The Danger of Nature in Mary Shelley's “Frankenstein”

An Essay

Written and revised by Mary Shelley, “Frankenstein” has since become one of the most adapted and best-selling gothic novels of all time. Focusing on the studies of anatomy by Victor Frankenstein, it details his creation of a living monster. Victor later loses the monster and goes mad looking for him in dangerous conditions that often threaten the lives of those nearest and dearest to him. Apart from the deaths of physical people, nature presents something threatening to Victor as well. As a scientist, he must be reasonable - echoing back to the age Mary Shelley was born just after, the Age of Reason. But, Victor proves to be a romantic when it comes to his discussions of the sublime aspects of the natural landscape and therefore echoes the modern period in which Mary Shelley herself is thriving - the Romantic Age. Nature is often presented as something not just threatening, but something that is directly dangerous to either the physical or psychological being of the protagonist/narrator at the time. Through science, it is often presented as the subject that should be left alone to flourish rather than bent to one’s own will. Victor Frankenstein, learning this the hard way, will pay the ultimate price for attempting the bend nature and play God. The human condition cannot flourish and cannot thrive in an atmosphere and scene that is filled with creations that are known to be against nature and thus, things in the Monster’s path die out or become damaged.

The “seat of frost and desolation” is more than often discussed as one of the foremost powerful statements about nature in the ‘Letters’ section of “Frankenstein”. As Robert Walton writes to his sister, he discusses his voyage to the “seat of frost and desolation” in which the extreme cold is used alongside a word which is often used to describe destructive atmospheres. Thus, we get this immediate and somewhat unsettling aspect of nature before we have discovered the main storyline of the novel. It is actually Robert Walton who encounters dangerous weather and does not try to work against it. In the fourth letter he observes: “Our situation was somewhat dangerous, especially as we were compassed round by a very thick fog.” This being said, he immediately follows that statement with a want for the fog to lift and the ice to melt, but makes no attempt to set nature against him as he has done for the previous three letters. Walton has, in a reader’s eyes, learnt his lesson about encountering the dangers of upsetting nature in voyaging to a place no man was meant to go. Victor Frankenstein will do the same thing in his research of the natural form of man, taking on the aspect of playing God and eventually voyaging in this research to a place no man was meant to go. Robert Walton’s travels are but just a meek foreshadowing of what is to follow. It is this narrative though that sets out the very idea that working against nature can incur the wrath of its higher powers. An idea most explored by the sublime.

Victor Frankenstein’s own narrative shows us that when Victor has these dreams of humans not dying from disease but only from some ‘violent death’ - he begins his play with the natural world and the natural world strikes back against him in the consecutive paragraph:

“When I was about fifteen years old we had retired to our house near Belrive, when we witnessed a most violent and terrible thunderstorm. It advanced from behind the mountains of Jura, and the thunder burst at once with frightful loudness from various quarters of the heavens. I remained, while the storm lasted, watching its progress with curiosity and delight.”

The advance of the thunderstorm leaves Victor in shock at its progression towards him and thus, he begins to think of nature as something both to be dwelt upon and delighted by, and also to be terrified by but still dwelt upon. The way in which nature deals with its wrongdoers is simply right in front of him and he still cannot see the vast amounts of danger, he takes it not as a warning but a chance to glance even further into the concept he has thought of:

“As I stood at the door, on a sudden I beheld a stream of fire issue from an old and beautiful oak which stood about twenty yards from our house; and so soon as the dazzling light vanished, the oak had disappeared, and nothing remained but a blasted stump.”

He watches the oak tree become destroyed and speaks to himself about the laws of electricity and how he observes their destruction through the thunderstorm. Of course, in hindsight, Victor knows that whatever he is planning to do next could be thought of obsessive, immersive and yet, still so very wrong:

“…the last effort made by the spirit of preservation to avert the storm that was even then hanging in the stars and ready to envelop me.”

