The Salem Witch Trials: A Legacy of Horror

As the small town of Salem was gripped with paranoia and fear, hundreds of innocent lives were ruined in the most infamous witch trial in American history.

As Giles Corey laid in the field next to the Salem jail, the sheriff ordered yet another stone to be placed atop him. After two long days of suffering as stone after stone was added, Corey could hardly breathe through the weight crushing him. Yet he could end his suffering at any time. All he had to do was agree to stand trial to defend himself from accusations of witchcraft.

Mustering up the last strength he had, Corey finally spoke up to the sheriff torturing him.

“More weight!”

A TENSE ENVIRONMENT

To better set the scene for the infamous trials, we need to put ourselves in the shoes of a villager in 1692 Salem. It’s not hard to imagine how difficult life would have been as an early American settler, without the modern comforts that we take for granted. Massachusetts’ winters on the coast of the rough North Atlantic Ocean would have been long and cold.

In addition to the rough climate, there was a degree of suspicion between those that lived there. King William’s War with the French in Canada had sent some refugees south, many ending up in Salem. These additional mouths to feed put a strain on resources and increased the tension that already existed between rivaling families.

Looking outwards, things weren’t much better. Villagers had a fear of potential attacks by local Native American tribes, and there were rivalries between Salem and nearby towns and villages. To make matters worse, a recent smallpox epidemic had weakened or killed some of the colony, adding a healthy dose of suffering and despair.

Puritans were very devout in their religion, and there was a strong belief that not only did the devil exist, but he could interact with humans. They believed that in exchange for loyalty to the devil, one could be granted powers, thus becoming a witch that could inflict torment on others.

THE SUFFERING “VICTIMS”

In January 1692, Reverend Samuel Parris, Salem’s first ordained minister, was distressed to find his 9 year old daughter Elizabeth and his 11 year old niece Abigail Williams suffering from an unusual fit. They screamed out and thrashed about, throwing things and contorting into odd shapes. It was soon discovered that several other teenage girls in the village had all experienced similar fits.

Doctor William Griggs was called to help the suffering girls. His diagnosis: the girls were bewitched.

TURNING ON EACH OTHER

On February 29th, officials Jonathan Corwin and John Hathorne met with the girls to determine the cause of their bewitchment. The victims claimed to know exactly who the witches were that tortured them: Tituba, a Caribbean woman that was enslaved to the Parris family; Sarah Good (46 years old) a local beggar; and Sarah Osborne (age 49) another impoverished woman.

On March 1st, the three women were brought before the officials for interrogation. Good and Osborne claimed their innocence, but Tituba confessed. She told them that “The devil came to me and bid me serve him”, before warning that more witches existed, seeking to bring them harm.

Once it was believed that witches were in their midst, the accusations poured forward. More teenage girls claimed they were having fits and tormented by witches. Ann Putnam Jr., Mercy Lewis, Elizabeth Hubbard, Mary Walcott, Mary Warren, Elisabeth Proctor, Susan Sheldon and Elizabeth Booth all came forward accusing neighbors of witchcraft.

Most of the accused were individuals that didn’t necessarily fit in with the strict Puritan lifestyle, or were generally disliked. However, once the pious Martha Corey (72 years old) and Rebecca Nurse (71 years old) were accused of witchcraft, people were terrified. Both women were considered devout in their faith and pillars of the community, if they could be witches, then anyone could.

While some were incredulous of the accusations, little could be done. Speaking up for the accused could earn one an accusation of their own. In fact, Martha Corey had been outspoken in her criticism of the accusations and soon she found herself on trial.

