The World's Toughest Sport

Where men and women compete on equal terms for 100 days 24/7

Alone. Up to a hundred days at sea, through the world’s roughest seas and strongest winds, passing the Three Great Capes, men and women competing as equals against nature and each other. Non stop. That's the Vendee Globe.

It's big business with top name sponsors and elite sportspeople. Yacht racing is their day job. Night too. Their careers.

It's the world's toughest sporting event. Without doubt. Here's why, with a bit of background thrown in.

Man v Woman — a Rarity in Sport

It’s rare to see a physical and mental endurance sports event where men and women compete on equal terms, but the Vendee Globe is one. And I think it’s the toughest sports event in the world.

The gruelling race sees competitors circumnavigate the globe, solo and non-stop, in some of the most extreme conditions on Earth.

Although I’m a sailor, sailing round the world, I’m not big on racing (I’m a watcher) but the Vendee Globe is more about the personal challenge. It’s difficult and it’s dangerous. I’ve done three Atlantic crossings and one Pacific crossing in my own boat — with one or more crew.

The longest non-stop distance I’ve sailed solo is 1,200 nautical miles in the Atlantic. That was not too bad, but the thought of over 24,000 miles solo through the toughest seas and weather in the world is something I could never contemplate.

Especially with only myself to talk to. And my dog.

How times have changed

The race that kicked it all off was the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race in 1968–69. It was riven with controversy, several sinkings and retirements, and one suicide. Won by Robin Knox-Johnston, he took 312 days to complete the course and was the only finisher out of the nine entrants.

In the 2020 Vendee Globe Race, Clarisse Cremer, the 31-year-old French skipper of Banque Populaire X, sailed across the finish line of this 9th Vendée Globe in 12th place. She went down in the history of circumnavigation completing the course in a shade over 87 days - the fastest woman round the world.

First position was taken with a time of 80 days. Yes, around the world in 80 days (though other solo sailors have completed the course even more quickly, but not in the Vendee Globe as far as I am aware).

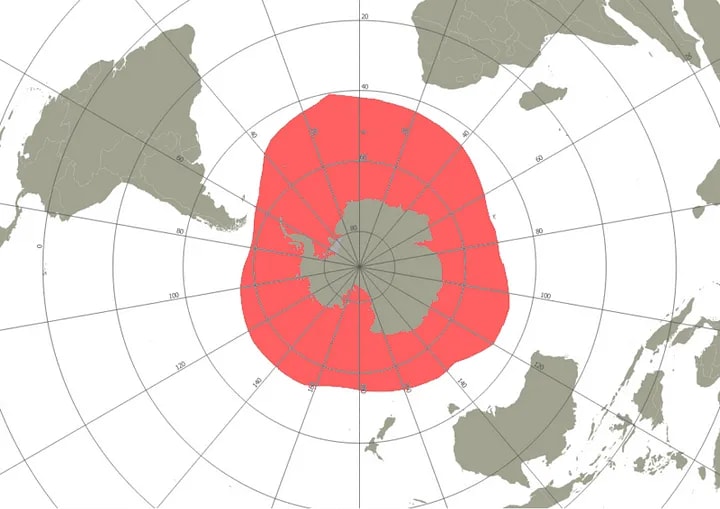

The Route

The current Vendee Globe Route is substantially the same as the Golden Globe although there are a couple of required routing waypoints and ice exclusion zones around Antarctica in the current races.

The challenge of qualifying to enter

One of the first Golden Globe competitors, Donald Crowhurst, had only ever done day sailing and he ended up faking details of his voyage and then committing suicide after a mental breakdown during the race.

Today’s Vendee Globe is much more demanding about entry requirements. The competitors are elite sailors.

And they require elite boats. These conform to a basic class rule, IMOCA 60, much like classes in motorsport such as the F1 rule.

The Imoca 60 class is the most advanced single-handed sailing yacht class in the world. Hi-tech construction, bleeding edge electronics and sail systems, but even older boats are still competitive. That's because so much depends on the weather and the sailor.

