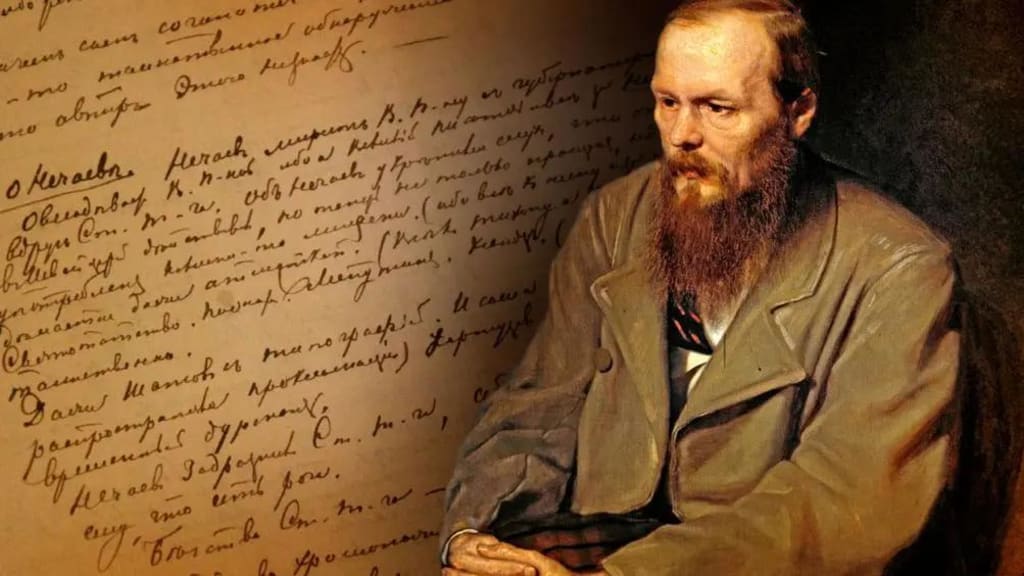

When it comes to Russian literature, the mountain that cannot be bypassed is Dostoyevsky, and the novel Swarm of Demons is one of dostoyevsky's most representative works. The story is based on the famous "Nechaev case" that happened in Moscow in 1869. Nechaev, a student of The University of Petersburg, met the anarchist Bakunin abroad. After returning to Moscow, he established the people's Punishment Society, a secret organization against the government, and set up several secret "five groups", mostly students. His despotism and authoritarianism caused so much discontent within the group that Ivanov, the model for the fictional character Satov, wanted to quit the organization. Finally, at Nechaev's instigation, the team members assassinated Ivanov out of fear of his informant.

The main plot of the novel also revolves around this real event, but it is more profound and heavy. It describes a group of absurd and painful souls wandering in the twilight zone of good and evil and wandering in nihilism after the absence of God. The most impressive are the nihilists in Dostoevsky's novels. In this article, I would like to talk about the two suicides in the novel, Kirilov and Stavrogin.

Suicide is a very important proposition in philosophy, especially in existentialist philosophy, and also a literary image that can not be ignored in many literary works at home and abroad. "There is only one really serious philosophical problem -- suicide," Said Albert Camus powerfully in the Myth of Sisyphus. There are many images of suicides in Dostoyevsky's novels, such as Smertyakov in The Brothers Karamazov, Sverigarov in Crime and Punishment, and Stavrogin and Kirilov in the demons. Ivan in The Brothers Karamazov argues: "The secret of man's existence lies not in merely living, but in why he lives. Without a firm belief in why one is alive, one is unwilling to live, committing suicide rather than remaining in the world." Undeniably, there is a sublime transcendence in such thoughts, and in some sense it is even the embodiment of man's divinity. Just as Nabokov said in his novel, "A man who decides to commit suicide is a god." Suicide can indeed be regarded as a challenge and rebellion against god. God cannot commit suicide, so people who commit suicide can do what God cannot do, which is also a reflection of the philosophical implication of suicide. But Dostoyevsky seems to think about this problem in the mutual encroachment of abyss and divinity, so his suicide has a more complex meaning.

