The Stuff that Dreams Are Made of

Sail West Young Man

There are two ways to profit from a gold rush. The suckers will head for the hills with their gold pans dreaming of wealth in the silt, grit, and muck of frigid streams. The thinking man will set up shop in the inevitable mining town. And sell supplies to the optimists full of piss and vinegar, too ignorant to know they are drawing to an inside straight. And thus it was when I opened for business as the sun rose on the line waiting at my store's door.

They were almost all men. Hopeful millionaires who had lightened their load by shedding family ties and romantic entanglements. They had dashed from farms and factories back East for their chance to live a rich man’s life. None of them yet knew that for every prospector who made enough to cover his expenses, another hundred would receive nothing but a sad lesson that effort and avarice alone rarely pave the path to wealth. A successful man needs to add forethought and a plan to his ambition.

Forethought was something I had. It was a lesson I learned by seeing my work-worn father return every evening from swinging a pick at the hard rock in upper Manhattan. He and thousands of other Irish sandhogs carved the tunnels and channels that would bring fresh water from upstate to the burgeoning metropolis. He was one of the Ulster-Irish who landed in New York in the first half of the 1800s to make a living working on construction projects altering the landscape of the New World.

When my father Jimmy, or James Daniel Sloane as his birth certificate had it, came to the city in 1823, the place was home to 150,000 souls, more people than he could imagine. When I returned from California in 1855, the population was more than 1,000,000. But I am getting ahead of myself.

In May of 1825, my father married my mother, Maura Catherine Mary Boyle. And five months after the union of the blushing bride and her strong-backed beau, yours truly set foot full of sound and fury on Shakespeare’s stage. The world may have paid little mind to the arrival of Daniel John Boyle Sloane, but my mum was delighted. My father’s reaction was less defined. To the boys at the bar, he was boastful of his reproductive endeavor. But at home, he was not so forthright in expressing his pride. At times, a dispassionate viewer may have believed he was irked at the new responsibility.

That was typical of the men in the community. In many worker’s houses in the Inwood section of Manhattan, the theory of family was tested by the reality of it. And being Protestant, they were not as resigned to the inevitability of their fate as a new wave of Hibernian Papists were.

Nonetheless, in the time before medical science intervened, the lusts of the two branches of the faith produced results in equal measure, and I was shortly joined by a younger brother, Declan. And as soon as nature recovered, the twins Abigail and Colm. It was a boisterous household. My mother was a doting servant to my father but a tough taskmaster to her children.

She had a passion for cleanliness. We were spotless children in well-worn but soap-scented clothes. And our condition, while constrained by father's earnings, was not decimated, as so many were by a man of the house oiling his philosophy with liquor at the corner tavern.

He did permit himself a beer or two on a Friday night. But his funds were limited to an allowance bestowed on him by my mother, who tended to the family finances with the same dedication she showed at her washtub.

Her most valuable lesson to me was the value of a dollar. However, it was my own insight that informed me that two dollars were twice as valuable as one. And taking good care of the one dollar does not increase the week's wages. With this knowledge of arithmetic, I pondered how I might increase the small stash of money I had squirreled away.

My first foray into commerce was a stroke of pure fortune. It was 1837. I, then a street-tough 12-year-old, was walking idly down St. Nicholas Avenue, the retail hub of the neighborhood, when I heard a tremendous din from Mr. Sweeney’s ironmongery. A rotund and irascible man, he had trouble keeping good help. In fact, no shop assistant had stayed past a month in his employment.

That Friday was no different as the noise resolved into a heated conversation between two men. Mr. Sweney was explaining to a carbuncular clerk that his efforts had fallen short of the mark; that this poor lad’s best efforts were deficient for the task. In short, Sweeny told the fear-eyed youth if he did not shape up, he could ship out. The young man contemplated the offer. And took it.

