Al-Ma'mūn's Legacy

Baghdad's Golden Age

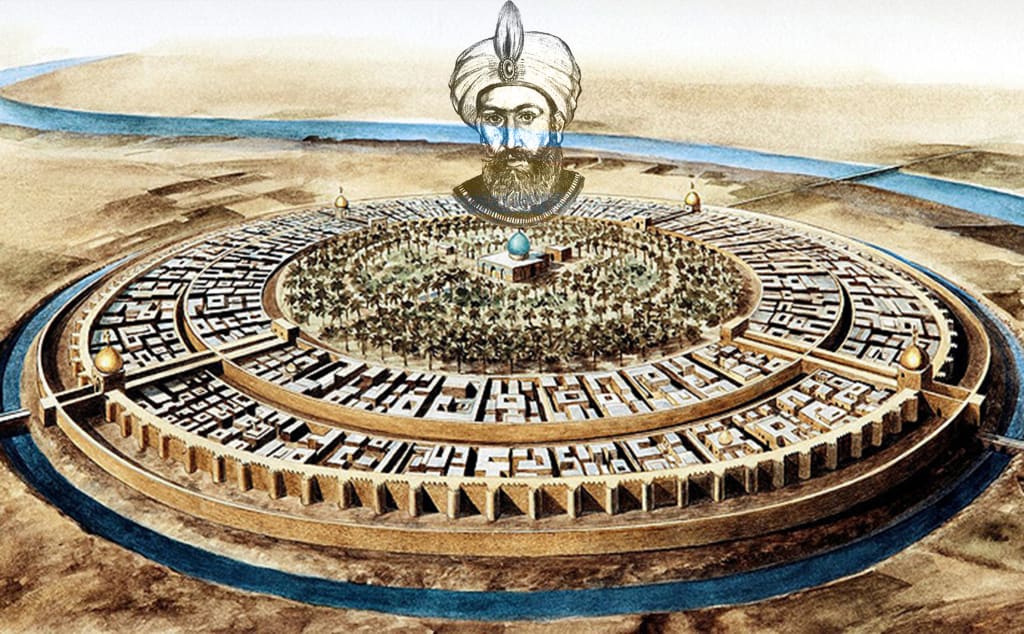

Nestled in the heart of Baghdad lies the historic district of Bab al-Sharji, its name, "East Gate," reminiscent of medieval fortifications erected in the early 10th century. A fleeting British presence during the closing stages of World War I saw the gatehouse transform into a garrison church, referred to as the South Gate, with the Bab al-Mu'atham, its counterpart to the north. Sadly, none of these medieval walls or the East Gate endure today. Yet, the mere mention of Bab al-Sharji invokes a vibrant picture of a bustling square, teeming with life, food stalls, and second-hand record shops surrounding a busy bus depot and taxi ranks. This district's name serves as a poignant reminder of Baghdad's storied past, from its founding in 762 CE as the new seat of power for the formidable Abbāsid Empire.

Over the centuries, Baghdad has weathered the ebbs and flows of history, its governance center shifting back and forth across the Tigris River as successive rulers erected their grand palaces. Despite the modern hardships faced by its inhabitants, Baghdad boasts a rich history, having once reigned as the world's most opulent, grandiose, and proud city for five centuries. My own birth in a Baghdad hospital in Karradat Mariam, near the present-day Green Zone, marked precisely twelve hundred years since the city's inception.

Notably, one of Baghdad's most illustrious rulers, Abū Ja’far Abdullah al-Ma’mūn, takes center stage in this narrative. Al-Ma’mūn is a central figure in our story, as he emerged as the most influential patron of science among Islamic rulers, catalyzing an extraordinary era of scholarship and learning. To understand the catalysts of this golden age, we must delve into the psyche and motivations of early Muslim society, examining the internal and external forces that shaped this transformative period. But before embarking on our journey, let me introduce you to this remarkable caliph.

While al-Ma’mūn was not the only caliph supporting science, his passion, cultural appreciation, and encouragement of original thought set him apart. Hailing from a lineage of notable caliphs, including his father, Harūn al-Rashīd, who maintained diplomatic ties with Charlemagne and expanded the influence of the Abbāsid Empire, al-Ma’mūn and his father were pivotal figures in a dynamic period of cultural exchange.