It is not until Chapter 4 that we see that natural philosophy and the concept of nature itself has seemingly taken over Victor Frankenstein’s entire being. This is where we get Frankenstein obsessed with not just nature in terms of the weather and the outside world, but also with the aspect of human nature, animal nature and the laws of nature that govern the everyday life of the living being:

“One of the phenomena which had peculiarly attracted my attention was the structure of the human frame, and, indeed, any animal endued with life.”

It is this that foreshadows the obsession which comes forth in later chapters when Frankenstein attempts to create what we come to know as The Monster. He becomes not only obsessed with the idea of creating the animate nature of a living being but figures out that he must, in fact, work backwards. The dangers of death are held suspect in this world which is still governed by some religious laws preventing the studies of death including but not limited to: autopsy, dissection and, the one that Victor Frankenstein actually performs - grave robbing:

“To examine the causes of life, we must first have recourse to death. I became acquainted with the science of anatomy, but this was not sufficient; I must also observe the natural decay and corruption of the human body.”

Again, in hindsight, Victor Frankenstein observes for himself that his own ‘nature’ as a man could not and should not allow him to become this ‘great’ with his own powers over the natural laws of the world - those mostly of life and death:

“Learn from me, if not by my precepts, at least by my example, how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow.”

It is this that we see that leads him towards the main plot of the narrative in which he actually creates the Monster in which “..life and death appeared to [him] ideal bounds…” and thus, he himself creates his own downfall through the very Shakespearean flaw of ambition.

The pathetic fallacy of his realisation of obsession and the beginning of the journey towards the creation of the Monster is one that is dull and foreshadows an obvious sense of darkness:

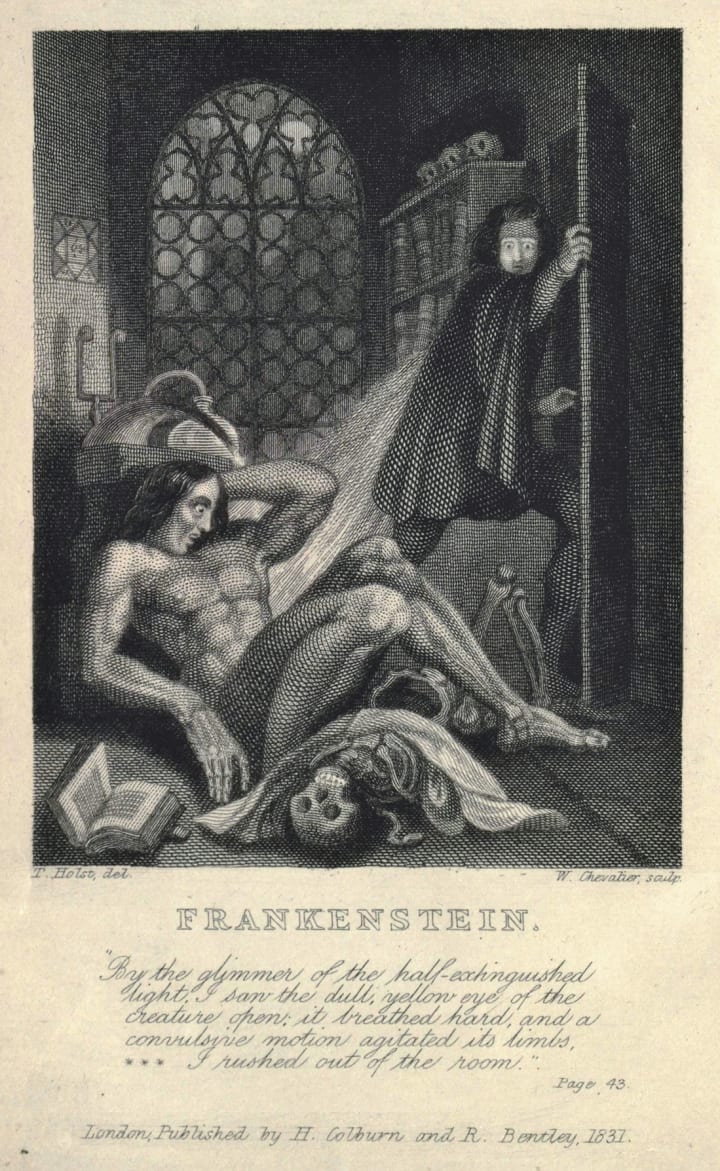

"It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils.”