With a theatrical flourish, Mediterranean in its operatic excess, the soon-to-be ex-employee ripped off his beige full-length apron, balled it up and told Sweeney he was departing for calmer pastures. Sweeney did not ruminate on the departing worker’s announcement. He rejoined with equal vigor that if the young man wished to pursue his career elsewhere, he was welcome to do so, with Mr Sweeney’s blessing.

At least, I think that was the agreed-upon arrangement, as the spluttering proprietor chose riper expressions than are heard in tea rooms. And in his eagerness to press the point, did not leave the customary gaps between words. His communication was as clear to a passerby as Chaucer in the original is to a private school student on the first day of English class.

As the dust settled on the latest act of this play, Mr. Sweeney could be heard breathing heavily, as he hurled some decompressing imprecations, sotto voce, at the back of the departing protagonist. Turning as if to gauge the audience’s reaction, the rubicund retailer set eyes on me.

“Why ‘tis, Danny Sloane,” he said, suddenly calm. “What are you doing skulking there?”

I was not sure what skulking meant. But I was confident that I was not doing it. So I answered his inquiry.

“Nothing,” I replied.

“Do you want to earn two bits, boy?” he asked.

“I do,” I said.

“Then come with me,” he ordered.

I followed him through the door into the store. He strode past the barrels of nails, screws, fasteners, and other small items sold by the pound. He reached the counter at the back of the establishment, swung up a hinged piece of countertop, leaned it against the wall, and stepped through the gap. I followed him.

We went past the columns of drawers and assorted bins that contained brooms and clothespins, twine, and flat irons, to the small yard behind the store. There sat a pile of some 20 packing boxes.

“All right, my lad. Unpack those crates and put the stuff where it belongs.”

“How do I know where it goes?”

“Put the shovels with the shovels and the string with the twine. Use your eyes. You may be a narrowback, but you can’t be that thick.”

I was indeed not thick. I may not have been much for books, but I knew that idling didn’t put money in your pocket. So I set to the job with enthusiasm. Finding a rusty flat bar, I pried the tops off the crates. All manner of tools, notions, and thingamabobs lay coddled in straw. I decanted the contents onto an old tarpaulin I had laid over the cobblestones. And from there brought the new merchandise into the store and put like with like.

Mr. Sweeney surveyed my progress with a gimlet gaze. Each time I made a noise, he would yell at me not to break whatever I was carrying. Which seemed an unlikely event as I was stocking pick-axes and other hefty items that seemed impervious to casual damage. But to Sweeney, every load was Waterford glass to be treated like an aristocrat’s baby. And he was not shy about sharing his opinion on my cavalier ways.

I put everything away. And having finished, found an old broom, swept the yard clean of stray straw, and stacked the empty crates. Surveying my work, Sweeney offered me the compliment of silence. I soon discovered that finding no fault was as close as the crusty old bastard got to a thank you.

He reached into a metal box under the counter and recovered a quarter which he tossed to me, saying,

“If you stop by tomorrow, there may be more where that came from.”

I left and when home to the small, dark, but immaculately clean rooms where my parents and siblings lived on top of each other. I had debated spending some of my newfound wealth on myself. But the desire to show my mother that I was somebody worth a wage was too strong to resist. With proud insouciance - as if showing up with extra cash was a mere bagatelle for a boy of my quality - I placed the coin on the table and informed my mother that it was hers if she had any use for it.

She regarded the offering with suspicion. Larceny was not unknown in the neighborhood. She was concerned that her warnings of the miserable eternity that greeted sinners had fallen on deaf ears. She looked at my contribution and asked in a neutral tone where I had gotten the coin. I told her.

She gazed at me. Then deciding that she had, in fact, raised what was called ‘a good boy,’ she congratulated me on my industry. Later that evening, after we had finished the pot of cheap meat and vegetables, she told my father and siblings that they could thank their industrious relative for contributing to the family’s weal.

