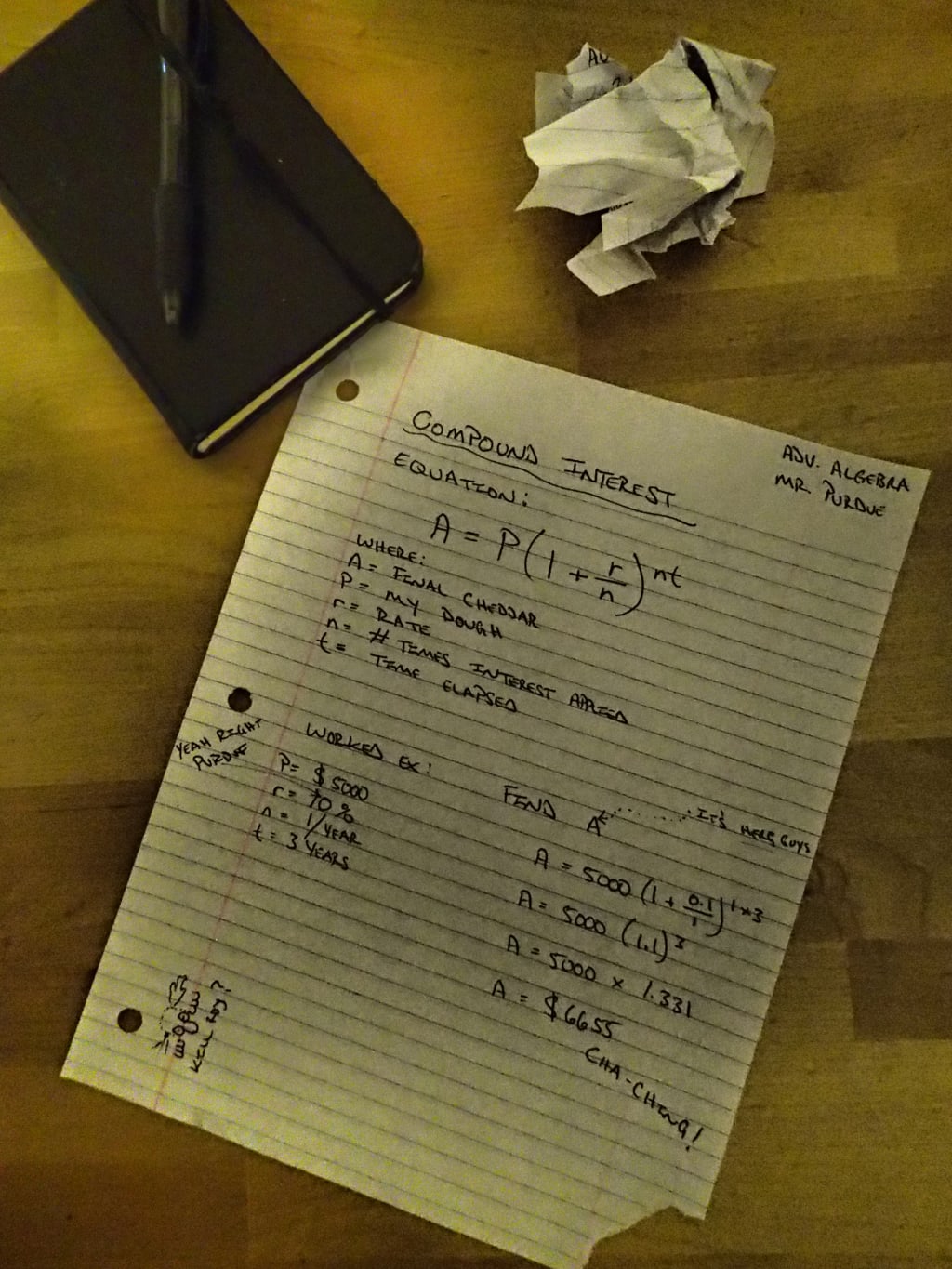

“The total amount, A, equals the principal, P, multiplied by the summation of one plus… where n is the number of times interest is compounded…” I feigned Herculean effort and grunted like I had just successfully squatted mom’s minivan. Mr. Purdue’s Advanced Algebra was my final labor. Pass the exam, and summer was mine.

And so I did and so it was.

On the eve of my sixteenth birthday - I was a June baby - my mother informed me of the next mile marker on my route to manhood. She relinquished not a moment of fantastical reprieve: I was to open a savings account.

I reminded my mother I had no money. She riposted most keenly; Grandpa always wrote a one-hundred dollar check as my birthday gift. Fate dealt the final blow: the town’s sole financial establishment required a precisely equivalent minimum opening deposit. Goodbye new video game. Goodbye amusement park entrance fee. Goodbye, even to you, double-scoop ice cream cone. Adulthood, in a word, sucked.

Melancholic apathy overtook me on the road to the bank.

“Mom,” I said, “what’s the point?”

“It’s for your future,” she deigned to descend into platitudes. “You’ll want to retire one day.”

“I haven’t even started working! Isn’t the goal in life to do what you love? To find the job that never feels like a day of work?”