As we know that Victor Frankenstein is recounting this, we should also remember that adjectives such as ‘dreary’ in order to create atmosphere are added in afterwards and therefore are biased towards the opinion of the narrator upon the task that is being carried out. In this case, creating an animate being which will lead to tragedy and death. It is only when the Monster is brought to life that Victor realises that the laws of nature cannot bend to his will and that he may have actually made one horrifying and terrible mistake that will cost him dearly:

"The different accidents of life are not so changeable as the feelings of human nature. I had worked hard for nearly two years, for the sole purpose of infusing life into an inanimate body. For this I had deprived myself of rest and health. I had desired it with an ardour that far exceeded moderation; but now that I had finished, the beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart.”

The dangers of nature are also off-set against Victor Frankenstein’s own ‘painful’ emotions and though he is not able to bend them to his will, they are more than able to do the same to him instead. He describes in his return to Geneva upon the death of his younger brother, William, that he stops by ‘calm waters’ on the way:

“I remained two days at Lausanne, in this painful state of mind. I contemplated the lake: the waters were placid; all around was calm; and the snowy mountains, “the palaces of nature,” were not changed. By degrees the calm and heavenly scene restored me, and I continued my journey towards Geneva.”

As he states, ‘by degrees the calm and heavenly scene restored me…’ he does not himself recognise the irony in comparison to the chapters before when he himself has been obsessed with the changing nature of weather and atmosphere, the very laws of life and death itself and the philosophies of the animate being to the point that he has attempted to govern them for his own pleasure. He only seems to recognise the horror that it would project back on to him, but not the way in which nature would turn the tide and replace his own emotions with its strong pathetic fallacies.

It is when Victor Frankenstein arrives back in Geneva that he begins to recognise the weather changing in order to warn him of the dangers that are still to come and yet, he takes it as the danger that has already passed:

“During this short voyage I saw the lightning playing on the summit of Mont Blanc in the most beautiful figures. The storm appeared to approach rapidly, and, on landing, I ascended a low hill, that I might observe its progress. It advanced; the heavens were clouded, and I soon felt the rain coming slowly in large drops, but its violence quickly increased.”

The idea that the violence increases comes from the very fact that the Monster is on the move and though Frankenstein knows this, it could be an act of self-denial. He is denying himself the right to state that he was not only wrong but he was the one to blame for his brother’s death (his brother being killed by Frankenstein’s Monster). The reader sees this far more clearly in the following paragraphs when the storm picks up and Victor Frankenstein seems to lose his reasoning in favour for the overwhelming nature of the sublime:

“While I watched the tempest, so beautiful yet terrific, I wandered on with a hasty step. This noble war in the sky elevated my spirits; I clasped my hands, and exclaimed aloud, “William, dear angel! this is thy funeral, this thy dirge!”…”

This is in a direct contrast to anything that happens regarding the Monster’s narrative. As Victor discovers the true power of nature through the fact that he tries to overpower it to little avail whereas, the Monster at the same time is learning about the true power of nature through the raw experience of its brilliance. This is why the Monster tends to have less guilt within him even though some horrid crimes are committed. Most of the guilt comes in the form of Victor’s second narrative in which he wholeheartedly regrets creating the Monster and that is because the Monster represents the very cause of Victor’s want to be more powerful than nature - it represents his will to be a God over a man.