My brothers and sister were indifferent. And my father looked at me as if I had betrayed some ancient code by going behind his back and giving the money to my mother. But he made no audible protest as my mother was the one who decided who would give what to whom in our house.

My employment continued with Sweeney the next day. He gave me rags to dust the stock and showed me how paraffin wax could give metal an alluring shine and linseed oil could liven wood. I worked industriously all day. And my efforts could be seen as the dull, dusty merchandise succumbed to my elbow grease.

At first, a small corner of the establishment shone like a small island in polluted waters. Hours later, the effect of my labor gleamed through fully a tenth of the establishment. Sweeney would periodically wander by and yell at me for the practice. But I ignored him. At the end of the day, he handed me two dollars.

In my estimation - and I knew little then about wage scales - this put me in the upper echelons of the working man. In reality, it was not a bad haul for an adolescent. Sweeney, for all his ill temper, was not a cheat. The arrangement proved satisfactory to the both of us. And soon, I worked at the shop six days a week.

I was a personable youth who, thanks to his mother’s ministrations, people considered clean and presentable. So much so that Sweeney soon allowed me to talk to customers and ask what they were looking for. I listened to what people wanted and, with growing knowledge, would suggest the things that dovetailed with their needs.

I was especially fond of caring for the young wives looking for just the right tea trays, cooking pots, and other domestic items that might give them stature with the neighbors.

Just over two years later, the day after I celebrated my 15th birthday, Sweeney told me he was stepping out, and I was to run the store for the few hours he was gone. It was a significant moment for us, as he acknowledged his ultimate trust in my honesty. I was to be left alone with the cash box.

I did not disappoint him. I was scrupulous to the last penny. I kept a log in my copperplate script - it is an odd paradox that the ill-educated often have good handwriting. I accounted for every dollar I received and the change I handed out. I listed everything I sold and kept a running tally of how much of each item was left.

It became a point of pride for me that the store was never out of the items we stocked. If a supplier proved unreliable, I would tell Sweeney he needed to find a different wholesaler. It was tough at first, as he did not like change. He embraced the philosophy that it was 'better to stick with the devil you knew.'

I was equally loyal, but my concern was the customer. Sweeney grudgingly saw it my way. And his hesitation gave way to enthusiasm as he saw the increases in both trade and the weight of the cash box.

I was equally rigorous in getting rid of those items that collected dust. I designated an area of the store for discounted merchandise. Items that had sat on the shelf since before my employment I stacked under signs extolling their new low price. Soon the store carried only those things people wanted.

By 1843, as I turned 18, I was in charge of all the buying. We had taken on three new men to meet the increasing demand. When a haberdasher next door went out of business, I told Sweeney to buy that shop and expand. He grumbled at the expense and risk. But his concern was superficial and a distant echo of his erstwhile titanic temper.

We had agreed a few years ago, with no words being spoken on the subject, that he could yell at me once a week to keep his hand in. I would wait patiently until he had said what he must and then go on about my business.

When we first took on the extra help, he reverted to his old way of voluble insults. But I put my foot down and explained that, as I was now his manager, he would kindly direct his instructions to me. And I would make his desire known to the others. Assured that he could still make noise periodically, he tacitly agreed.

In fact, he went further and would regale the new hires on how things were when he was young and starting out. I began to wonder if they would not prefer to be yelled at instead. However, we established a profitable modus vivendi, and harmony reigned.

As part of the expansion into the new store, I suggested we carry books. Literacy was taking hold in the neighborhood. The children of illiterate immigrants were often eager learners. And knowledge became something to show off about.

Initially, we carried mostly religious texts and histories. But I could not ignore the demand for the story books some people called novels. And soon the book side of the business proved its worth. Ever curious, I started reading myself. I was like a thirsty man at an oasis. Soon I could talk with most about the government, law, philosophy, and the natural sciences.

The works of young English author Charles Dickens were popular. And copies of the Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, and Nicholas Nickley sold by the dozen. The newly literate also enjoyed local boys like James Fenimore Cooper and Edgar Allen Poe.