Kirilov does not take up much space in "The Demons", but his views on suicide and the dialogue with Verkhovsky before committing suicide are very classic, he is a very prominent and typical image of suicide in Dostoyevsky's works. Kirilov was an atheist architect and a member of a secret society. But his job was to commit suicide when someone in the group did something dishonorable and the authorities pursued the culprit. Kirilov talks about his thoughts on suicide in a conversation with the novel's narrator "I". He believed that God was caused by people's fear of death, and that anyone who could overcome pain and fear could become God. "Anyone who wants maximum freedom should dare to commit suicide. Whoever dares to commit suicide will be able to see through the deception. Besides, there would be no more freedom; That's all there is to it. Whoever dares to commit suicide is a god. Now anyone can do neither God nor everything. But no one has done that, not once." Oates sees Kirilov as "an unwilling God, an unwilling victim". In kirilov's words, he committed suicide to prove his personal will beyond the collective will and to demonstrate his absolute free will. "I had to shoot myself, because the culmination of my complete, complete freedom to do whatever I wanted was suicide." In this sense, his suicide is metaphysical, just like Nietzsche's startling "God is dead", in which Kirilov seems to be shooting at his Own God and making himself a new God.

Is he really such a Nietzschean figure rebelling against God? I don't think so, or not exactly. Many of the characters of nineteenth-century Russian writers were nihilistic, walking in the wilderness of self-deception in search of inner peace. Kirilov was actually such a nihilist, and his nihilistic thoughts were most vividly expressed in his dialogue with Verkhovinsky before he committed suicide. His suicide is a kind of self-deception. As Irina Papelno puts it, Kirilov was trapped in an antinomy -- "a moral need for the existence of God and an empirical knowledge that god does not exist". He could not face the absurd world without God, but he could not believe in God. The cruel and false world needed God, so he chose to commit suicide and become God: "For me, there is no higher thought than no God... The whole history of the world is that man has contrived a God in order to live without committing suicide. I am the only one in the history of the world who, for the first time, did not wish to think of a God." He cloaks his suicide in transcendence, but ironically it actually serves the SINS of revolutionaries like Verkhovinsky whom he despises.

Chekhov, also a Russian writer, also describes a group of self-deceiving nihilists in his novels. They either maintain a fragile memory shell in the imitation game of the past, or place the future on transcendence, which is completely based on ritualized behavior, so as to complete the self-deceiving resistance to nihilism. Kirilov self-deception, he deceived based on his suicide logic, he would suicide as an act of absolute transcendence, he has seemed close to divine the suicide of logic, but with their own suicide to shield the murderer, let his eyes so great free will to fulfill a despicable evil lies, how ironic. He grasped the philosophy and divinity of suicide to completely deny everything in reality and overturn everything in reality, so as to escape from the fear brought by death and the nothingness of reality. But in fact, he made reality and self more nihilistic. Instead of becoming God, nihilism and absurdity became the new God. As Stepanovic described him, he was eaten by his own thoughts. At the same time, he continued to delay suicide in order to complete the task of the secret organization, but also turned the act of suicide into a pure ritual in his heart to fulfill his own divinity.

Writing here, I have to think about a question, can people become God? Perhaps the first thing we need to address is a topic unfamiliar to our culture: what does God look like in the context of modern philosophy? "People turn to God when they want the impossible," Shestov pointed out in The Rule of keys. Camus even pointed out that in Shestov's thought, God was actually "hateful, hateful, unreasonable and contradictory", and "The greatness of God lies in its bewilderment; The proof of God is that he is unworldly. No wonder Nietzsche cried out that God was dead and turned to the nihilistic inquiry: can man live without faith? So can man really be God? Does man become God when he loses everything to hold on to, to believe in, loses all limits, transcends all sacredness? Or will it be swallowed up in the wilderness of spiritual boundaries by an unbounded nothingness? Nor can I answer this age-old question. But perhaps the second suicide, Stavrogin, touched the edge of the problem.