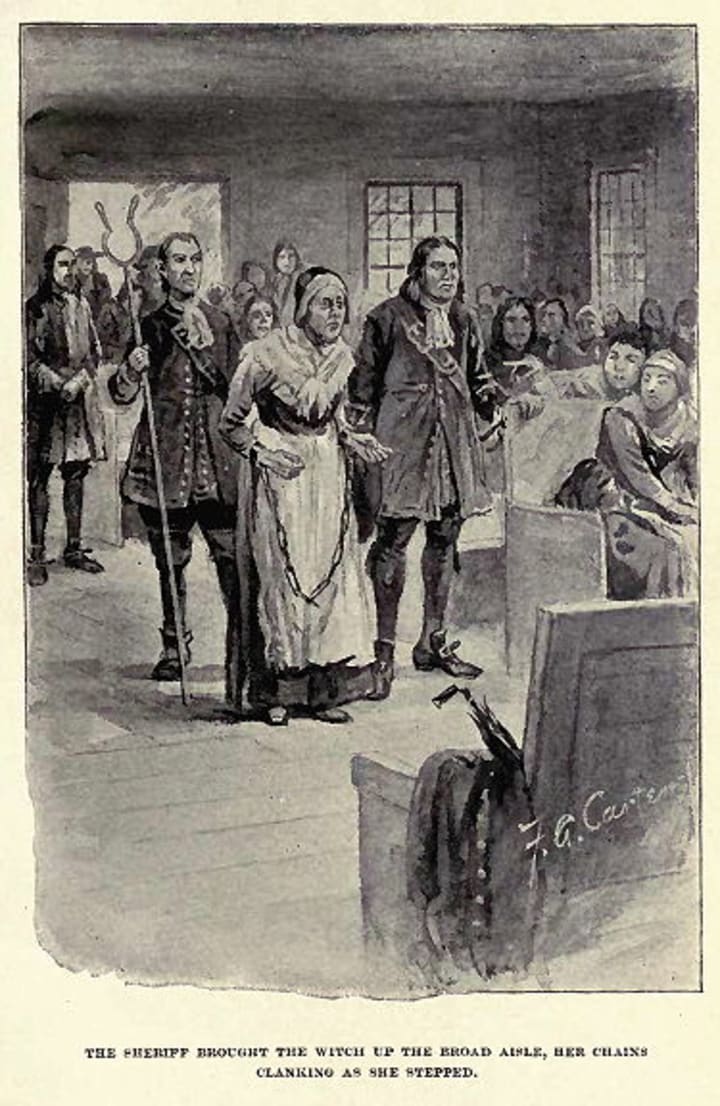

ON TRIAL

Trials were in full swing and by April, the Deputy Governor of the colony Thomas Danforth was attending the hearings. Not only were the accused questioned, but citizens from both Salem and nearby villages were asked to come in for statements. No one was safe from accusations, even 4 year old Dorothy Good, Sarah Good’s daughter, found herself imprisoned. She reportedly went insane after spending months in jail and watching her mother and sister die.

As things in Salem were getting out of hand, by the end of May, the new governor William Phips ordered a Special Court of Oyer (to hear) and Terminer (to decide), to try to settle things. Presiding over this was Chief Justice William Stoughton.

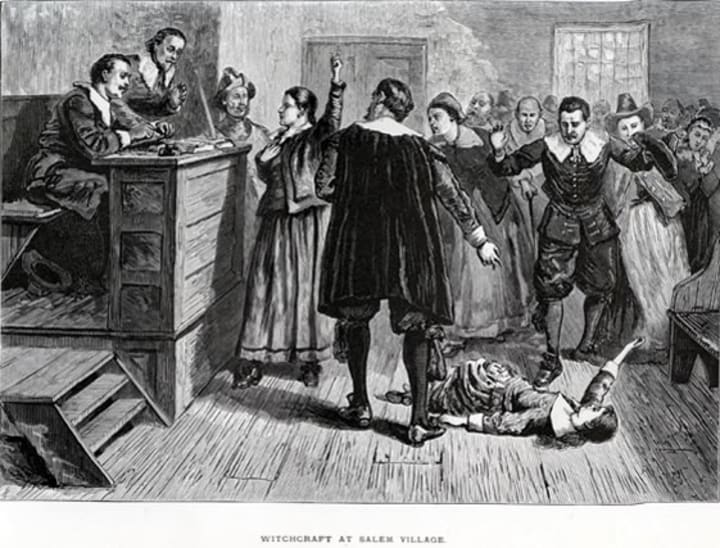

Court sessions were a dramatic scene as the accusers acted out in court. The girls screamed and cried out that the accused witch was attacking them, as onlookers watched in horror.

The minister Cotton Mather begged the court not to allow spectral evidence (testimony that the witches were torturing their victims invisibly, typically through dreams or visions) in the trials. The court ignored this request and continued.

GUILTY UNTIL PROVEN INNOCENT

It was nearly impossible for one of the accused to disprove witchcraft. The courts relied on a confession from the accused and testimony from two witnesses in addition to spectral evidence. Sometimes physical evidence such as “devil mark’s” on the witches body (typically moles or growths) would also be admitted.

An even more bizarre method of identifying a witch consisted of “witch tests”, the most famous of which was a test where the accused was tied up and dunked into water to determine if they could float. If they sank, and likely drowned, they were innocent. If they floated they were guilty and would likely be executed.

At the time, law did not assume innocent until proven guilty, and with many passages of their law taken directly from the bible, the accused hardly stood a chance.

“Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live”

EXODUS 22:18

The court promised mercy to the accused in exchange for their confessions. Even some family members of the accused begged them to confess in hopes of a lighter sentence. Of the 180 people accused, 54 of them pled guilty of witchcraft.

While perjury was considered a felony in Salem, that was largely disregarded in the hysteria. The claimant could simply continue their accusations to avoid being charged. The accused could attempt to fight back by claiming defamation, but this was wildly unsuccessful in practice as only 4 out of 15 defamation cases during the witch trials was ruled in favor of the accused witch.

THE EXECUTIONS BEGIN

The first of the accused brought to trial was 60 year old Bridget Bishop. She pleaded her case before the court claiming that she was innocent of the charges brought before her. The court disagreed and on June 10th she was the first person of the Salem Witch Trials to be hung.

As events in the town reached a fever pitch, more and more were swept up in the hysteria. In total 180 people were accused of witchcraft. 144 were jailed and 55 of these were tortured into admitting their guilt. Many spent months imprisoned and five died in jail, including Sarah Osborne (one of the first accused), and the infant daughter of Sarah Good who was born in prison.

THE REAL VICTIMS

With the hanging of Bridget Bishop on June 10, the flood gates opened and more executions followed. Between June 10th and September 22nd 1692, 20 people would be executed.

June 10, 1692

- Bridget Bishop – Age 60 – First to be formally tried and executed

July 19, 1692

- Rebecca Nurse – Age 71 – Devout churchwoman, 39 people signed a petition to defend her

- Sarah Good – Age 46 – Homeless woman and one of the first accused

- Elizabeth Howe – Age 50’s – Rebecca Nurse’s sister-in-law

- Susannah Martin – Age 70 – Impoverished woman

- Sarah Wildes – Age 65 – Prior accusations of adultery

August 19, 1692

- George Burroughs – Age 40’s – Prior minister of Salem

- George Jacobs Sr. – Age 70’s – Arrested with his granddaughter, who in turn accused him in exchange for clemency

- Martha Carrier – Age 38 – Previously had been exonerated for witchcraft accusations

- John Proctor – Age 60 – Skeptic of trials, arrested after defending his wife

- John Willard – Age 35 – Deputy constable that refused to arrest the innocent

September 19, 1692

- Giles Corey – Age 80 – Wealthy farmer and critic of the trials, husband of Martha Corey. Plead not guilty but refused to submit to a trial and was pressed to death

September 22, 1692

- Martha Corey – Age 72 – Devout churchwoman and skeptic of trials, wife of Giles Corey

- Mary Eastey – Age 58 – Rebecca Nurse’s sister and devout churchwoman

- Mary Parker – Age Unknown

- Alice Parker – Age Unknown

- Ann Pudeator – Age 70’s – Local midwife

- Wilmot Redd – Age 70’s – Mother-in-law of George Burroughs

- Margaret Scott – Age 70’s – Impoverished widow

- Samuel Wardwell Sr. – Age 49 – Renounced a prior confession he was forced to make

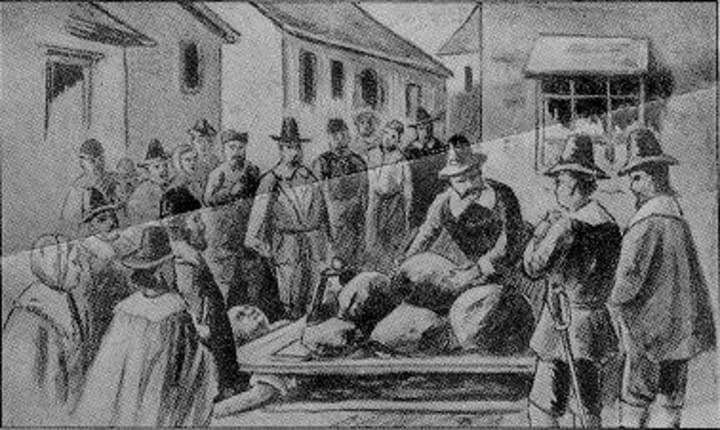

THE UNUSUAL CASE OF GILES COREY

All executed were sentenced to death by hanging, with the notable exception of Giles Corey. He plead not guilty to the accusations of witchcraft, but refused to submit to a trial as he believed that the court had already determined if he was guilty or innocent. Some sources say that the law stated that his property would be forfeited to the state if he were found guilty of witchcraft, and not to his heirs, giving him additional reason to avoid a guilty verdict.

As he refused trial, he was instead sentenced to be pressed, in which increasingly heavy weights were loaded onto the accused until they either cooperated or died. It took two long, agonizing days of torture before Corey eventually passed. Famously, his last words were “More weight”.