I kept my eye on the news. Men, not much older than me, tired of the noise, dirt, and the city's closeness, looked West. New immigrants skipped the East Coast and headed directly for the middle of the country and further afield. Arkansas and Michigan had just been admitted to the Union. And flat fertile lands beyond them attracted a new wave of immigrants speaking strange European languages.

I was not inclined to follow them. At 21, in the year of our Lord 1846, I was richer than my parents. I rented my own small lodgings. Sweeney was a mere figurehead at the store. On reaching my majority, he agreed to sell me half the business for the money I had saved and a promissory note based on future profits.

He came to the store - which now occupied four buildings and employed 30 people - no more than one or two days a week. He had bought a carriage and married an attractive young widow. He enjoyed life as a man of property whose income was earned by others. Not that I begrudged him his good fortune, as we had both profited handsomely from our mutual endeavor.

I had no particular long-range plan except to continue doing what I was doing. I considered starting a wholesale business or perhaps a tool-making concern. I belonged to the local merchant’s group where wise old men and eager upstarts shared my dreams of expansion and prosperity.

I lived in the largest, richest city in the country. Thousands of new residents needed to buy stuff. Few businesses sold it better than mine. I was happy, prosperous, and set to embark on a middle-class career. But I had an itch.

I could see the rest of the continent in my imagination. Illustrated magazines reproduced paintings of open plains and towering mountains. And as far away as the Pacific Coast, English speakers, and their European cousins were establishing new towns to take advantage of the trade in lumber and animal pelts.

Business begets business. The people who struck out to make their fortune mostly failed. But the ones that succeeded attracted others. And as more people made money, the more things they bought. It was an attractive proposition to a man who made a living by selling stuff. But it was all so distant. And nothing more than grist for idle thought.

Then in the spring of 1848, news arrived back East that gold had been found in a remote place called Sutter’s Mill in California. The effect was electric. The discovery gave substance to dreams of riches. For many, facing a wage slave life, the idea that a career’s worth of wealth could be realized in a few months was irresistible.

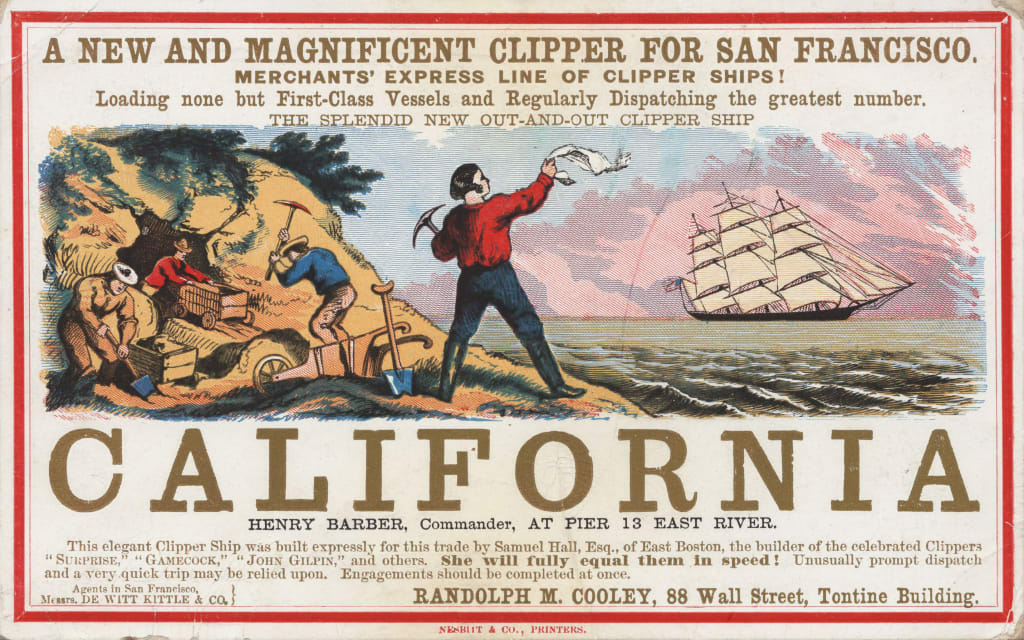

On the East Coast, thousands made plans to board ships. In the center of the country, others eyed the overland route. The news traveled globally. From ancient countries to new colonies, the lure of the precious metal was all-consuming. And so it proved for me.