In Chapter 11, the sensation of discovery for the Monster that he explains to Victor Frankenstein is filled with interest and a sort of respect for the power of nature. This is directly opposite to the fact that Victor Frankenstein demonstrates his interest but with a power of little respect for nature or, later on, natural philosophies. From the Monster, we can see that even something as basic as night and day can fascinate, excite and confound every sense:

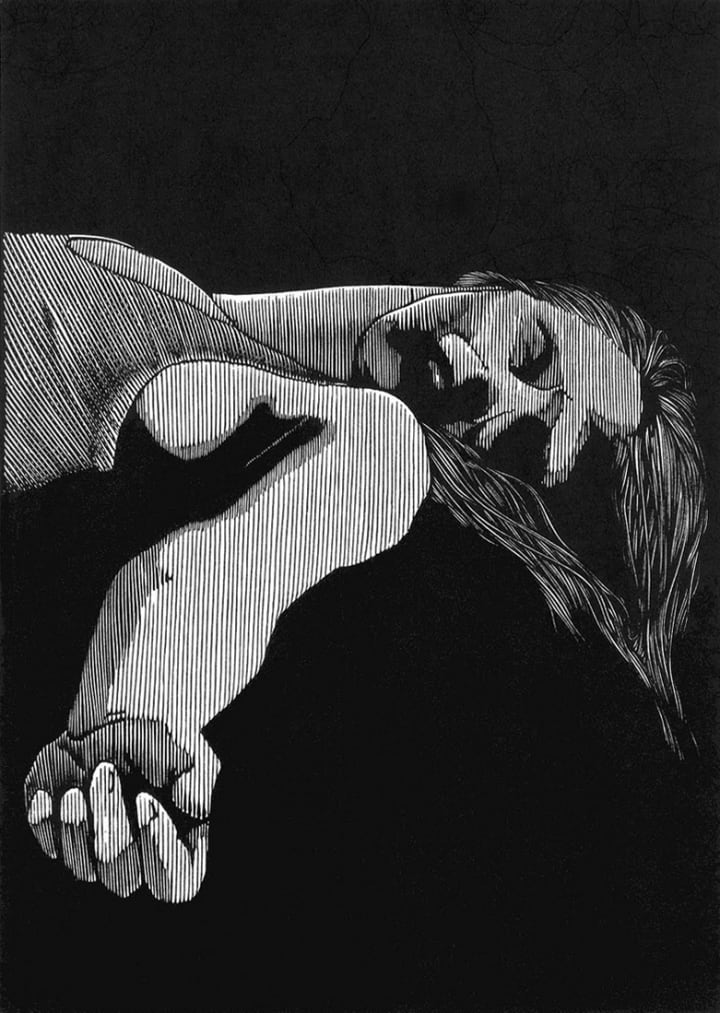

“Darkness then came over me and troubled me, but hardly had I felt this when, by opening my eyes, as I now suppose, the light poured in upon me again. I walked and, I believe, descended, but I presently found a great alteration in my sensations. Before, dark and opaque bodies had surrounded me, impervious to my touch or sight; but I now found that I could wander on at liberty, with no obstacles which I could not either surmount or avoid. The light became more and more oppressive to me, and the heat wearying me as I walked, I sought a place where I could receive shade.”

Every sensation of nature is filled with this awe that is represented by the Monster experiencing everything for the first time on his own. This seems to confuse the Monster but there is never a want to excel past it. There is a want, rather, to learn and take it in, to understand and to realise what the greats of nature are:

“Soon a gentle light stole over the heavens and gave me a sensation of pleasure. I started up and beheld a radiant form rise from among the trees. [The moon] I gazed with a kind of wonder.”

A word that is repeated by the Monster whilst observing things that are sublime and overwhelming in nature and appreciating them in order to understand further is ‘pleasure’. This is something that, by Victor Frankenstein, is not intended for use very often and especially not in the context of realisations of the greatness of nature. This is why Victor Frankenstein himself, especially when alone, seems to experience the dangers of nature rather than the pleasures. It is like nature goes to get its revenge on Victor Frankenstein whilst also creating a dual path for the Monster through pleasure and pain. The Monster is not punished by nature as he is only a creation, it is the creator who is punished through his lack of appreciation for the realities of the world as they are.

