Pink or Blue: Gender conformity in different sexes

An observational research on a small group of University students in the United Kingdom.

Abstract

Gender Identity is important for the functional progress of society, as some behaviours which belong to masculine or feminine norms can impede the progression of society, such as aggression or assertiveness. This observational research observes if gender conformity is still alive in modern society, and if subconsciously males and females tend to prefer to the colour associated with their own gender. Researchers hypothesized that there would be a significant correlation between the sex of the samples observed and whatever they would pick a blue coded or a pink coded cake. However, results show that there is no significant difference between the choices of gender-associated colour between the two groups. This might indicate that the conformity to gender norms and values are not as strong with age, or that perhaps the observational design allowed the samples to not be obstructed by the social desirability bias. Results might also suggest that individuals are not controlled by gender norms, but rather act following their free will.

Introduction

It is not uncommon to find new-born babies dressed in pink if they are females or blue if they are males. In Western societies these two colours represent the qualities that males and females should possess and are utilised as a way of distinguishing what sex the baby is. As the new-borns grow older, their parents will choose which toys to make them play with, and these toys are commonly of the same colours of their clothes when they were younger, to reinforce the connection with their gender identities (e.g. blue toy cars will be bought for boys and pink dolls will be bought for girls). Additionally, research suggests that parents are more likely to buy toys that reflect the same gender expectations of their child, or that are gender neutral, rather than buying toys that are specifically for the other gender (Kollmayer, M., Schultes, MT., Schober, B. et al., 2018) and according to J. Cunningham and C. Neil Macrae (2008) these toys are often gender-coloured.

This colour association with sex and in particularly gender was opposite before the 20th Century, as blue was considered a feminine colour deriving from Christian iconography. In Christian iconography the Virgin Mary was often portrayed as dressing in dark blue clothes, and that depiction made it conventional to associate any female to blue, as the most important female would wear blue (P. Frassanito, B. Pettorini, 2008). The modern gender associations with pink and blue perhaps come from the period of the Second World War, in which Nazi Germany identified homosexual individuals with a pink triangle in concentration camps, and this association might convey that by the 1930s pink was seen as a symbol of femininity, since homosexual individuals are often perceived as being more feminine than other heterosexual males (P. Frassanito, B. Pettorini, 2008). Although the differences between feminine and masculine qualities are clear as they are opposite (such as strong for masculinity and weak for femininity), gender roles are not always clearly defined, but can change throughout life, diverse individuals and cultures (Fausto-Sterling, 2000; Harris, 1994; Spence, 1993).

Research show that colour cues for pink and blue are associated to feminine or masculine characteristics, as pictures of men and women wearing pink clothing were identified to possess feminine personality traits (such as being affectionate) and vice-versa, that is men and women wearing blue were portrayed as having a masculine personality (such as being independent) which J. Cunningham and C. Neil Macrae (2008) relate to the possible strong color cues associations that children receive when they are infants, dressing and playing with blue or pink coloured objects.

The identification with a feminine or a masculine gender can be of essential importance in society, as a strong connection with toxic masculinity (which is the exaggeration of the most damaging masculine characteristics and the forceful separation from any emotion that is not anger), was linked by A. Oakley, (1972) as she believed that there is a very thin line between what is masculine and what is criminal. This observational research was inspired by these studies on the connection between gender and colours, especially on the gender associations for feminine with pink, and masculine with blue, which was represented by a cupcake holder of the colour blue or pink.

The researcher witnessed whatever random subjects would pick a free blue or pink cupcake, and if they belonged to females or males. It was predicted that females would pick the pink cupcake holder more than the blue cupcake holder, in consonance with a previous cross-cultural study which suggests that young women have the tendency to prefer reddish-purple colours, while young men have the tendency to prefer blue-greenish colours when asked to quickly select which colour would be their favourite from a given range of different hues and colours (Hurlbert, A. C., & Ling, Y, 2007) which was linked to be a result of evolutionary instincts that are still present in the brain, such as females trying to find red consumable leaves which evolved in making choices that are conforming in their roles of care-givers and empathisers.

