Women on the Market in Westeros

Feminist Study of "A Song of Ice and Fire"

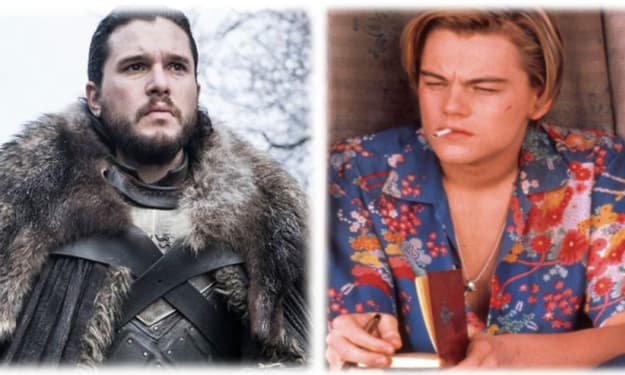

Over the past several years, Western popular culture has seen an explosion in interest for the fantasy genre, erupting in 2011 when HBO premiered the television drama Game of Thrones. In the history of television, the popularity that Thrones has reached is unrivaled. The drama series and the books it is based on have both been praised for their intricate weaving of many plotlines, genres, and thematic specialties. As with any popular culture phenomena, Game of Thrones was privileged enough to have their own creative platform in which they can perform social critiques. While most of these criticisms are placed in a medieval and/or fantasy context, many lessons provided by Thrones are still relevant to its twenty-first century fan base.

From the time the show premiered, it has been admonished for its portrayal of women and its lack of feminist qualities. Sexism runs rampant in all of the Seven Kingdoms of Westeros, with most of the social norms and customs based off of the inherent ‘trade value’ of the female population. No woman is safe from the predatory nature of Westerosi men—high or low born, lady or whore, noble or peasant. It is the transaction and exchange of women that makes life in Westeros, and its neighboring continent, Essos, possible. When looking at the series through this lens, it is easy to apply Luce Irigaray’s essay “Women on the Market” to the context of the female characters who inhabit that world. Irigaray’s essay presents the argument that women are just as easily exchanged by men as any other commodity. Although her thesis is more abstract in the real world, it is extremely evident within the world of Game of Thrones, where the functional nature of society is predicated on whether or not women can be married and reproduce. This is especially true of three popular female characters—Sansa Stark, Cersei Lannister, and Daenerys Targaryen, all of whom have endured their fair share of abuses from men. How do men use the institution of marriage to exploit these women for their own political and personal desires? Through what agency do the aforementioned women seek to liberate themselves from the metaphorical market? These are the main questions that this paper will inquire into. Although this paper will primarily examine and analyze events from the novels, incidents from television series will also be referenced.

Before turning to each individual analysis, I will provide brief background information of the character, beginning with Sansa Stark. When audiences first meet Sansa, she is a whimsical and dreamy young girl (eleven in the books, thirteen in the series). Her mother, Lady Catelyn, hails from the paramount family of a kingdom called the Riverlands, while her father, Lord Eddard/Ned Stark, is the highest lord of the largest of the Seven Kingdoms—the North. The Starks reside in the ancient castle of Winterfell, where Sansa and her siblings (Robb, Arya, Bran, Rickon, and half-brother Jon Snow) grow up. Sansa, whose beauty and ladylike talents are constantly emphasized, is often held to a higher standard than her rowdier younger sister Arya, due to her more traditional feminine interests.

Sansa’s objectification begins immediately after the series begins; her sole narrative purpose in the early events of the series is predicated on her marriageability. When her father’s best friend, King Robert Baratheon, arrives at Winterfell early in the series, he hastily arranges a marriage between Sansa and his eldest son, Prince Joffrey. In Eddard’s first conversation with Robert, the latter proposes the engagement suddenly, stating, “I have a son. You have a daughter. My Joff and your Sansa shall join our houses, as Lyanna and I might once have done (A Game of Thrones 39)”. Robert arranges this betrothal not only out of political interest, but a personal one as well, as marrying Sansa to Joffrey allows him to hold onto his romantic ideal of his former betrothed, Lyanna Stark. The exchange occurs between Robert and Sansa’s father, without any input from the potential bride-to-be. The nature of the transaction harkens back to a point made by Irigaray, in which she states:

The production of women, signs, and com¬modities is always referred back to men (when a man buys a girl, he "pays" the father or the brother, not the mother...), and they always pass from one man to another, from one group of men to another” (Irigaray 171).