AN END TO HYSTERIA

After 20 executions, several dying in jail, and even the execution of two dogs that were said to be connected to the devil, the townsfolk had grown weary of the trials. In October, Governor Phips wife was accused of witchcraft and questioned, and unsurprisingly, the governor released many of the accused and ordered no further arrests.

On October 29th the Special Court of Oyer and Terminer was disbanded and Governor Phips replaced it with a Superior Court of Judicature. This court was superior indeed and did not allow spectral evidence to be admitted. The trials began to slow, and of the 56 people tried by the Superior Court, only 3 were charged. Fortunately, none were executed.

By May of 1693, all that were imprisoned for witchcraft had been pardoned by the governor, and the Salem Witch Trials had come to a close.

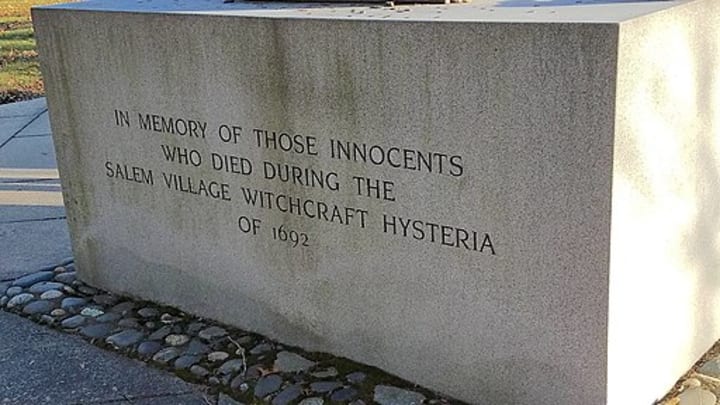

MAKING AMENDS

Over the years, the colony and state of Massachusetts’ has apologized for the trials. On January 14, 1697, the Massachusetts General Court ordered a day of “fasting and soul searching” over the tragedy. In 1702, they declared that the trials were unlawful, and in 1711 Massachusetts passed a bill restoring the rights and reputations to many of the accused. £600 in restitution was granted to the heirs of the accused.

In 1957 the state of Massachusetts formally apologized for the trials and exonerated nearly all accused of witchcraft during the trials. It wasn’t until July of 2022 that the last convicted witch, Elizabeth Johnson Jr., was officially exonerated (mostly due to a lack of heirs to petition on her behalf).

LASTING LEGACY

When all was said and done, nearly 200 people were accused of witchcraft, many of whom were imprisoned and tortured for months on end. 20 innocent people were horrifically executed and several died in prison. Lives were ruined and families torn apart due to mass hysteria and fear mongering in a once peaceful town.

Over 300 years later, we are still fascinated and horrified by the events that occurred in Salem in 1692. Perhaps it’s our innate interest in the morbid, or a fascination in historical events that seem far-fetched today. Or maybe, it’s a lingering fear of humanity’s that events like this can happen again.

RESOURCES

Blumberg, J. (2007, October 23). A Brief History of the Salem Witch Trials. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/a-brief-history-of-the-salem-witch-trials-175162489/

Dorn, N. (2022, February 8). Swimming a Witch: Evidence in 17th-century English Witchcraft Trials. Swimming a Witch: Evidence in 17th-century English Witchcraft Trials | In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress. Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2022/02/swimming-a-witch-evidence-in-17th-century-english-witchcraft-trials/

History.com Editors. (2011, November 4). Salem Witch Trials. History.com. Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/colonial-america/salem-witch-trials

McDonald, S. W. (1997, September). The Devil’s mark and the witch-prickers of Scotland. Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/014107689709000914

Purdy, E. R. (2009). Salem Witch Trials. THE FIRST AMENDMENT ENCYCLOPEDIA. Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1098/salem-witch-trials

The Salem Witch Trials Legal Resources. The University of Chicago Library. (2020, October 1). Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/collex/exhibits/salem-witch-trials-legal-resources/

Salem Witch Trials of 1692: Facts, landmarks, events, & more. Destination Salem. (2021, September 30). Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://www.salem.org/salem-witch-trials/

Salem witch trials: Accusers and accused. Research Guides – Boston Public Library. (n.d.). Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://guides.bpl.org/salemwitchtrials/accusersandaccused

Snyder, H. (2001). Giles Corey. Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://salem.lib.virginia.edu/people/gilescorey.html

About the Creator

Jen Mouzon

Sometimes truth is scarier than fiction. Obsessed with exploring and sharing myths, legends, weird history and the unexplained. Join me at hungryforlore.com.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.