Moreover, the hypothesis was congruent with a longitudinal study concerning children aged from 7 months to 5 years, which suggests that boys and girls initially prefer blue, but boys with age start to grow a feeling of avoidance towards pink, therefore always preferring blue if having to choose between the two colours (LoBue, V., & DeLoache, J. S. 2011).

Method

Design

This study was an observational study; hence the researchers did not manipulate the variables. In order to prevent any kind of overt or hidden biases, the researchers simply observed which colour the males or female voluntary subjects chose. The predictor variable was the colour of the cupcake (pink or blue) and The possible outcomes were four: males who choose a cupcake with a pink cupcake holder, males who choose a cupcake with a blue cupcake holder, females who choose a cupcake with a pink cupcake holder and females who choose a cupcake with a blue cupcake holder. The variable Female was distinguished by the score “1” because the letter “F” appears before the letter M in the alphabet, and the variable Male was distinguished by the score “2” for the opposite reason.

Participants

The total of participants was 60, which included 28 female participants and 32 male participants. All the participants were collected in England.

Procedure

A team of 7 undergraduate students collected the data by leaving 10 cupcakes each in a public space, of which 5 had a pink cupcake holder and 5 had a blue cupcake holder. The researchers noted if a male or female participant collected a blue or pink cupcake. After all the cupcakes were collected, the scores were summed.

Measures

The researchers prepared 60 simple cupcakes, then used premade pink or blue cupcake holders. In order to analyse the data, it was used the program SPSS, and in order to calculate the significance of the observational study the Chi-Squared test was used.

Ethical Considerations

Debriefing was respected as after the samples made the choice of selecting either the cupcake associated with pink or the cupcake associated with blue, we debriefed them by explaining the aim of the observational study they took part in and thanked them. There was no risk of psychological harm as the cupcakes were offered for free and had to be picked voluntarily. In case the subjects had any allergies, the researchers specified the ingredients and that the cupcakes were not gluten free to prevent physical harm. Confidentiality was respected as the subjects’ names were not noted, but only their choices and sex, so that it would be impossible to know whose behaviour was recorded. The data was shared between student emails and ultimately on the Moodle page of the University, which is protected by password.

Results

The data was summarised by summing all the scores for each outcome, thus counting for an example how many male samples made the choice of picking the pink coded cupcakes, how many female samples choose the pink coded cupcakes, how many male samples picked the blue coded cupcakes and how many female samples picked the blue coded cupcakes. To analyse the data on the program SPSS, a chi squared test was utilised, since both variables were nominal. In the total of 60 participants, 12 females picked blue and 16 pink, while 20 males picked blue and 12 males picked pink.

The results were related in a condition of non-significance and women did not prefer pink nor men preferred blue, neither the contrary, X^₂ (1,60)= 2.32,p=.13. Furthermore, the odds ratio showed males and females were only 2.22 times as likely to choose their gender assigned colour.

