The Missing Children of Akutan

Napaq Angun

The cabin in the woods had been abandoned for years, but one night, a candle burned in the window. The soft glow spilled across fresh caribou tracks along the muddy path. I’d been tracking them through the winding forest before the steps became disoriented, scattered. The caribou, they’d been spooked into the Valley of Teeth, a place beyond our borders where even the bravest among us dared not tread. In the path stood a small wooden totem of a boy with a carved hawk perched on the boy’s shoulder. The candle in the window flickered and I knew what it meant; we all did. Another child had gone missing, and it was only a matter of time before the tribal elders came to me for help. I’d been the only one to ever escape the napaq angun, the Wooden Men.

The boy with the hawk, it was my son. The napaq angun had returned to finish the job.

My birthright is Akutan, Alaska, a tribal village of nearly seven hundred inhabitants amidst the Aleutian Islands. The Akutan volcano slumbers through a restless sleep creating geysers and hot springs that steam the forest with mist. She shakes the earth during nightmares. The forests are dense with evergreen trees that claw the sky, strong of root and bark like the people who live among them, below them, with them. In Atukan, we fish. We hunt. We keep watch over the natural order when outsiders threaten to pillage our world.

My mother spoke Alutiiq when she was mad at my father, a white man, so I learned our sacred tongue in fits of passion and anger. My mixed race made me an outsider to my own community, a plugta irneq, a dog son. Any woman who bred with an outsider was considered a mongrel, though as the years passed, I wondered how much of a say my mother had in my conception. My father had been a logger with an American company that chewed through the forests of the outer lands. They took our holy lumber and shipped it to the States to build second and third homes for wealthier white people.

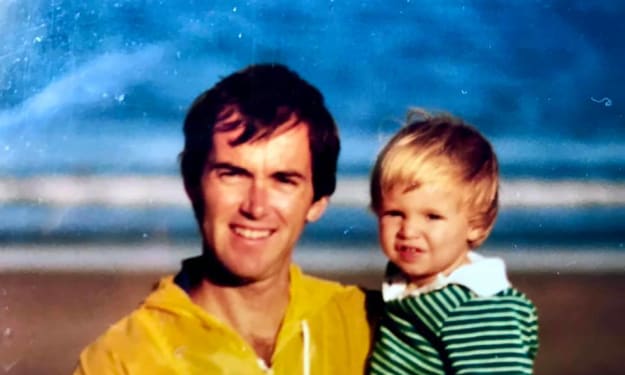

The memories of my father are few, namely that he was insistent I learn English and be given the white man’s name of Eli. Gone before I turned six, he often loaded me into a canoe and paddled into the Pacific toward foggy, uninhabited islands for camp.

“There are no laws but nature,” he told me over bonfires. The flames pushed around his thick beard and bushy eyebrows creating shadows more monster than human. “We’re animals that hunger for everything we cannot have.”

We’d sit and listen to the night. The gentle splash of waves on the rocky shore, the hawk’s cry as it sought salmon, the exploding scent of fresh pine, the odd growls rising from a valley that made my skin shriek with cold.

“What is it?” I would ask. I wanted comfort but my father was a man of unending darkness.

“Wooden Men,” he said, stoking the fire and loading the shotgun in his lap. Cocking the chamber sounded like the antler clash of warring moose. “Takers of children.”

Upon our return, my sweet mother cursed him with tribal incantations and ground spirit-herbs into his drinks as punishment for not communicating our whereabouts. She hugged and kissed me, prepared tea and fish, pushed my bed near the fireplace for me to recover from the journey while my father paced outside. His shadow beneath the moon loomed large over our home, a volcano of our own.

What I remember most about those days is the perfect pitch black of my mother’s straight hair. It reflected, captured, and hid the light, a perfect trinity for Aleutian women unmatched by others in our indigenous village.