While Sansa herself is initially ecstatic over the match, it is due to the fact that she is unaware of the political and social institutions that make the marriage plausible. Her betrothal presents the first of many instances in which Sansa is bargained off for political purposes. The engagement to Joffrey was not made out of love, but out of Robert’s desire to bind Houses Stark and Baratheon together politically, although this alliance was all but cemented due to Ned Stark’s newfound status of Hand of the King. Robert and Ned have had a brotherly relationship for years, marrying Sansa to Joffrey is nothing but a metaphorical stand in for Robert’s broken engagement to Lyanna.

Sansa’s objectification only heightens as the plot continues. The second novel sees Sansa’s engagement to Joffrey broken, effectively placing the young girl back onto the market. Instantly, noble lords and ladies scheme to use her availability to their advantage. She is primarily victimized by Lord Tywin Lannister and Lady Olenna Tyrell. The latter covertly seeks to wed Sansa to her eldest grandson and heir to all of the lands of a region called the Reach—Willas Tyrell. As she did with Joffrey, Sansa immediately romanticizes the notion, understandably longing to be free of King’s Landing. Sansa tells her friend—the new court fool, Ser Dontos—of her secret, impending betrothal. Despite his lowly status, Dontos clearly sees through the Tyrells schemes, stating: “You cannot!” in a voice as thick with horror as with wine. “I tell you, these Tyrells are only Lannisters with flowers…these Tyrells care nothing for you. It’s your claim they mean to wed.” (A Storm of Swords 184). Sansa is visibly confused by his argument, until he reminds her that she is indeed the heir to Winterfell. The attempted machinations of the Tyrells prove that Sansa is nothing but a pawn in the game of thrones; no one around her truly cares for her wellbeing, but mean to exploit her name and status to their advantage.

The primary manifestation of Sansa’s marketability comes when she is wed to Tyrion Lannister in the third novel of the series, A Storm of Swords. Despite the Tyrells’ best attempt at subterfuge, Lord Tywin Lannister eventually catches wind of their plot to marry Sansa to Willas. He admits to his son, Tyrion, that he is worried about a potential Stark/Tyrell alliance, and seeks to prevent it. In order to do so, he plans to marry Sansa to Tyrion, effectively bringing nearly all of the major regions of Westeros under his control. Tyrion himself is appalled by this arrangement, objecting to it on account of Sansa’s young age. Lord Tywin refutes this argument by claiming: “Your sister swears she’s flowered. If so, she is a woman, fit to be wed. You must needs take her maidenhead, so no man can say the marriage was no consummated. After that, if you prefer to wait a year or two before bedding her again, you would be within your rights as her husband” (A Storm of Swords 220). Both plots negate Sansa’s own autonomy as a human being; she is viewed as a means to end, a pawn used to secure power over Winterfell and the North. Tywin is not viewing Sansa as a human being; she is valuable only for the sum of her claim, useful for nothing but granting the Lannisters an heir through which to rule the North. The above quote sees Tywin concerned only with Sansa’s virginity, a trait on which her marriageability solely relies, and her menstruation, in order to be certain that she can produce the heir he needs. Her eventual (albeit brief) marriage to Tyrion allows to Lannisters to use her as an instrument to defeat her brother, King Robb Stark, with whom they are at war. Although Tyrion treats her well, and he is being forced into the marriage as much as she is, he still sees her as a tool to utilize to his own personal desires, thinking to himself: “A wife might be the very thing he needed. If she brought him lands a keep, it would give him a place in the world apart from Joffrey’s court…and away from Cersei and their father” (A Storm of Swords 220). Despite Tyrion’s equivalent status as a pawn in his father’s plots, Sansa is a way for him to receive distance from the court of King’s Landing; he views her simply as a wife, not as another human being manipulated into the same situation.