Surely these 18 m (60 feet) long, high-tech foiling vessels capable of over 30 knots and typically costing over five million euros are the F1 cars of sailing?

On top of that a shore-support team has to be funded.

So, if you can get the sponsorship or have a rich daddy then off you go.

But not quite.

The race is physically tough, mentally tough and breaks boats and people.

To mitigate the risks, competitors are required to undergo medical and survival courses. They must also be able to demonstrate prior racing experience; either a completed single-handed trans-oceanic race or the completion of a previous Vendée Globe. The qualifying race must have been completed on the same boat as the one the sailor will race in the Vendée Globe; or the competitor must complete an additional trans-oceanic observation passage, of not less than 2,500 miles (4,000 km), at an average speed of at least 7 knots (13 km/h), with his or her boat. — Wikipedia

So, you got to the start. What next?

24,000 nautical miles, three Great Capes. Hell at sea.

Once the race begins at Les Sables d’Olonne in Brittany, France, competitors you face a constant barrage of challenges. Not least is just getting out of the Bay of Biscay if the weather is bad. It's a notorious area.

There will be battles with hurricane-force winds, monstrous seas and often freezing temperatures as you attempt to keep your boat moving forward day after day, week after week. You cannot seek shelter if you are to have any chance of winning. Outside assistance (other than by radio) is not permitted by the rules.

There are warm sunny days too, perfect sailing days. And hellishly frustrating days with little or no wind.

And there you are, 24 hours a day trying to keep the yacht sailing at its full potential. No engine.

Things break and have to be fixed. You can never get enough sleep. In the southern ocean you need to consume more than 6000 calories a day. Hot food from a single burner stove.

Shit in a bucket while riding a bronco.

You have an autopilot and back up, satellite navigation all the modern technology (well, except the bucket).

You have radio/satphone contact with your weather routing people to tell you where the bad weather is and how to avoid it.

But there’s a balance — the stronger winds help you sail faster but there’s more risk.

Where’s the optimum route to keep the boat sailing flat-out without breaking you or the boat?

People to pick your morale up when it's rock bottom, advise you on treating injuries - to you and the boat. All by radio/satphone.

But it’s all down to you. How much can you take?

And then you need to record and transmit videos back to your race HQ to keep your sponsors happy. Smiling in hell. You’re floating in their boat, right?

The Three Great Capes

The Three Great Capes to be rounded in the race are the Cape of Good Hope (South Africa), Cape Leeuwin (Western Australia) and Cape Horn (South America).

There are no rest stops or pit crews to rely on, and breakdowns or injuries can often prove fatal in such isolated conditions. This makes the Vendee Globe an incredibly tough and dangerous race, and one that few people would even consider taking on.

Alone, up to a thousand miles from anywhere.

The Southern Ocean is a killer. The Roaring Forties, The Furious Fifties and if things go badly, The Screaming Sixties.

The dangers of the Southern Ocean…

…and the Legion d’Honneur medal for bravery in the Southern Ocean

The mental and physical challenges that competitors face are unlike anything else in the world of sport, and it takes a special kind of person to even make it to the start line, let alone complete the race.

So, is the Vendee Globe the world’s toughest sports event?

I believe that it is.

Not even climbing Everest can compare.

And there’s still time to enter if you’re up for it.

No stops.

And me? I’m now at anchor just north of the Southern Ocean right now, in the Antipodes, and contemplating another slow 1,200 mile solo passage to warmer climes in the next few weeks.

I’m hoping for good weather — and I’ll be taking ice in my rum.

Note that this yacht in the video can sail faster than the French frigate at top speed. Single handed.

Update: A storm hit us in our 1,200 mile crossing of the Tasman Sea from New Zealand to Australia. 2 sails were blown out. I'm still writing.

***

Canonical link: This story was first published on Medium [edited]

About the Creator

James Marinero

I live on a boat and write as I sail slowly around the world. Follow me for a varied story diet: true stories, humor, tech, AI, travel, geopolitics and more. I also write techno thrillers, with six to my name. More of my stories on Medium

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.