The Writing Mistake in "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban" that Everyone Missed

The "Azkaban guards" have a little problem

One of the hallmarks of being a good author (or script writer) almost seems like a paradox: the less your audience is thinking about you, the better you’re doing.

If readers are fully engrossed in the world between the pages, they have no reason to consider the “meta,” — the real-life factor behind the author’s narrative choices.

Once the mind is dislodged from the book world and starts thinking about the real one, it’s hard to stay invested in the story at the same level.

Generally, the uber-famous “Harry Potter” series is quite adept at managing this concept. J.K. Rowling’s wizarding world comes alive, revealing to readers more and more of its inner workings at the same pace that Harry himself learns them. It’s easy to feel like another Gryffindor student, watching events unfold from across the common room or a seat in the Quidditch stands.

As engaging as these beloved books are, there are a few slip-ups along the way that can knock observant readers right out of their immersive state.

I was struck by one such shortcoming in a recent re-reading of “The Prisoner of Azkaban.” It may seem like a nitpick, and maybe it is, but when I noticed it my suspension of disbelief was significantly challenged for the rest of the novel.

So let’s dive in — in excruciating detail.

What’s in a name?

In Rowling’s third outing, the plot may seem to center on the looming figure of alleged murderer Sirius Black, but it’s really the Dementors that drive Harry’s character arc forward.

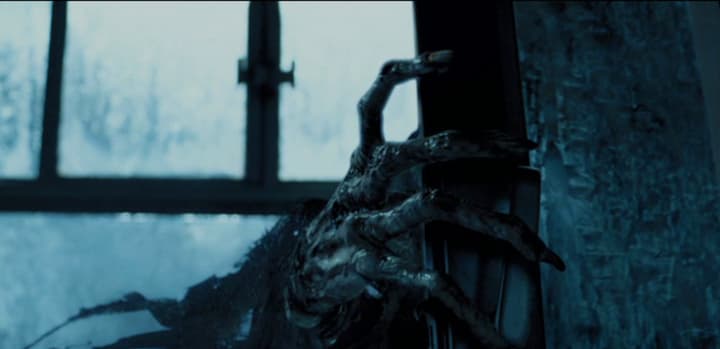

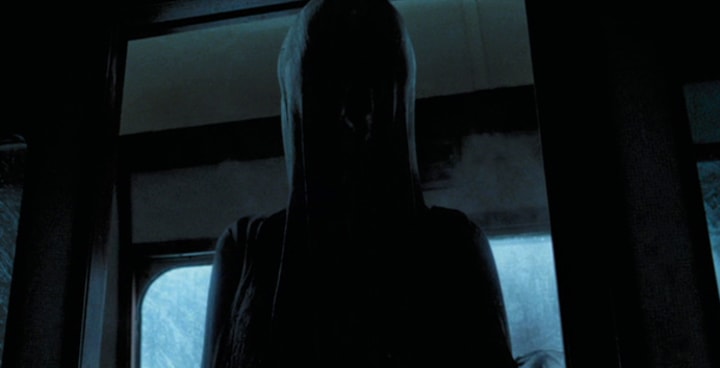

From his first encounter with the joy-devouring creatures in Chapter 5, the Dementors force young Harry to grapple with the ghosts of his past and learn to overcome fear.

But the way Rowling builds up to that memorable introduction to Dementors on the Hogwarts Express reveals a flaw in her process. In prioritizing the big reveal, she sacrificed some world integrity and believability along the way.

By the time we get to Chapter 5: “The Dementor,” Harry has already heard plenty of talk about Azkaban, the wizard prison, from magical folk who are more in-the-know. Black is on the loose, after all, and no one’s ever escaped from Azkaban before.