Although the novels published to date represent Sansa’s market potential, the television series further emphasizes said potential. The fifth season of the series sees Sansa married off the sadistic Ramsay Bolton, an occurrence not present in the novels. Ramsay, born a bastard, was recently granted legitimacy into the Bolton family by King Tommen I Baratheon . His father, Roose, had betrayed Robb Stark and was granted the title of Warden of the North for his service. These events resulted in Ramsay becoming the heir to Winterfell and his father’s newfound position. In order to cement the Boltons’ status as the new ruling family of the North, Roose schemes with Lord Petyr Baelish to marry Sansa to Ramsay. Sansa’s status as the daughter of the last Lord of Winterfell aids in solidifying the Boltons’ position. Unfortunately, Sansa’s status as a commodity is never more present. Ramsay unashamedly abuses and rapes her as a means to procure an heir and commence the Stark/Bolton line. After Sansa’s escape (coinciding with the birth of his second son) at the beginning of the sixth season, Roose threatens to remove Ramsay from the line of succession unless he can find Sansa and produce an heir. Although this never comes to pass, as the Boltons are ousted from power by Sansa and her half-brother, Jon Snow, her only significance to the Boltons was her name, her body, and the social standing that a marriage to her could bring. Ultimately, Sansa uses the political skills she learned in King’s Landing, as well as the show of strength she used from publicly executing Petyr Baelish, to be chosen as the Queen in the North. Sansa’s ascension as queen of her homeland, in her own right, is an appropriate end to her taxing character arc in which she had been continually brutalized and manipulated by men.

Sansa’s personal experiences are often paralleled by her one-time mentor and longtime captor, Queen Cersei Lannister, who is painfully aware of her position on the marriage market (far more so than Sansa). In terms of necessary background knowledge, Cersei is the only daughter of the kingdom’s wealthiest lord, the formidable Lord Tywin, and therefore has immense potential and promise on the “market” of Westeros. At the end of the rebellion that preceded the main events of the series, Cersei weds the new king Robert Baratheon after he successfully ousts the sitting monarch, Aerys II Targaryen. The marriage is based off political desires only, as a way for Lord Tywin to ensure his loyalty to the new king on the Iron Throne after sitting out the majority of the war. While Cersei is initially thrilled with the marriage, her excitement quickly turns sour after Robert proves he still desires his deceased ex-fiancée, Lyanna Stark. It is after this incident that Cersei rekindles her sordid, incestuous affair with her twin brother Jaime—a potentially deadly relationship that Cersei goes to great lengths to keep under wraps. For the duration of her marriage (ending with Robert’s death), Cersei endures her husband’s mistreatment and abuse by continuing her sexual relationship with Jaime, which eventually results in their three children—Joffrey, Myrcella, and Tommen ‘Baratheon’ . Once her eldest son ascends to the Iron Throne, Cersei loses her title as queen consort and is therefore eligible to re-enter the trade market of women.

Cersei’s value stems from her noble birth and singular beauty—two traits her father uses to his political advantage without regard for her desires or status as queen. In both the book and television series, Lord Tywin uses Cersei’s widowhood in order to throw a wrench in the aforementioned plans of his political rival, Lady Olenna Tyrell, who had planned to marry her grandson to Sansa Stark. Upon hearing the secret news, Lord Tywin effectively swoops in and betroths Cersei to the Willas Tyrell, denying Lady Olenna the opportunity to wed Sansa to him. This enrages Cersei, who has long attempted to free herself from the shackles of traditional femininity, and places herself above the commodity market of women by asserting her status as queen. In defense of herself, she argues:

It came so suddenly that Cersei could only stare for a moment. Then her cheeks reddened as if she had been slapped. “No. Not again. I will not.”

“Your Grace,” said Ser Kevan, courteously, “you are a young woman, still fair and fertile. Surely you cannot wish to spend the rest of your days alone? And a new marriage would put to rest this talk of incest for good and all.” (A Storm of Swords, 218).

This exchange, taking place in the thick of the disastrous War of the Five Kings, proves the complete male disregard for the desires and feelings of women. Cersei continues to rage against her father’s schemes, arguing herself above being sold off to another husband by declaring, “I am Queen of the Seven Kingdoms, not a brood mare! The Queen Regent!” (A Storm of Swords, 218). Cersei’s declaration against her father is an extremely daring move in-universe, as women were expected to be submissive to the requests of their male relatives. Lord Tywin eventually cows Cersei into doing his bidding, citing the need to strengthen their allegiance with House Tyrell in order to defeat his main militaristic rival, Stannis Baratheon. A quote from Irigaray is aptly appropriate here, as she states:

A sociocultural endogamy would thus forbid commerce with women. Men make com¬merce of them, but they do not enter into any exchanges with them…exchange of women as goods accompanies and stimulates ex¬changes of other "wealth" among groups of men (Irigaray 172).

