Hardly anyone under thirty turned up. The day's festivities began with an enthusiastic opening speech from bookstore manager Elena Katzenberg.

It began with a ferlinghetti poem read by Michael McClure, 86, one of five poets who took the stage in 1955 at the famous Six Galleries Poetry Reading, often seen by critics as the beginning of the Beat movement. The other four poets are Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Philip Lamantia and Philip Warren. Ferlinghetti published all of them in the bookstore's Pocket Poets section. Next, 85-year-old former San Francisco poet laureate Jack Hirschman read ferlinghetti's greatest poem, "The Sea," including the line, "He kicked Death in the ass at the age of ninety." Hirschman has the voice of the old sailor.

For the next six hours, North Beach -- a still scruffy neighborhood filled with strip clubs and Italian bistros, and the location of City Lights Bookstore -- is a day-long celebration. I strolled into the Peepshow cafe, just down the street from the bookshop, and heard Sam Sachs, one of America's most exciting young poets, read Ferlinghetti's brilliant poem "The Dog," which tracks a dog's tracks through the city, "It looks/like a living question mark/into a bewildering existence/this huge record player/with a wonderfully hollow horn on it."

Inside Jack Kerouac Lane, a group of actors is staging an interventionist play by Ferlinghetti written in the 1970s. Robert Haas, a former POET laureate of the United States who lived in Berkeley, said that having Ferlinghetti in the Bay Area was like having a benevolent sun that always shone and made it possible to see clearly. Ishmael Reed and Paul Beatty were also there, but they were just watching from below. As the weather warmed and more young people showed up, the bookstore became what it had always been -- a heart with many ventricles, pulsating and pumping out light and new ideas.

Ferlinghetti was not present. Shortly after sunset, the bookstore staff sang happy Birthday to him as a group and across the street from his apartment building in North Beach. He went to the window, dressed as neatly and fashionably as ever, wearing a red scarf, and beckoned downstairs. For a man at the center of things, he was always a little uncomfortable and wanted to step aside from the spotlight -- he preferred to play the role of reflecting the light.

You can see that in his work. "New direction" publishing house published a few years ago the fehling getty's greatest poetry covers over 60 years of his astonishing creation, and no matter where you open the book one page, can see his brush strokes from the era of the world's most dark events - the Vietnam war, climate change caused by ecocide spread - writing, finally returned to the light and the light. Like Walt Whitman, Ferlinghetti wrote poetry in long blank sentences, but his "I" was softer, stranger, and less chatty. His long lines that stretch from page to page have sudden, well-timed pauses that allow him to switch notes abruptly, taking poems into emotional orbits of warmth, wonder or mourning.

The magic of Ferlinghetti's work lies entirely in these inflections. They make his politics never the hinge around which the door of a poem turns, but something larger and more eternally human, even hopeful. The poem "Two scabs on a truck, Two beautiful People in a Mercedes" brings two opposing social classes together at a traffic light and sees a glimmer of optimism in this sudden juxtaposition, "All four close together/as if indeed anything was possible/between them/on both sides of the cove/on the high seas/in this democratic country."

The long disconnect between modernism and confessional poetry in America has made it hard to locate someone like Ferlinghetti. Though he admired The Waste Land, unlike T.S. Eliot, Ferlinghetti was deeply offended by the idea of "art for art's sake." And, unlike confessional poets such as Sylvia Plath and Robert Lowell, he was also sceptical of the personality, the ego and mythlogizing.

It was his experience in France that enabled Ferlinghetti to find his own path between these two extremes. He went to France on gi Bill money to get a graduate degree at the Sorbonne, where he read in great depth surrealists like Andre Breton and Antoine Aalto, whose work he later published in the United States. He also read the work of Jacques Prevel, whose Words, published in 1948, was first translated into English by Ferlinghetti and included in the Pocket Poets series. Prewell's playful realism, his rhythmic riffs, as in "Sunday" (" Remember Barbara "), and his warped conception of what is "real" have also become hallmarks of Ferlinghetti's work.

Recently, when Dwight Garner of the New York Times asked him about the Beat Generation, Ferlinghetti said that the only committed surrealist among them, William S. Burroughs is the best writer of his generation.

Ferlinghetti's affection for Burroughs stemmed not only from artistic admiration but also from the fact that the two were contemporaries. The two were born a decade before Ginsberg, Kerouac and Snyder. Ferlinghetti was born Lawrence Ferling in Yonkers, New York, in 1919 and sent to France as an infant. His father had died, and his mother had been institutionalized in what was then called a "lunatic asylum." (He later reverted to the family name.)

Ferlinghetti only began learning English when she was five and returned to the United States with her aunt. He was raised by his aunt in suburban New York, where she worked as a governess in a wealthy mansion. She abandoned him and sent him to live with other family members until, after the stock market crash of 1929, he was adopted by another family who once caught him stealing and sent him to boarding school.

Though technically orphaned twice, he eventually earned degrees from the University of North Carolina, Columbia and the Sorbonne, just as the cultural capitals of the world were moving from France to the United States. Driven by patriotism, he fought overseas: he was captain of a submarine by D-Day in World War II. But when he saw the devastation caused by the atomic bomb, he immediately became a pacifist. Like many other expatriates, he has been away from home for so long that he has gradually changed his regional identity. "When I came to San Francisco, I still wore my French beret," Ferlinghetti told me with a laugh in an interview. "The Beats came later. I was seven years older than Ginsberg and Keruak, and all of them were younger than me except Burroughs. I got involved with the Beats when I published them."

Looking back through the telephoto lens of history, Ferlinghetti's achievements as a publisher may well lie not only in publishing the Beat generation, but also in publishing younger and newer writers. Over the past 60 years, a large number of black marxist (such as Bob kaufman), Latin America against poets, such as Daisy, zamora, ernesto, cardan,), the young and fashion writer of short stories and novels, such as Rebecca brown, li da du kang), as well as the works of some of the left-wing thinker, Were published through this Columbus Avenue publishing house. For many readers, it was the Pocket Poets series that first introduced them to Frank O 'Hara (Lunch Verses) and Danes Levotov (The Here and Now), not to mention the great Bosnian poet Semizdin Mehdinovic (Nine Alexanderia). To this day, you can buy all these poems at City Lights Bookstore.

Ferlinghetti became a bookseller almost by accident. A friend of his, Peter Martin, had started a literary magazine called City Lights (named after Chaplin's film) and needed some income to keep it going. Martin suggested a bookstore, and Ferlinghetti liked the idea, because he had just returned from Paris, where the banks of the Seine were dotted with street stalls selling books as if they were bread. It turned out to be a shrewd business decision. City Lights bookstore opened at a time when the paperback revolution was in full swing and the city was filled with avid potential readers.

"We filled a huge gap in the market," Ferlinghetti once said in an interview with the New York Times Book Review.

City Lights Bookstore was the only place in the neighborhood where you could go in and sit and read without being constantly urged to spend. That was one of Ferlinghetti's intentions when he started it. I also felt that the bookstore should act as a center of intellectual activity, and I knew that this was also the natural mission of a publishing company.

While some beatnik poets drank too much and squandered their talent, Ferlinghetti honed his poetic skills. The jazz-free, gritty rhythm of "Coney Island of the Mind" is a call for resistance in an age of unchecked American power.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.