I was not interested in the gold. I had made my money by selling to other people looking to make their fortune. At over 200 years old, New York was extremely wealthy. But those two centuries had allowed fierce competition for that wealth. Out West, if providence prevailed, there would also be incredible wealth. But an ambitious man, who knew what he was doing, would find little competition from seasoned opponents.

How to take advantage? California was remote but not uninhabited. Spaniards had established missions there some 70 years before. In 1846, two years before the news of gold, Americans had raised their ‘Bear Flag” over Alta California, as the Mexicans called it when it was a Mexican state, and declared that henceforth it would be the Republic of California. The Mexicans did not strenuously object as they had mostly abandoned the place anyway.

Should I go, I had no desire to get to California and find myself with nothing to sell. Which meant I had to bring goods with me. I had little idea of the difficulties and dangers of a cross-continent trek. However, the merchant in me knew I could never carry enough stuff overland to make a difference. Which left the sea route.

It is easy to decide when there is only one choice. So I chose to take a ship loaded with my merchandise from New York to San Francisco. And to ensure I would have the means to rent, buy, or build a store, I planned to bring gold. The irony was not lost on me.

My mind made up, I moved with deliberate speed. I could plan on the 15,000-mile voyage taking around 120 days on a clipper ship. I could have saved money taking a ponderous freighter. But I was a rolling stone, and the spoils go to the swift.

I negotiated with the owners of the Flying Banshee, a 10-year-old, 1,880-ton, 225-foot greyhound of the seas. We came to an agreement that both parties thought favored the other - so a good one. I hired a warehouse near the docks and stored everything I could buy that prospectors would need.

In the last week of June, stevedores loaded the Banshee with 1,213 crates of goods. This represented my total net worth, barring the gold I would carry to finance my initial operations. I had made arrangements by mail - a process that took months before the telegraph spanned the continent in 1861 - with an agent in San Francisco. Through him, I rented another warehouse near the docks, where I would store my goods until I found a suitable store.

The passage was rough. I was not a sailor. I had not even made the cross-Atlantic trip my parents had made when they were younger than I am now. It is sometimes said of successful men that ignorance played a critical role in accumulating their fortune. Perhaps there is some truth to the philosophy that being unaware of the difficulties of doing something is a powerful aid to doing it.

Had I known that the Cape of Good Hope was a grey expanse of often fatal, oily water whipped to foam by winds frozen by ice, I might not have been so venturesome. My business skills were useless. You cannot negotiate with nature.

On deck, I could breathe fresh air but at the price of permanent damp and salt-abraded red-raw skin. In my cabin, I was sheltered from the wind but enveloped in a tar-redolent miasma. Suffering from incipient nausea. I could have opened my port hole, but that would have combined the worst of the two hells.

All bad things pass. As I contemplated a quick death to spare me further misery, the Banshee turned North. The winds calmed. And as someone in the Southern Hemisphere for the first time, I enjoyed lengthening spring days in mid-September. Six weeks later, we reached San Francisco.

The first time I saw the port, it was a small town perched at the north end of a promontory that divided the Pacific Ocean from a sheltered bay. It seemed like more people were waiting on ships to disembark than were already on shore. The captain lowered the pinnace so I could get ashore to meet the port agent I had commissioned as my advance man.

