The Paradox of the Production Code

Impossible Possibilities

My daydream is that I am a quick witted screenwriter in a 1940s Hollywood office with a clattering typewriter. I’m firing off one-liners, looking business like in my small hat, pencil skirt and fitted jacket. I smoke and drink whisky to be one of the boys.

I’m good at my job – my setups are sophisticated and my dialogue is sharp. And of course, I am always in a fight with studio bosses because:

“Rachel, you can’t say that.”

“But that’s what happens”

“It’ll never get past the censors.”

“I’m writing for audiences, not a bunch of suited bluenoses.”

“The bad girl doesn’t win.”

“In real life the bad girl always wins.”

“This isn’t real life. This is Hollywood.”

“I’m an artist. How can I work this way?”

“We didn’t employ an artist. We employed a hack – now get writing.”

Writing in the golden era of Hollywood meant adhering to the restrictions of the Production Code. The Code provided the movie industry ‘moral’ guidelines from 1934 to 1968.

Hey, Hollywood was wild: drugs, rape, murder. Scandal is good for short term gain, but surely you can’t build an industry on it.

And think of the children. Films are not just entertainment, not just business, they have the power to shape young minds.

There were three key principles to the code:

1. No picture should lower the moral standards of those who see it

2. Law, natural or divine, must not be belittled, ridiculed, nor must be a sentiment be created against it

3. As far as possible, life should not be misrepresented, at least not in such a way as to place in the mind of youth false values on life.

And then there is a proscribed list of things films can’t show, because movies could affect ‘spiritual or moral progress’ and the movies had a responsibility towards the masses who consumed them on a weekly basis. There were rules such as no sexy dancing, no nudity, no making fun of the clergy.

“Hey, studio boss, I’m a story-teller”

“Fair enough, just don’t tell this story.”

Parameters are good for creativity. “Just write anything”, never achieves as much as the sharpening tool of a word count, or a budget or a careful edit.

But rules also curtail.

Some lives literally become impossible. And the exuberance and energy of story-telling just, well, … disappears, like dust.

“Seriously, studio boss. What’s your problem? They’re married.”

“They don’t need a double bed to tell us that. Besides, we can’t sell it to the Brits unless it is twin beds.”

So, bedroom talk, a place of secrets and seduction was impossible.

“She’s a mother, already.”

“They don’t need to see her pregnant belly. I mean it will fly in New York, but not in Pennsylvania.”

Literal life-giving was an impossible life.

“But they’re in love”

“Not with each other.”

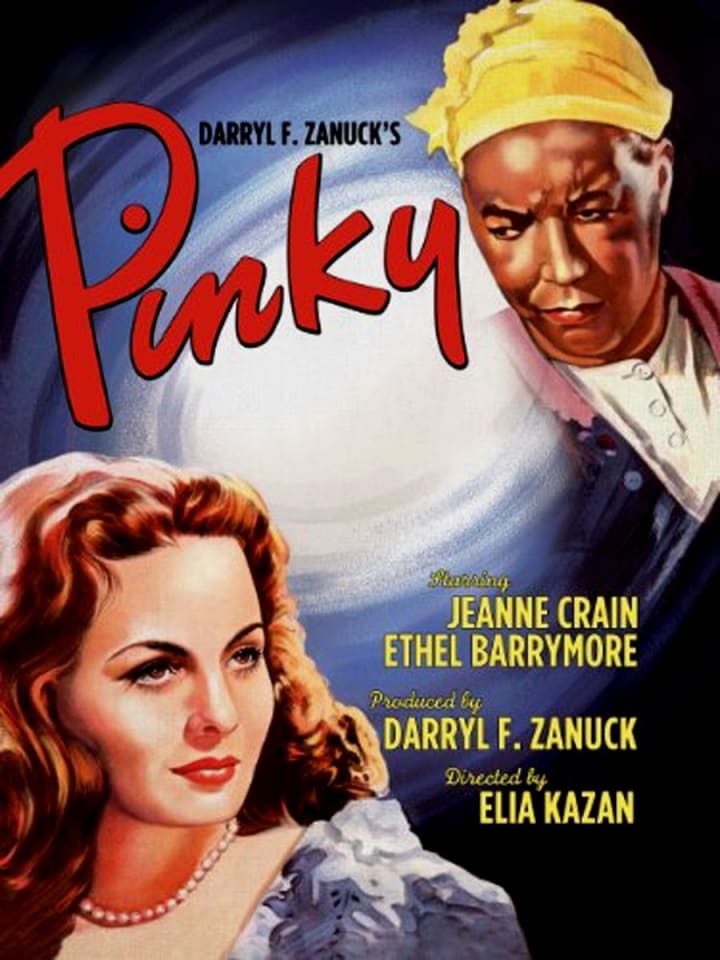

What happened when the moral arbiters were immoral? When they were racists or homophobes? Gay love became an un-screenable perversion. Racial harmony became a threat. Lives were lived on the edge of visibility.

Sometimes, this made great art, the circumnavigation of rules became inventive. But sometimes lives just disappeared: the feisty lives, the marginalised lives, the radical lives, the complicated lives.

1940’s screen-writing Rachel is hard-bitten. She remembers a just-passed time before the censors took charge and women took lovers, had children out of wedlock, got rid of cheating husbands one way or another and felt no need to remarry. She remembers women having fun and getting away with it. She remembers them as fiery, ambitious, sexually ambiguous, playing with identity. And she knows that was why the code was invented: to curb her freedom and to make her characters cry in misery and depend on men.

Screen-writing Rachel remembers the early 1930’s. She had been brought up to see the close up face on the screen and know that there was a way to live a life that confounded stereotypes and that complicated women could dominate the box office.

“Hey, you bossy broad. Just lighten up and write me a hit.”

Of course, Mr Studio Boss didn’t see a problem with writing under the Code. He was a man with hands that liked to roam and films that made money.

So screen-writer Rachel might not be able to make the bad girls win, but she sure as heck can give them the best lines.

“I need this studio boss, like an axe needs a turkey.”

And when he’s lying face down in my pool, I’ll be ready for my close up.

About the Creator

Rachel Robbins

Writer-Performer based in the North of England. A joyous, flawed mess.

Please read my stories and enjoy. And if you can, please leave a tip. Money raised will be used towards funding a one-woman story-telling, comedy show.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insights

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Excellent storytelling

Original narrative & well developed characters

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments (4)

Us men have a lot to answer for.

The early days of Hollywood were a mixed bag of Good and Bad. Pre Code let them tell the stories they wanted to, and explore many different techniques and ways to tell a story, While the Code limited what they could overtly show or tell, they found ways to get past the censors. We all know Lucy and Desi were married, and obviously fooled around, But they had two single beds, on the tv set. It wasn't until the mid-seventies, that married couples got the same bed, on screen. I also have vivid memories of seeing the Jane Russell Cross Your Heart bra, ads on tv, with her wearing the bra over a sweater. Today they show everything in living color..

I like the personalized inserts and the lesson in filmography.

Oh this is wonderful. I quite like 1940s screenwriter Rachel! I feel like you'd be slipping in some grand stuff past the censors.