Her silence was answer enough. It was a Pyrrhic victory anyway. I might as well have flushed the check down the toilet. It had just as much purchasing power parity that way.

The teller was cuter than I imagined. She offered me a lollipop. Clearly, the attraction was a-mutual. She forwarded us to her opposite - in every conceivable application of the term - number. His name was Bob and he liked my shirt. I assumed his was a lame attempt at irony, but I was too busy unraveling the mystery flavor of my lolly to humor the oaf.

He engaged my mother in the parlance of banking. I felt like a third wheel in this affair. Gross. He dove into his cheap suit jacket and produced a little black notebook. Bob turned it over in his hands unconsciously like it was a brass heirloom Zippo from the shores of Iwo Jima. He flopped down the notebook in front of me and flipped to a blank page. I suspected they were all blank.

“Go ahead, son,” he cajoled me with the finesse of a rodeo clown, “write down a figure. Fancy yourself in a sports car?”

Bob was a bland-ish man; his blandishments served him appropriately. Pen in hand, I paused. I considered an unrecognizable number, say, 𝑖. It was fitting: returns on savings accounts lingered around the imaginary. A matronly prod forced my hand. I scribbled 20,000 with reckless abandon. That’s how a sports car would end up, if in my hands. Wrecked and abandoned.

“A good round number, kid.”

I asked him if he, too, had learned his math with Purdue. He hitched a thumb over his shoulder. A Ball State paper-type of completionist trophy hung lollingly on the wall. Irrefutable proof that college wasn’t for everyone.

“Now for the magic!” Bob eeked out a few robot noises as he typed the data into his computer. It took a magician like Bob to screw up that metaphor. “Drumroll please, Mom.”

Drumrolls are meant to build tension. That’s why they were an integral part of the French Revolution. My mother executed hers. But it was I who lost my head.

“In 40 years time, you will more than exceed your sports car goal! Just in time for that late mid-life crisis,” Bob chuckled. “Just don’t forget to keep making your contributions. Pretty sweet, right? Money for nothin’.”

On the ride home, Mom asked me why I was so woebegone. I sidestepped passive aggressively. “Isn’t it interesting that decimal and decimate share a Latin root?”

I didn’t return to the depositorium for a year. I took a minimum wage, minimum effort job at the local donation center for a nationwide secondhand chain. Bob and banking tandemly taught me to rely on nobody.

By the next birthday, I had come to recognize the burden of cashing every check. Meager as their sum total was, I wasn’t comfortable with a billfold eternally struggling in mid-quack. Plus, the bank requested a cessation of my walk-throughs of their drive-thru. I would have to conduct business within the premises.

A copycat tintinnabulation erupted electronically upon my entrance. The tellers’ counter lacked any emasculating lolly-donating young women - or men, for that matter. This type of quietude was normally reserved for a stick-up’s preamble. Bob came barreling out of the back room.

“Hey, champ! What can I do you for?”

“I would like to make a deposit.” I wouldn’t like to, but it saved time to say so. Any explanation involving early-onset wallet neuritis, I was confident, would breach banker-bankee impersonality.

I stepped into Bob’s cubically-bounded area he referred to as his office. I surmised he wished me not to sit. I had come straight from work and smelled like grandma’s favorite nighty posthumously discovered in a box of vinyls behind the old console television; some days at work blurred the line between donation center and town landfill. I sat anyway.

“Ok,” Bob began after disarming me of my identity, “let’s take a look at your account’s progress.”

I had had a teacher in middle school apply the catchphrase “silence is golden, so let’s get rich” in lieu of the lewdly effective “shut yer traps”. This was the first time I really penetrated the meaning of the phrase. Eventually Bob recovered some locomotion to his mandible.

“It, hmm, well, the thing is...”

Locomotion, yes. Like a blustery steam engine.

That evening I checked my old Advanced Algebra notes. “A equals P multiplied by the summation of one plus the rate divided by n-times compounded all raised to the power of nt.” The numbers checked out. Theoretically, I was a few quarters richer than the year before.

At Bob’s behest, I returned to the bank the following day. He was caught in dire straits. His lugubriousness brought a cheer to the darkest corners of my heart.

“Gonna get that sports car then, tiger?” Bob sighed heavily.

“I think I’ll invest. I’ve heard good things about index funds,” I replied.

“Money for nothin’?”

“Clicked A for P?”

I gained no fame for my decision. I hardly told a soul. A non-disclosure agreement saw to that. The bank sought to brush over the whole incident as some sort of rounding error. Bob appreciated my principled effort to retain his job for him. As long as I kept the twenty thousand dollars in the account, they could keep the loss under wraps, as banks are wont to do.

My mother told me she was proud of the decision I made, that I was starting to act like a man. I shrugged off the compliment and explained it was merely pragmatism. The basement might flood tomorrow. I might like to go to university - loan-free - next year. A global disaster might result in mass furloughs and lay-offs in a decade. Or I might even want to retire one day.

About the Creator

Nom de Guerre

A wayward seafarer only truly found on the deep; all at sea when on land.

Creative writing is a hobby I aim to professionalize as the next step in my career quartet - soldier, sailor, writer, rogue.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.