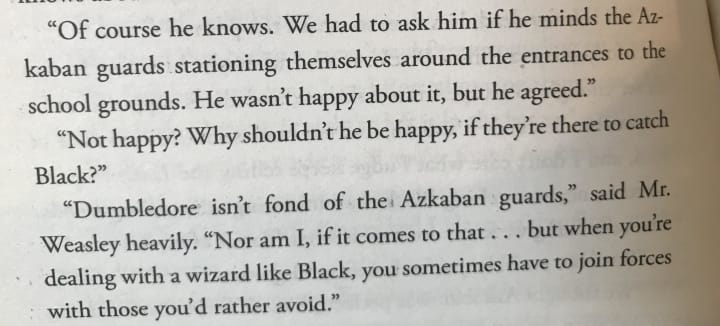

That’s because of the “Azkaban guards,” several characters say.

That phrase is how every character in the first four chapters refers to the Dementors. Then once Harry (and the reader) meets one, suddenly everyone starts calling the creatures by their true name.

I’m not exaggerating. Before Harry comes face-to-hood with a Dementor on the Hogwarts Express, four different characters refer to them as “the Azkaban guards” a total of six times, and no one says the word “Dementor.”

From Chapter 5 onward, 17 characters say “Dementor” a grand total of 94 times.

That’s right. I counted.

What’s more, once Harry knows what a Dementor is, NO ONE says “Azkaban guards” even a single time. The phrase simply vanishes. Why? Because it already served its purpose.

“Azkaban guards” was nothing but a clumsy crutch Rowling used to introduce Harry, and thereby the reader, to an abstract menace without spoiling the creature reveal in Chapter 5.

This is a fallacy I’ll be calling “writing to the reader.” From the perspective of the consumer, these phrasing choices make sense because they preserve the effectiveness of the first Dementor scene. The nature of who, or what, the Azkaban guards are remains a secret until the opportune moment.

But inside the wizarding world of Rowling’s creation, it makes absolutely no sense at all.

The evidence

To prove my claim, let’s take a look at the context around each time someone says “Azkaban guards” in the first four chapters.

Four out of six times the phrase is spoken, the speaker is either talking to Harry or knows he’s listening.

In Chapter 3, Minister of Magic Cornelius Fudge tells Harry “the Azkaban guards have never yet failed” as a way to minimize the danger and seriousness (heh heh) of Black’s escape.

In Chapter 4, Arthur Weasley tells his son Ron that “it’s the Azkaban guards who’ll get [Black] back, you mark my words.”

One could potentially argue that in these two cases, the adult wizards simply don’t want Harry and the other kids to know what a Dementor is, since they’re such ghastly and dangerous creatures.

Then there are the operators of the Knight Bus, Stan and Ernie. Each of them says “Azkaban guards” while talking to each other about Black’s escape in Harry’s presence.

In this case, there’s absolutely no reason for these two characters to be using intentionally vague terms to shelter a kid they don’t even know. Perhaps Stan and Ernie are just too dense or ignorant to know what a Dementor really is, but I doubt it. They’re still adult wizards, after all.

The final two uses of “Azkaban guards” are the most unbelievable.

They’re both uttered by Arthur Weasley again, but this time he doesn’t know Harry is listening. This occurs in Chapter 4, just a few pages before Harry encounters a Dementor himself. Arthur and Molly Weasley are discussing Harry’s safety late at night while our young hero listens in undetected.

Even while talking to no one but his wife, Arthur still calls the Dementors “the Azkaban guards.”

There simply isn’t any way to make this make sense, unless that phrase is a commonly used alternative name for the Dementors within the wizarding world.

But the bulk of the novel that comes after Harry’s run-in with a Dementor proves that isn’t the case.

Adults in “The Prisoner of Azkaban” say the word “Dementor” a total of 50 times in Chapter 5 and beyond without ever calling them anything else. Dumbledore even calls them “The Dementors of Azkaban” rather than opting for “guards.”

Worst of all, Fudge himself, who already used the “guard” phrase earlier, goes on to say “Dementor” five times once Harry and the reader know what that is.

There’s no explanation for this about-face of phrasing other than the simple reason that the surprise for the audience has already been executed. And of course, the characters aren’t supposed to know about the audience.