Table 1- A cross table with the frequency of the results

Female Male Total

Pink Count 16 12 28

Expected count 14.9 13.1 28.0

Blue Count 12 20 32

Expected count 17.1 14.9 32.0

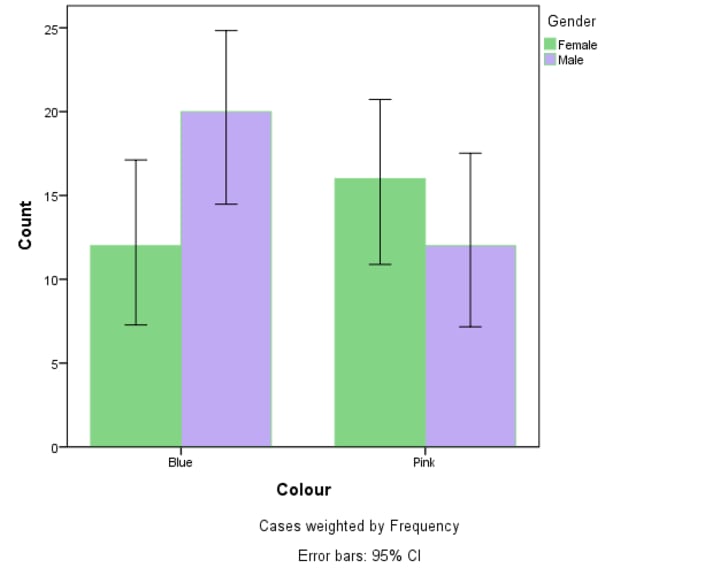

Figure 2, a bar chart showing mean count for the four variables

Although the total count for females picking pink cupcake sleeves was higher than the total count for females picking blue cupcake sleeves, just as the total count for males picking blue cupcake sleeves was higher than the total count for males picking pink cupcake sleeves, the confidence intervals shown in the bar chart (Figure 2) show that there was no real difference between the choices of the samples, as the 95% confidence intervals overlap 95% CI=(0.79, 6.25) and the P- value was found to be non-significant. On the x axis it was represented the Colour chosen and on the y axis it was represented the total count of colour coded cupcake chosen. These results suggest that it will be unlikely for the target population of male and females to conform to their gender expectations and prefer pink other than blue or the contrary. In consequence of the results gathered, Hypothesis 1 was rejected.

Discussion

From the results gathered, there is no preference for pink or blue for males or females. The hypothesis that females would prefer pink and males would prefer blue was rejected as it was found no significance between the two variables. The results contradict the research carried out by Hurbert, A.C. & Ling, Y. (2007), perhaps because the current research was based on an observation and not on an experimental study, which means that the samples were not aware of the researchers recording their choices, contrarily to the participants of the study of Hurbert, A.C. & Ling, Y. (2007), which might have modified their behaviour towards conforming to social norms, in order to pursue social desirability towards their own gender expectations. This was supported by a study conducted by Fisher, R., Dubé, L., et al (2005), which indicates if asked in a social environment, males and females will have different levels of emotional responses (males will show less emotions than females) while watching a moving advertisement. If asked privately, there will be no significant difference between the responses of males and females (Fisher, R., Dubé, L., et al, 2005).

The results gathered are in contradiction with the findings of the longitudinal study carried out by LoBue, V., & DeLoache, J. S. (2011), as it suggests that while boys learn to avoid pink, and girls start to develop an affinity for the colour pink from the age of 2 and a half years old. The current study is although congruent with the longitudinal findings of the study, as LoBue, V., & DeLoache, J. S. (2011) argue that this affinity moderately fades when the girls reach the age of 5. Research from a longitudinal study by Trautner et al. (2005) suggests children are more convinced of gender-stereotyped behaviour around 3 or 4 years old and less rigid around 5 or 6 years old, and it is around that age that children believe both girls and boys can be flexible in their behaviour, and not conform to their gender roles. These results might be the product of learning behaviour that girls and boys develop to be able to relate to their own gender. The difference in colour choice might not be significant anymore in our study as, in concordance to Trautner et al. (2005), the views of children are not as strict with age in relation to gender-stereotyped behaviour, but also it might be because in this century the views around gender are more expanded and do not correspond only to masculine or feminine, but there has been an increasing number of individuals who identify their self as not belonging strictly to femininity or masculinity, or as both, or as neither, or deny that gender exists and it is in fact a social construct but very limited literature on these groups (Richards, C., Bouman, W. P., Seal, L., Barker, M. J., Nieder, T. O., & T’Sjoen, G.,2016).

A study that instead could conform to the findings of this observational study is the research carried out by Jadva, V., Hines, M., & Golombok, S. (2010), in which 120 infants from 12 to 24 months preferred colours in red tones instead of colours in blue tones, arguing that girls and boys might learn to prefer respectively pink and blue, just as the long-term findings of the study by LoBue, V., & DeLoache, J. S. (2011) argues.