The first child to go missing was Lukaa, a nasty boy left with half a right hand from a grizzly attack. First the grizzly, then one day he wandered into the woods and never returned. He was thirteen. At night, we heard him crying for help from all directions, a cruel mountain trick of sound and space and ice and trees. The hunters spread the message by placing a single burning candle in the window of their cabins.

In the days after his disappearance, I felt a sense of relief. Lukaa threw rocks, beat me with sticks, called my mother horrible names in front of his snickering friends. The one time I fought back, he held me down and shoved his half-hand into my mouth until I gagged and vomited.

“What’s the matter, plugta?” he laughed, his black hair braided over both shoulders. “Have you lost your appetite?”

Even his father laughed, a man of new wealth after agreeing to work with the Americans on a logging campaign beyond the Valley of Teeth. The whole family bragged about leaving Akutan, though the elders warned of turning one’s back on their people.

Lukaa was never found, though a hunting party called an emergency town meeting when they discovered a crudely carved wooden totem of a boy, hair braided over both shoulders, missing part of his hand. The elders told us that Lukaa wandered too far and was snatched by the napaq angun. His family left shortly thereafter, and their house remained empty, eventually reclaimed by the trees his father agreed to cut.

The second to go missing was a girl I’d fallen hopelessly in love with, Miko, with emerald eyes and a small nose. I’d been wanting to bring her salmon and wildflowers, but one day she left for the river and never came home. I cried for days. Some nights, I swore I saw her beyond the window beckoning me into the woods. She stood swaying with the Sitka trees at the edge of our land, though her face had sprouted leaves. Twigs grew like broken fingers from her chest. In my grief, I nearly ventured to her had it not been for the nightmarish sight of a face like tree bark and terrible, dark, soulless eyes.

She, too, only returned in the form of a found wooden totem, eyes made green from mold and decay. Each spring the color returned, and every year on the anniversary of her disappearance, the color vanished.

Devastated, her parents signed away huge plots of land to the government. The excavation, they believed, would finally bring answers.

Still, they wait.

A few seasons later, my mother caught an illness. She withered and shrunk. Her black hair lost its brilliance. Refusing to seek help, she stayed inside while I fished, hunted, and tended to home repairs. I had stepped fully into my father’s shoes. The shaman conversed with the spirits and promised recovery, but my mother denied them. I was heartbroken. Maybe she was, too. Some nights, I’d wander off the paths hoping to stumble across a hungry grizzly to chop me down in one massive blow, or a pack of starving wolves migrating with the caribou and elk, ravenous for a meal. Anything to ease the pain.

Then, one night, I awoke to the sound of my father’s voice caught on the wind.

“Eli,” it whispered. “Come to me.”

From my bed, I gazed into the darkness. Faces appeared in the trees, their cheeks cut and folded with bark, eyebrows and beard bushy with undergrowth. The ground trembled. The Akutan volcano was restless. Our small village was shrinking in population, the natural world no longer willing to support our humble tribe.

I pushed the warm cover from my bed and rose. The wind howled. The faraway rumble of diesel engines harvesting trees echoed like battle-born Kodiak. My mother slept by the dying fire. Orange embers crumbled from the log and sprayed ash up the flue. She coughed and turned. I could take no more.

The door pulled open and I stepped into the darkness with a fishing hook in my hand. I wandered into the trees and sliced my palm. Blood spilled to attract the beasts. My father’s voice said, “Yes, Eli, closer.” I smelled the thick musk of unwashed creatures before a hand slapped over my eyes and mouth, and a burlap sack swallowed me whole. In the next moment my feet were above my head and I was being carried fast through the writhing forest by something powerful, something hungry for everything it cannot have. Something inside me submitted, and I accepted the fate of being taken.

They carried me for hours, the grunts and sounds of the napaq angun my only company. I picked at the slit in my palm, the trail of blood merging with the earth. At one point we stopped and a strong hand reached into the sack, poured whiskey like my father used to drink on the wound, and laughed when I cried out in pain.