Francis McGuire spoke with a hint of the brogue common in my hometown. His speech also featured the sibilant Ss and rolling Rs of the Hidalgos that first colonized this foggy land. He was a man of excellent humor and an honest face that hid the soul of a thief.

It was with great regret he informed me, as he spread his hands and shrugged his shoulders, that the rent of my storehouse had increased due to unforeseen demand. He explained that he had tried to reason with the owner. But that skinflint bastard retorted he was a slave to the market, and besides, what could he do?

It was not the first time that I had renegotiated a deal. And this time the threat of legal action was not my ally. Even if I could find a judge that would agree I was owed what I had been promised, in the interim the boxes containing my stores would have been piled up on some desolate land exposed to weather and the light fingers of the thieves drawn to new wealth like suitors to a virgin.

I had not made my money by troubling the Lord with my worries. I was a man with a longer-range view. So I asked my new associate if he knew what the price of the building might be should someone want to buy it. It did not take long for McGuire to answer with an outrageous figure. It turned out that it was the old highwayman himself who owned the damn property.

It was the start of a beautiful and profitable friendship.

The deed done, McGuire employed the necessary labor to cart the ship’s contents to my new warehouse. Settling in, I set about building a storefront to display my goods. God alone knows where McGuire found carpenters willing to forego the dreams of easy wealth and instead earn an honest crust with manual labor. But he did. Although, in fairness, the fortune these woodcutters charged me must have salved the pain they felt from forgoing all that gold.

The ship traffic increased and matched the constant stream of new overland arrivals. The town was a Tower of Babel housing all manner of tongues from the impenetrable sing-song of the Chinese to Teutonic imperiousness and even the marble-mouthed monotone of the younger sons of impoverished English aristocrats.

Three months later, I opened my new establishment. And overnight, the tide turned on the flow of my gold. The clamor of a multitude reversed a spring flood of expenses. In New York, having the right merchandise sold by friendly and knowledgeable clerks allowed the attentive business owner to charge a small premium for his goods. In San Francisco, there was little competition, and my prices reflected the scarcity. What could be haggled down to a dollar in the East was cheap at five dollars in the West.

In those early days, my store was open around the clock, seven days a week. My ship-borne merchandise primed the pump, but soon my biggest challenge was resupply. Luckily, the draw of wealth attracted artisans, tradesmen, manufacturers, and finishers. They charged me an Archbishop’s ransom, but it was a cost soon passed on to men desperate to make good.

I read later that these industrious lads panned and dug 750,000 pounds of gold in Northern California - worth at prevailing prices $248,000,000. I wanted as much of that as I could legally extort.

I divided my business into two. A wholesale operation that I kept close to my heart and a retail concern. I made McGuire a partner in the retail end. Giving that buccaneer a share of the profits was cheaper than paying his piecemeal rates for every goddamn thing.

By the end of 1849, McGuire and I had opened three stores in San Pedro, Colima, and Doylestown. Bringing the business to the Sierra Madre foothills was a boon to my margins. What sold for five dollars in San Franciso went for seven close to the mines.

Even though McGuire did the heavy lifting when it came to the inland stores, I like to tour them once a month to sense the drift of the business. And thus it was in 1850 when I opened for business as the sun rose on the line waiting at my Colima store's door.

I was already a millionaire. And, although I did not know it then, there were five more years of gold left. As the 1850s ripened, more competition for the forty-niner’s dollar arose. Business matured and came to resemble the polite brawl of my old hometown. Courts and contracts sprung up. And lawyers enforced what had once been policed with lead pipes and knives.

In 1854, at the peak of the rush, I sold the business, padlock, gunstock, and nail barrel to McGuire. Within a year, the gold was gone. And by 1856, I was back in New York a rich man. I bought a fancy carriage and kept company with a beautiful young widow. I sat on the boards of various civic and charitable concerns and enjoyed my retirement.

I was wealthy beyond my youthful dreams. And had just turned 31.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.