Once you notice something like this and come to the conclusion that it only makes sense on the meta level, your sense of immersion in the story is bound to suffer.

Why it matters and how to fix it

Thus you have a classic case of “writing to the reader,” i.e. sacrificing the integrity of the fictional world in order to achieve some effect on the consumer in the real one.

This kind of literary mistake is especially common during the build-up to an important reveal or twist, because it’s easy to focus more on the audience impact than the continuity effects.

But it’s not exclusive to that scenario. Any flow of information that works from the audience’s perspective but not from inside the story itself is a case of writing to the reader in one way or another.

Maybe it’s not a mistake, you may be saying, but a calculated exchange. Why shouldn’t an author consider compromising a small amount of world coherence to set up a big moment that readers will remember?

My response: You can have your cake and eat it too, with a little work. Preserve the good, eliminate the not-so-good.

As I already mentioned, the Dementors play a crucial role in Harry’s development in this novel. They are the catalyst for our protagonist to start coming into his own, to put aside his fear and take control of his own power.

The climactic scene when Harry summons his full Patronus and defeats an entire horde of Dementors is immensely powerful and satisfying. I mean, what says “coming of age” more than being so heroic and awesome that your past self mistakes you for your dad?

That triumphant high point is built upon the rock of Harry’s fearful encounters with the Dementors throughout the story: they embarrass him in front of his friends, render him helpless during his beloved Quidditch, and reawaken traumatic memories of his parents’ final moments.

And yes, it all starts with that first encounter on the train, when Harry faints when no one else does, setting him on the path to fear fear itself even more than he fears Voldemort.

Teasing the existence of some nameless, shapeless horror in the first few chapters is an important part of the build-up, to be sure. We don’t want to take that all away and spoil the moment.

In addition, the shift in phrasing serves to solidify Remus Lupin’s introduction as a character.

The first thing Lupin does in this book series is banish a Dementor. The second thing he does is say the word “Dementor” in front of Harry for the first time.

Having Lupin be the one to finally call a Dementor by its real name is surprisingly effective. One of this character’s core traits is his genuine faith in his students. So of course Lupin would tell it to Harry straight when no one else had thus far.

It’s actually a neat way to show, rather than tell, who Lupin is as a person and a teacher. That’s certainly something we don’t want to undermine, either.

But there is a solution.

Let’s take every instance where a character says “Azkaban guards” and substitute “Dementors.” Add a line or two of dialogue where Harry asks what a Dementor is, and have the adults dodge the question.

Maybe the Knight Bus lines about the guards could be removed, but the Weasleys and Fudge could feasibly act evasive about the nature of Dementors when pressed by Harry.

Enter Lupin. In this edit, he may not be the first to say the word “Dementor,” but he could be the first to tell those students in the train car what the creatures actually are and what they do.

That way the setup and suspense over the “guards” can be maintained, and potentially even heightened, by hearing the interesting name “Dementor” a few chapters before the reader gets the answers. At the same time, Lupin gets to keep his neat introduction.

Was that so hard? If a nobody like me can think of a workable solution, I bet Rowling could have thought of a better one.

Unfortunately, she was writing to the reader.

Some disclaimers

If you made it all the way down here and you’re sharpening your pitchforks, please know that I love Harry Potter and I love “The Prisoner of Azkaban.” This issue is not a deal-breaker for the book.

It did dislodge my immersion considerably on my last reading, but it’s something most people probably won’t notice the first time around.

Call it a nitpick if you want, but examining these kinds of small storytelling wrinkles is something I wish was done in more detail more often. It’s a healthy endeavor when undertaken with the right mindset.

If you enjoyed reading about this concept of writing to the reader, let me know.

Tell me if you’d like to see me talk about other instances of this fallacy in entertainment media. Better yet, show me some of your own examples if you can think of any.

About the Creator

Caleb Daniel

You've read a million game, film, and book reviews that paint broad strokes as quickly as possible. I'm here to fill in the gaps, examining the specific good and bad traits of stories that too often go undiscussed.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.