They made camp. I smelled the pit fire and heard their heaving breath while they slept. Still upside down in the dark, I only imagined wooden bodies, gnarled faces, and crooked fingers.

Before dawn I managed to turn myself upright but still I struggled to reclaim my bearings. The sounds stopped and I could not hear the wooden men stirring. Something else approached, something curious and formidable. With the force of a mountain wind the bottom of the sack tore open and I spilled to the earth, disoriented by the new light of dawn. A female grizzly shuffled back and nearly stumbled into the snuffed fire. It grunted once in warning, saw my hand, and sniffed. It huffed a warning growl but took off into the woods without incident. Somehow I had managed to convey that I was not easy food. By the edge of the fire sat a wooden totem with a hand sliced open. I picked it up. It looked like me, and so I stowed it in my pocket.

I was in the Valley of Teeth. Dead, bare trees held fast to the soil. Dried riverbeds coughed themselves to dust. Thin animals sniffed the small greens. The Akutan volcano breathed fire to the west.

And so I ran.

To the woods with trees clawing my face, away from the valley, thorny bushes snaring my legs and mud sucking at my ankles. I didn’t stop. Night fell. In the distance came a flickering light, a single candle in the window of an abandoned cabin. Lukaa’s cabin. They were looking for me, and I was close. By dawn I stumbled into the center of Akutan as a funeral procession began. My poor mother.

She had used my disappearance as her final rite.

The elders and shaman bowed upon my arrival. The spirits had blessed me with safe return. They took my mother’s ashes after releasing her soul and rubbed them into my wound. She’d be with me forever, and the tattoo glistened with the same black as her hair. From that day forward, no one dared call me plugta irneq again. Instead, they called me u-na agiitaadax – the brave friend.

The village rallied around their half-blood native and made sure to keep me well. On nights where sleep came with a heaviness of heart, the town answered my wails and brought me to the center of our village. We cleansed ourselves through throat singing and offerings. The seeds of healing took root and the shadows in the forest kept at bay.

Our village slowly rose around us again. The losses stopped, and the American loggers moved to new forests far from our borders. Still, when the night was quiet, we could hear the roar of their machinery against the land. My father’s voice still caught on the wind and as the years passed, my body filled his frame. Strong shoulders and chest, sharp eyes, and sturdy bones.

The totems sat on my windowsill in the kitchen. Long light or long night, they served as my reminder to be vigilant. What blossomed once will blossom again, even in the dark. When anyone, tribal or outsider, pushed the boundaries of the forest, the forest pushed back as a reminder that we were foolish creatures with silly ideas of hierarchy.

On the anniversary of my mother’s death, the town gathered to tell stories by the fire. We sang and danced, stomping our feet into the earth so hard that the Akutan volcano rumbled in response. At the edge of the firelight, something paced the darkness.

That was the same night that Miko’s cousin, a beautiful woman named Keilani with ice blue eyes, brought me salmon and wild flowers. Both tormented by grief, we found comfort in each other’s emptiness. I tried to avoid the lurking forest waking, the eyes I could feel on my back, my spirit. I buried myself in our shared bed but could never feel accept that we, that any of us, were alone.

⇔

Having traveled to California to study environmental law, Keilani worked out a deal with the Alaskan government to reclaim the rights to lands sold off to foresters by her family, and, once successful, became protected institutions. More new trees flourished; more new paths emerged.

We had a son. We named him Ben. On the day of his birth, hawks circled above announcing the arrival of our most sacred treasure. We believed it to be a good omen.

My wife only spoke in English, and my Alutiiq had all but faded. It was a new life, a new world blossoming in the image of the old one. We hiked paths that circled our land, hunted elk through the white birch and pine, giving silent prayer to the fallen and staying clear of the forests that hid shadows. Secretly, part of me wondered about the past and why it had not cycled back. So I kept my son distant from that place, no need to tempt free the hibernating ills of a long past chapter.

Ben learned to train hawks from the tribal elders. They whistled and the mighty birds swooped across the surface of the river to snatch salmon and bring them to us. Another whistle and the birds perched on the hide-skin gloves covering their arms.