Ultimately, Cersei’s engagement never comes to pass due to Lady Olenna Tyrell and Petyr Baelish’s murder of King Joffrey, and Tyrion Lannister’s subsequent murder of their father. After those deaths, Cersei obtains even more power by working through her pliable youngest son Tommen, who ascends the throne after his brother’s death. It is telling, however, that despite her son’s young age, he is still considered the ultimately authority; Cersei must still take pains to rule the kingdom through him, giving the indication that the country would rather listen to the decrees of a young boy rather than a woman.

Cersei, in her best attempts to remove herself from the marriage market, inadvertently places herself on it in the most extreme manner yet. Her actions as Tommen’s regent allow the Faith Militant, an overzealous religious sect, to be reborn throughout King’s Landing. Shortsightedly, she arms these godly fanatics as a way to dispose of her political rival, Margaery Tyrell. Cersei aims to plant evidence of Margaery’s unpermitted sexual relationships outside of her engagement to Tommen. This plot ends with both women imprisoned; Margaery for false claims, but Cersei for true ones. The leader of the Faith Militant, known only as the High Sparrow, is informed of Cersei’s moral and sexual indiscretions through her cousin, Lancel Lannister, with whom she had a sexual relationship in the early parts of the series. At this point, the truth of Cersei’s incestuous dalliance with Jaime have run rampant through the kingdoms and are no longer regarded as rumors. Although she vehemently denies this while imprisoned, she is told she will stand trial for her affair with Lancel and Ser Osney Kettleblack, as well as for the role she played in Robert Baratheon’s death. Before she can stand trial, however, she must complete her walk of shame. By the High Sparrow’s own command, Cersei is required to walk naked through the streets of King’s Landing spanning the considerable distance from the Sept of Baelor to the Red Keep. Her nakedness is put on display for the entirety of the city, with commoners jeering at her and men making lewd comments about her body. It is clear that Cersei’s public nudity and shame are a form of punishment against a woman who has authoritatively embraced her own sexuality. Her acceptance of her femininity is an alarming breach of the status quo, disproving the common belief that women do not have autonomy over their own bodies. Once her ‘indiscretions’ come to light, she is promptly punished in an obscenely degrading fashion. As her walk begins, Cersei recalls how Lord Tywin had made her grandfather’s mistress complete the same task—publicly punishing a woman for daring to have her own sense of sexual liberty in a way that does not benefit them in any form. These similar instances are indicative of the way women are treated when they dare to believe they have autonomous control of their own bodies and sexual desires.

Despite the trauma her walk of shame brought her, the final two seasons of the television series see Cersei calculatedly plotting her own return to the market to serve her political interests. She has finally achieved her goal of becoming the ruling queen of the Seven Kingdoms, but her ascension to the Iron Throne coincides with exiled scion Daenerys Targaryen’s invasion of Westeros. In order to combat the formidable military force that Daenerys boasts, it is imperative for Cersei to make allies. In an interesting turn of events, Cersei puts herself on the market by offering marriage to Lord Euron Greyjoy in exchange for his naval power. Although it could possibly be read as demeaning to herself, the move is actually quite empowering. At the beginning of the seventh season, Cersei is fully aware of her value and status as the Queen on the Iron Throne. She channels her father by marketing herself to potential suitors—not only to serve her political ambitions, but to save her and Jaime’s lives, as she knows they will be summarily executed if Daenerys were to claim the throne. Instead of being manipulated by Euron, the roles are reversed; Cersei goes as far as to convince him that her and Jaime’s unborn fourth child is a result of their sexual relationship. It serves as an inversion to a quote from Irigaray, men are now making commerce with women instead of making commerce of them. Cersei’s engagement to Euron is constructed by no one but herself; it gains her multiple decisive military victories and the death of one of Daenerys’ dragons, Rhaegal. Although her television arc ultimately ends with her death, it is both liberating and refreshing to see Cersei use the machinations that oppressed her for so long to her own advantage.