The current research might lack face validity because although pink and blue are usually perceived as feminine and masculine stereotyped colours, the cupcake choice might have not been done with the intention of establishing oneself as either feminine or masculine. The choice could have been accidental or done because of colour preferences. Furthermore, it might be possible that the subjects did not notice the colour of the cupcake holder, as it was in a lower position than the cupcake itself. In addition, as discussed beforehand, gender is a spectrum and can vary cross-culturally, during lifespans and in individuals (Fausto-Sterling, 2000; Harris, 1994; Spence, 1993). It would be interesting perhaps to observe the responses of individuals belonging to non-gender binary groups, and if they still unknowingly conform to their gender normative colour of the sex they were assigned at when born. It could also be useful to know the ethnicity of the subjects, because the culture in which they were educated in could perhaps impact their choice more than other factors. Lastly, it could be useful to know if the parents of the samples were rigid and educated them in a gender normative manner.

Not having found a significant difference of colour picked in males and females, this study might be significant because it could be in support of the theory of free-will. This can be because instead of following the norms and values that were thought to them as child the subjects made their own choice, uncaring of the norm. The results could also suggest that males and females who believe they are in a situation of not being observed by other individuals will choose more freely, since they believe they are not obliged to follow social norms. Young adults might have learned to unfollow gender roles with age, as most research suggests that younger children will conform to these rules. Finally, the non-significant difference might be a synonym of the more open views that the 20th and 21st century in the Western world has begun to adapt.

References

Alexander, G. M. (2003). An evolutionary perspective of sex-typed toy preferences: Pink, blue, and the brain. Archives of sexual behavior, 32(1), 7-14.

Brownlie, E. B. (2006). Young adults’ constructions of gender conformity and nonconformity: AQ methodological study. Feminism & Psychology, 16(3), 289-306

Cunningham, S. J., & Macrae, C. N. (2011). The colour of gender stereotyping. British Journal of Psychology, 102(3), 598-614.

Fausto-Sterling, A. (2000) Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of

Sexuality. New York: Basic Books.

Fisher, R. J., & Dubé, L. (2005). Gender differences in responses to emotional advertising: A social desirability perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 850-858.

Frassanito, P., & Pettorini, B. (2008). Pink and blue: the color of gender. Child's Nervous System, 24(8), 881-882.

Harris, A.C. (1994) ‘Ethnicity as A Determinant of Sex Role Identity: A Replication Study

of Item Selection for the Bem Sex Role Inventory’, Sex Roles 31(3–4): 241–73.

Hurlbert, A. C., & Ling, Y. (2007). Biological components of sex differences in color preference. Current biology, 17(16), R623-R625.

Jadva, V., Hines, M., & Golombok, S. (2010). Infants’ preferences for toys, colors, and shapes: Sex differences and similarities. Archives of sexual behavior, 39(6), 1261-1273.

Kollmayer, M., Schultes, M. T., Schober, B., Hodosi, T., & Spiel, C. (2018). Parents’ Judgments about the Desirability of Toys for Their Children: Associations with Gender Role Attitudes, Gender-typing of Toys, and Demographics. Sex Roles, 1-13.

Oakley, A. (1972). Sex, gender and society. London: Temple Smith.

Richards, C., Bouman, W. P., Seal, L., Barker, M. J., Nieder, T. O., & T’Sjoen, G. (2016). Non-binary or genderqueer genders. International Review of Psychiatry, 28(1), 95-102.

Spence, J.T. (1993) ‘Gender-Related Traits and Gender Ideology: Evidence for a

Multifactorial Theory’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64(4): 624–35.

About the Creator

Oliva Baron

Read me if you want to combine a bit of fun with a bit of research.

I love exploring ideas of Psychological advances, sexual expression, food, fashion and ecological swaps.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.