Stavrogin is a completely different kind of suicide from Kirilov. Many consider him to be the real main character in "The Demons," and Bergayev even argues that the other characters in "The Demons" are merely vehicles for Dostoyevsky's ideas, "whereas [he] knows Stavrogin as well as evil and destruction." In the novel, Stavrogin seems to be a complete nihilist, deconstructing all notions of the world, indifferent to good and evil, indifferent to love and hate, indifferent to everything and everyone in his life. He was like a desperate wanderer, beyond all conception, utterly rootless, adrift between the abyss and the gods. In the description of the novel stavrogin is a charming and handsome noble man, all people are infatuated with him, Verkhovsky regarded him as an idol, as he is god, that he is the new truth. Everyone loves him and hates him, and he seems to have become a framed god of nothingness. But he is also a figure of absolute contradiction, in whom all paradoxes seem to converge.

Of course you wouldn't say he was a good man who slept around, did all sorts of things, killed people, raped a young girl, and indirectly caused her suicide. But at the same time, you could hardly say that he was a villain. Because all his evildoings have a performability, the absurdity of the figure lies precisely in the deep rift between him and the acts he presents, in the fact that he examines his own evildoings at the same time, even quickly. As he himself said, the many humiliating, despicable, and ridiculous experiences of his life, besides arousing his anger, often produced in him an incredible pleasure: "I feel a kind of ecstasy when I steal, because I realize that I am so abject. What I like is not meanness, but I like the ecstasy that comes from the painful realization of my meanness." The performativity of his behavior separates him from his own existence and even the existence of the whole world through a deep deconstruction trench. He is always watching from the other side, but his watching is not pure indifference, but a kind of self-torture. In the confessional letter he gives to the priest in the later part of the novel, he also presents a kind of confessional performance. The priest described his account thus: "There are points in your account which are reinforced by your choice of words; You seem to admire your psychology, and cling to every detail. You want only to amaze the reader with a ruthlessness that is not in you." Unlike Rama in Diderot's Rama's Nephew, the performance of confession is actually to absolve himself of sin. Stavrogin completes an aesthetic and spiritual performance through confession, which is actually a kind of self-destructive redemption. He sought a spiritual balance by amplifying his evil.

In the description of Stavrogin, one significant detail struck me. Stavrogin describes in minute detail what he feels and sees in the moment when he rapes an underage girl, Matyosha, and guesses that she will commit suicide. He heard a fly buzzing overhead, heard a cart driving up in the yard outside his window, and heard the tailor who lived in another window of the yard humming loudly. At last he saw a tiny red spider on the leaf of a hydrangea bulb. A multitude of irrelevant, vivid details filled his senses. But it is this irrelevant detail that becomes a crack in stavrogin's character's perfect nihilistic shell. The little spider had taken root in him, along with all the details of the matter. These details became his anguish, his ghost. So much so that, many years later, he had a wonderful dream on the Greek islands, and at the end of the dream, he saw the tiny spider again: "But suddenly in the midst of that bright, dazzling light, I seemed to see a tiny, tiny dot. It gradually changed into a shape, and suddenly I clearly saw a tiny starscream. I immediately remembered that it was on the leaves of hydrangea, when the sun was setting, a bunch of slanting light into the window. It was as if something had pierced my chest..."

In the end, Stavrogin's suicide is actually a response to this detail. He has been searching for a way to heal this rift all his life, but he has no faith and has been wandering on the edge of all spirits, so he can only wander in countless crazy and absurd behaviors. In contrast to Kirilov, whose apparent suicide is noble but actually nothingness, Stavrogin's apparent suicide is surprising and even absurd. Even stavrogin himself says: "I am afraid of suicide because I am afraid of showing self-sacrifice. I know it's another deception -- the last of an endless series of deception." But his suicide touched the realm of the sublime. In the New Testament, there is a thorn that goes into the flesh, a thorn that constantly attacks people and reminds them not to get too high. Kierkegaard stroked the thorn all his life, constantly using it to awaken the pain in his mind, "with the hopeless joy of being a sufferer." So there was a thorn in Stavrogin's heart, and the spider was the thorn. The thorn turned his absurdities into spiritual penance. Therefore, he is the most absurd and nihilistic person, the devil who despises God and everything in the world, but he has become the saint closest to God.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.