The third and final character discussed is the young dragon queen, Daenerys Targaryen. Living on the other side of the Narrow Sea, Daenerys was exiled from Westeros after her father’s kingship was overthrown, travelling the vast continent of Essos with her brother Viserys, hoping to find people sympathetic to their cause and help restore them to the Westerosi monarchy. At the beginning of A Game of Thrones, the Targaryens’ caretaker, Illyrio Mopatis, has arranged for Daenerys to marry the powerful Khal Drogo, who will supply his army to Viserys’ cause in exchange for a wife. Despite her young age, Daenerys is cognizant of the nature of the transaction, thinking to herself:

Magister Illyrio was a dealer in spices, gemstones, dragonbone, and other, less savory things. He had friends in all of the Nine Free Cities, it was said, and even beyond, in Vaes Dothrak and the fabled lands beyond the Jade Sea. It was also said that he’d never had a friend he wouldn’t cheerfully sell for the right price (A Game of Thrones, pg. 23).

Daenerys, although the one to be married, has no active voice in this arrangement. Illyrio and Viserys both view her as an object; a form of currency they can exploit in order to further their “less savory” desires. In a scene from the pilot episode, Viserys’ motivations are made clear, as he states to his sister, “I would let his whole tribe fuck you. All forty thousand men and their horses too if that’s what it took”. The entire situation proves Irigaray’s thesis—that men view women as another form of commodity. Irigaray writes: “It is thus not as "women" that they are exchanged, but as women to some common feature¬ their current price in gold, or phalluses-and of would represent a plus or minus quantity” (Irigaray 174). Ultimately, Viserys’ plan never unfolds the way he desired, and his bargaining of his sister eventually ends with his death. Although she was initially powerless in her situation, Daenerys emerges from the aftermath of her forced marriage stronger than ever, and with three baby dragons. Daenerys’ unique possession of her ‘children’ allow her to be analytically separated from other noble ladies such as Cersei and Sansa. Although, it is interesting to note that her power over the dragons comes with a gendered connotation, being known as their “mother” first and foremost .

Since the conclusion of the first novel, Daenerys has been metaphorically “off the market”. The death of Khal Drogo and their child, alongside the birth of the dragons, finds her situated in an interesting position. Her possession of the dragons and symbolic status as their ‘mother’ indirectly remove her from the market. Through her position as the Dragon Queen, she is afforded powerful opportunities not available to other noblewomen, such as Cersei and Sansa. The dragons give her a stable identity, a sense of autonomy and power she would not have otherwise had. The mere existence of her children catapult her to a different realm, one that allows her to be extracted from the market. As Rikke Schubart notes: “In feminist theory, it is asserted that a female fantasy hero is but a dream” (105). Daenerys, through the dragons, is effectively placed in a god-like class of female fantasy hero to which people in canon—mainly men—attempt to use to their advantage. The fifth novel of the series, A Dance with Dragons, sees a myriad of male characters converging onto Daenerys. They all seek something from her—Tyrion Lannister desires revenge against his family, Victarion Greyjoy wants her hand in marriage, Euron Greyjoy aims to possess her dragons. In these situations, Daenerys is the one in power. They must bargain with her to get what they desire, rather than trying to use her as an instrument to leapfrog through society. Her dragons put her in her own tier, one not governed by the marriageability regulations suffered by other female characters.

Daenerys is not only removed from the market of marriage, but furthermore sets the tone of her subsequent sexual relationships with men. After her departure from the Dothraki khalasar, she begins a purely sexual relationship with the commander of the ‘sellsword’ army allegiant to her, Daario Naharis. This affair occurs both in the novels and the series; the novels depict her as a young, infatuated girl, while the television series emphasizes Daenerys’ control over their encounters. Upon their first sexual tryst, Daenerys is seen sitting back coolly as Daario undresses, watching him as she sips wine. Her controlled demand for him to “take off his clothes” is a form of sexual boldness not permitted to the other female characters of the series. She ultimately breaks off their relationship before she departs to begin her invasion of Westeros. The aforementioned sex scene, as well as the entirely of her relationship with Daario, reinforce her autonomy over her own body; she gets to choose who she has sex with, the context it occurs, and when the relationship ends.