The pain that the Monster experiences of nature is seen in the form of learning about fire. The Monster observes that fire gives of heat and is therefore, good. But, the danger is created when the Monster tries to touch the fire. He realises its power and does not repeat the action:

“One day, when I was oppressed by cold, I found a fire which had been left by some wandering beggars, and was overcome with delight at the warmth I experienced from it. In my joy I thrust my hand into the live embers, but quickly drew it out again with a cry of pain. How strange, I thought, that the same cause should produce such opposite effects!”

He proceeds to learn about how to create fire. Instead of Victor Frankenstein’s ideas to overcome the philosophies and laws of nature, the Monster seeks out an understanding of how to create them anew and produce them to help his existence. This is another reason why nature does not take out its vengeance against the Monster. It is only when Victor’s second narrative arises do we learn why the Monster is not actually blamed for the crimes he commits. The Monster states it himself saying: "I am malicious because I am miserable.” The Monster is alone and therefore, socially he is miserable. He asks Victor to create another like him but Victor, now realising what he has created - refuses.

In his second narrative, Victor Frankenstein attempts to recreate the life he had before the Monster was made and yet, he is forever cursed not just by the thought of his creation - but the thought that his creation had went so well in terms of copying human behaviour that now, it required someone to be a part of its life. He conceals his truths when speaking with his close friend Clerval which he describes in his second narrative in a form of foreboding as a man he is overjoyed to see that he is alive to ‘every joy of life’:

“I was occupied by gloomy thoughts and neither saw the descent of the evening star nor the golden sunrise reflected in the Rhine. And you, my friend, would be far more amused with the journal of Clerval, who observed the scenery with an eye of feeling and delight, than in listening to my reflections. I, a miserable wretch, haunted by a curse that shut up every avenue to enjoyment.”

The dangers of nature are now pursuing Victor with a great force as now, it is not like his first narrative in which storms and glaciers overwhelm his thoughts and being. Instead, it is the path which he has chosen to overcome nature and its laws, that comes back to haunt him. It is the danger of not creating another being and therefore being threatened by his own creation and paradoxically creating another being and therefore putting many other people, including himself and Elizabeth, in great danger.

When we approach the ending to the narrative, we get this unlocking of nature. After all the tragedy has occurred, we are drawn all the way back to Robert Walton’s letters in which he has unhinged the ship from the ice and is now on his way home. The ice splitting in one of the final letters Walton writes to his sister is almost symbolic of the laws of nature splitting open and showing Victor the very depths of his illness - an illness that Robert Walton states that Victor cannot fight for too long. But, by the very end of his life - Victor Frankenstein still has not learned his lesson from nature and wishes death upon the Monster he has created, though he cannot create it himself as he did with the Monster’s life. This is the one aspect of life Victor Frankenstein could never overcome and though he fails to admit it, he understands it perfectly: it is death.

The Monster admits he has killed, but is remorseful for it. Frankenstein does not admit that it is his creation of the creature that inadvertently caused the deaths of all of these people. The Monster realised far before Frankenstein that he has no power over life and death and therefore, must wait for nature to push its vengeance unto him:

“I look on the hands which executed the deed; I think on the heart in which the imagination of it was conceived and long for the moment when these hands will meet my eyes, when that imagination will haunt my thoughts no more.”

Symbolically the Monster will die in the dangers of nature from whence it was scared and realised the dangers that nature could enforce against living beings. The Monster itself is a creation that is dangerous to all living things and therefore, he feels he must die in a funeral pyre fire. A fire that is dangerous, as he has realised before, as he realises that he is as well.

In conclusion, the Monster and Victor Frankenstein give the reader a number of dangers to examine but the only one who succeeds in analysing himself against them is the Monster. The fascination and exploration of each aspect of nature is all well and good, but when one tries to surpass this, as Victor did and the Monster did not, they will suffer and bring suffering down upon everyone else.

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

200K+ Reads on Vocal.

English Lecturer

🎓Literature & Writing (B.A)

🎓Film & Writing (M.A)

🎓Secondary English Education (PgDipEd) (QTS)

📍Birmingham, UK

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.