This era witnessed the exchange of precious gifts, like an elephant and an intricate brass water clock, between al-Rashīd and Charlemagne. Al-Rashīd's legendary wealth and gem collection were renowned, and he oversaw military campaigns against the Byzantine Empire, securing tribute payments from defeated emperors. However, his administration in Baghdad owed much to the influential Persian Barmaki family.

Al-Ma’mūn's origins were more modest; born to a Persian slave concubine, he was raised by the Barmaki family. His father's palace, the Qasr al-Khuld, was an imposing structure, and his upbringing differed markedly from that of his half-brother, al-Amīn, born to an Arab mother, Zubayda. Nonetheless, al-Ma’mūn enjoyed his father's affection and a privileged upbringing.

As he matured, al-Ma’mūn immersed himself in a diverse array of studies, mastering Arabic grammar, mathematics, philosophy, and the art of dialectic debate and theology known as kalām. These pursuits profoundly influenced his lifelong passion for science.

By the 9th century, the youthful prince beheld Baghdad at its zenith. The city was renowned for its intricate Abbāsid architecture, vast palaces, and a population exceeding a million. Baghdad had outshone the grandeur of Rome, Athens, and Alexandria, becoming a testament to the power and prosperity of the Abbāsid Empire.

With the passage of time, the turbulent history of early Abbāsid Baghdad has left scant remnants today. Unlike Rome and Athens, Iraq lacks stone quarries, though once rich in limestone and marble deposits. Baghdad's edifices, including grand palaces, were predominantly built from sun-dried mud bricks, rendering them susceptible to the ravages of invading armies, fires, and floods. However, echoes of that bygone era can still be heard at the Palace of Ukhaidhir, located about 120 miles south of Baghdad, a rare testament to the Abbāsid legacy.

Baghdad's palaces, often clustered along the Tigris River, featured multi-story structures adorned with intricate weathervanes symbolizing the caliphs' might. Inside, marble, ceramics, and ornate tapestries adorned the interiors, providing an opulent backdrop for family gatherings on embroidered cushions. This grandeur contrasted starkly with the cramped, sun-dried brick buildings of the less privileged.

Regardless of social strata, Baghdad remained a well-kept city with clean streets and intricate canal systems ensuring a constant water supply. The air carried the fragrances of spices, perfumes, and the grilled freshwater carp, shabbout, a local delicacy.

Nevertheless, modern Baghdad has faced a parallel tale of war and upheaval, akin to the Baghdad of al-Ma’mūn's youth. The tumultuous conflicts of the late 20th century disrupted its tranquil beauty, leaving the city's infrastructure in ruins and its former glory diminished. In both historical eras, turmoil concluded with a change in the ruling authority.

The tale of al-Ma’mūn's rise to power intertwines with the fate of his brother, al-Amīn, and the intricacies of succession politics. Despite al-Ma’mūn's suitability, al-Rashīd, influenced by those around him, chose al-Amīn as his heir, a decision he enforced ruthlessly, even executing al-Ma’mūn's close associate, Ja'far. Yet, the gift of Khurasan to al-Ma’mūn hinted at a hidden agenda, enabling him to challenge his brother. Al-Rashīd's motives remain a subject of speculation.

The pivotal moment arrived in 805 when a rebellion erupted in Khurasan, paving the way for al-Ma’mūn's ascent to power. His astute governance, coupled with the support of his confidant al-Fāthl ibn Sahl, aided in quelling the rebellion and consolidating his authority. Meanwhile, he bolstered his public image, laying claim to the caliphate in Baghdad from his brother, al-Amīn. As he embarked on his quest for power, al-Ma’mūn laid the groundwork for a new era.

The newly appointed caliph embarked on a bold campaign to establish his authority in the East. He confronted his brother, who governed Khurasan, demanding the transfer of tax revenues to Baghdad. He also called back loyalists of their father, al-Ma’mūn, who remained with the original army, and designated his son as the direct heir, superseding his brother. The escalating friction between the siblings appeared headed towards armed conflict, and soon, the capable Persian General Tāhir

About the Creator

Muhammad Mohsin

I'm a writer weaving words into worlds, an artist, singer, poet, storyteller and dreamer. Let's explore new dimensions together through the power of storytelling

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.