Her arrival in Westeros finds Daenerys placing herself back on the market in order to win allies in her fight for the Iron Throne. Daenerys’ termination of her affair with Daario is predicated on making herself marketable to potential suitors upon her arrival in the Seven Kingdoms. However, the way she markets herself is not through marriage, but rather through the sheer military prowess she boasts. In this regard, she markets himself similarly to how Cersei did; she is aware of her market potential and seeks to exploit the desires of men to her advantage. She does thusly with Jon Snow, who had been recently named the King in the North. Although the two never marry, they do begin a relationship that is seemingly bent to Daenerys’ will. She plans to use Jon’s influence in his kingdom in order to defeat Cersei in the war for the Iron Throne. His authority over the North, alongside her providing military might in the war against the White Walkers, is enough, in her mind, to win the North’s allegiance. Instead of using marriage as a bargaining tool, she negotiates instead with her staggering militaristic power. This is an interesting contrast to the use of marriage, as no other woman in the series has commanded as much brute militant force as Daenerys. Ultimately, she never achieves her singular goal, and finds herself murdered by Jon after she conquered King’s Landing. Her last remaining dragon, Drogon, destroys the Iron Throne in his grief, essentially destroying the grand social institution that allowed the marketing of women to be possible.

In an editorial piece written for The Guardian, journalist Abigail Chandler cites the downfall of the popular women of Game of Thrones linked to the controversial ending of the show. She references Cersei’s codependent relationship with Jaime, Sansa’s rape, and Daenerys’ madness. So, while the show made great strides to overcome the “sexposition” that ran rampant during the first few seasons, was all of this effort offset by the divisive endings of the female characters? Do the incomplete novels, as well as the concluded television series, foreground the sexual exploitation of women at the hands of men? The answer is tricky, not falling in either a definitive ‘yes’ or ‘no’ category. The sex scenes in the initial seasons are gratuitous, but they are lifted directly from the blueprints of the novels—which serve to depict the brutality and unbalanced social culture of a feudal society like Westeros. Calling the television series anti-feminist is a stretch taking into consideration the endings of the three discussed characters: Cersei is the last sitting monarch on the Iron Throne, Sansa becomes Queen in the North, Daenerys is the catalyst for the complete elimination of a social establishment. The criticism that the show is too violent is valid, but it would be naïve to say that all of this violence stems from the acts of men; the most severe and widespread acts come from the will and decisions of its female characters. As creator George R.R. Martin claims, both A Song of Ice and Fire and Game of Thrones are about “the human heart in conflict with itself”. A story such as this does not lend itself to one-dimensional female characters, as so many feminist critiques seem to desire. The appeal of Sansa, Cersei, and Daenerys comes not from their gender, but rather from the steps they take—justified or not—to overcome the oppressive system they were born into.

Works Cited

Baumgardner, Emma. “Misogyny, Rape Culture, and the Reinforcement of Gender Roles in HBO’s Game of Thrones.” (2019).

Chandler, Abigail. “Game of Thrones Has Betrayed the Women Who Made It Great.” The Guardian, 8 May 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2019/may/08/game-of-thrones-has-betrayed-the-women-who-made-it-great.

Clapton, William, and Laura J Shepherd. “Lessons from Westeros: Gender and Power in Game of Thrones.” Political Studies Association, vol. 37, no. 5, 2017.

Gjelsvik, Anne, and Rikke Schubart. Women of Ice and Fire. Bloomsbury Academic, 2016.

Irigaray, Luce. “Women on the Market.” pp. 170-191.

Laurie, Timothy. Serialising Gender, Breeding Race: Biopolitics in Game of Thrones., University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, 2015.

Martin, George RR. A Game of Thrones. Bantam Spectra, 1996.

Martin, George RR. A Storm of Swords. Bantam Spectra, 2000.

Martin, George RR. A Dance of Dragons. Bantam Spectra, 2011.

Wittig, Monique, and Kelly Oliver. “A Lesbian Is Not a Woman.” French Feminism Reader , Rowman and Littlefield, 2000, pp. 119–123 .

About the Creator

Lauren Humphreys

writer of things • I like nerdy stuff

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.