Since the loggers had left, the salmon returned fuller and richer, their shimmering pink scales clogging the shoals.

“Adax,” Ben asked one night, “why do you keep those wooden children on the sill?” He had grown smart and clever, his eye for detail coming from his brilliant mother. I looked at him through the fading glow of the fireplace and thought of my own father.

“They serve as a reminder,” I whispered. He asked of what but I sat watching the fading light unable to put into words what it meant to be unwanted.

A few days later, Americans showed up in Akutan wishing to speak with the elders and tribal leaders. The leaders asked me to serve as council. The men with round bellies and suits soft from a life without wilderness spoke with flashing teeth and easy laughter. They promised the moon if we considered selling off part of our land again.

“Trees,” they said over and over. “An abundance of wealth greater than a forest.”

I shook my head no, and the tribal leaders ceased negotiations.

“Salmon?” one of them asked on the way out of our town hall. He looked at the bustling river. My son whistled and his hawk swooped in to twist our dinner out of the waters.

A few days later, more American men arrived on boats with large nets. Keilani alerted the government who sent in the national guard to keep them at bay. The same businessmen returned to negotiate a new deal. One of them held a handkerchief to his crushed, bleeding nose.

“We won’t take all the fish, only some of the fish,” they said. “And we need to carve better routes. The forest is dangerous passage.”

The answer remained no. Their promises meant nothing. Our village was in a rare season of prosperity and though we shared the bounty with neighboring towns, these men would never be our neighbors regardless of their place on this earth.

One of the businessmen smiled through his anger as he offered false apologies for wasting our time.

It dawned on me then who the Wooden Men were, and I felt a rising anger for not putting it together sooner. My father had never brought me to the islands to instill his dogmas in me. He had brought me there for protection, to stay away from the dark ideas that allowed these men to get whatever they wanted. He had been protecting me from the Wooden Men. But they were not the only presence in these woods. The white man was only as great as his machine. What snatched those children, what had snatched me, was more ancient and powerful than the white man could ever be.

When they left, I knew it would not be the last of their visits.

Ben and I packed for a weeklong caribou hunt days later, a necessity to replenish our red meat supply.

“Dark forces linger beyond the trees,” Keilani said, all but begging me not to go. The white birch had been cracking in the wind, the tall pines bleeding needles as red as clay. I looked at the tattoo on my palm. My mother knew how to handle darkness, and through her passing, I, too, learned to keep at bay the shadows within, and without.

“I shall cleanse them,” I said.

Two days into the hunt, Ben and I separated. I knew we shouldn’t have, but he was grown and a far better tracker than I. Still, something in me clenched. The forest had awoken. The caribou tracks appeared spooked, scattered, and so I looked toward the Valley of Teeth. There, I found the totem of my boy and the single candle burning in the window of a dilapidated cabin. I journeyed back Akutan with my blood like a volcano.

The elders asked me to face down the demons of the forest, to go retrieve what was not theirs to take, and I agreed without hesitating. Keilani cried for Ben, and so I promised to return him home to Akutan if it meant perishing in the process. My words did little to calm her anxious mind and heart.

“He’s in the Valley of Teeth,” I said. “Our blood tells me so.”

Blessed with herbs and ritual, the shaman sent me forth to retrieve Ben and free our land from this wicked curse of missing children. The napaq angun could hide no more.

Over four day’s, I traversed the paths into the vast, wide-open valley. I slept under starless skies. I shouted Ben’s name, but not even an echo returned. The unceasing terrain dipped and fell with earth, with secrets, with caves that opened like hungry mouths. I rationed my food, huddled warm by small fires, and chewed berries for energy. My mind gave dreams of isolation, of death and decay, of starvation. One night I thought I heard Ben beside me. Amongst a dreamless slumber, he said, “Adax, you are too old and slow. I am better on my own.”

Still, I pushed forward.

When the trees let up and the dry soil blew like the winds of death, I knew I was close. In due time, I came across a settlement of long trailers circling a polluted stream. Each buzzed with generators and lightbulbs, manufactured electricity to keep alive the monsters within.

One of the trailers said BAR, and so I walked up the short steps and pushed the door open. The inside smelled of fiery whiskey, sticky booze and sweat, a low light illuminating three tired and dirty men hunched over tables. Behind the bar stood a man with only half a hand, his feet chained to a long pipe. Dark braids fell over both shoulders. A woman holding a tray approached the bar and froze when she saw me, her green eyes growing large, small nose flaring in shock.

“Impossible,” Lukaa whispered.

“Where is he?” I asked. Miko pointed to a back room. The other patrons took notice of my presence and stood.

“You’re not welcome here,” one of them said. He had a round gut and thick shoulders. A beard spilled onto his chest. He reached for a knife. I struck his eye with the point of my elbow, and he dropped. The other two men, shrunken from their labors, stood and considered me before walking out the door.

Pushing open the back closet, I found my son chained to a toilet. I bent down and pulled the chains with such ferocity that it split the pipe. I was weeping.

“We can’t leave. They’ll kill us,” he whispered. His lips were dry and chapped like the land outside. His eyes drifted unfocused.

“No,” I said. “They are cowards.”

Ben collapsed into my arms and I approached the bar.

“Your birthright is Akutan,” I said to both Lukaa and Miko. “We are going home.”

With the same violence, I broke free the pipe and freed Lukaa’s ankle chain. The skin beneath boiled raw. He limped down the steps leaning on Miko for strength.

The moment we were outside in the night, we heard the cock of a shotgun and looked up to find a barrel pointed at our heads.

“You want your boy? Sign away the land,” the man said. “No one gets hurt.”

Lukaa and Miko shrank, years of obedience chaining them to fear. I stood my ground with Ben. My son looked up at me and I watched his eyes settle at the top of the distant tree line. The forest paced. He licked his lips.

“My birthright” he whispered.

Ben whistled, soft at first, then sharp and piercing. In the distance came a great cry, and then another. He whistled a looping melody and hawks darted from the trees toward the businessman’s eyes. The gun dropped and the onlookers gasped. The hawk clawed into both sockets until there were nothing but empty, bleeding holes.

I stomped and chanted as dust kicked up around me. I called for the shadows of the forest to aid our plight. A wolf howled and the trees began to sway. The loggers shrank into a tight group and I used this moment to approach their bonfire. I gathered a recently added branch and threw it through the window of the bar trailer. A great and immediate roar arose and flames licked the ceiling. The men ran to the dry rivers with buckets, but pulled only mud.

The four of us made for the woods.

We walked for days stopping only briefly against the shade of Sitka spruce while I gathered berries. We helped each other over ridges and boulders using the little strength left to carve our path into the stubborn hillside.

Four days later, approaching Akutan, we passed Lukaa’s abandoned cabin. A single candle still burned in the window, so he requested we take shelter there. Inside and safe, he looked at the walls overtaken by moss and growth, and I saw in him a pain that will never be undone. Homecoming meant a chance at redemption and our village would embrace his return. All of them.

That night, the land was calm. The wind carried whispering voices and the trees pointed to the stars with broken arms. We built a fire with their discarded branches. Everyone settled in.

On the far windowsill beside the candle stood a small carved totem. A man held a gun. His eyes were hollowed out and filled with shadow. The napaq angun.

The forest had spoken, and it would only be a matter of time before it rose again to finish the job.

As our group ventured into sleep, I approached the single burning candle and, wrapping my tattooed palm around the flame, snuffed it out.

About the Creator

W. Tyler Paterson

W. T. Paterson is a four-time Pushcart Prize nominee. His work has appeared in over 90 publications worldwide including The Saturday Evening Post, The Forge Literary Magazine, The Dalhousie Review, Brilliant Flash Fiction, and Fresh Ink.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.