How Nashville captured the turbulence of 1970s America

Forty-five years ago, Robert Altman offered a vision of the US centred on the home of country music. It’s a tale of disorder and denial still relevant now

Nashville, Tennessee is a storied city. It’s home to the Grand Ole Opry, the major ‘you’ve made it, kid’ live venue for country stars, and is widely thought of as the major incubator of country music in the United States. It was 45 years ago when Robert Altman and screenwriter Joan Tewkesbury cast their eye on the city as a backdrop to their 1975 film of the same name. Within an expansive near three-hour running time, they combined a realistic – if heightened – vision of the country music capital with their thoughts on a turbulent political era in the US, sewing their impressions of the star-spangled, hairsprayed, patriotic heartland into a ragged tapestry, and one that was beginning to fray at its edges.

Nashville takes place over the course of three days, as a populist third-party presidential candidate – Hal Phillip Walker – hires musicians to perform at one of his political fundraisers. With a meaningless platform including ideas like changing the national anthem to be simpler, Walker’s campaign doesn’t occupy one side or another so much as it is a glorious sham. We never actually see Walker himself, but instead his employees and fixers; his campaign seems entirely represented by a van with a logo and a loudspeaker, driving around the city blaring out slogans and facile talking points.

Altman’s film zones in on some two dozen characters over its duration, each occupying a different stratum of the country music scene in the city. At the top of the pile is Barbara Jean (Ronee Blakley), a gentle star suffering from chronic illness, dressed often in flowing whites like a Victorian doll. Haven Hamilton (Henry Gibson) is the patrician veteran of the scene, a platinum recording artist with a host of obnoxiously sentimental tunes about the US (“We must be doin’ somethin’ right / To last 200 years”). Then there’s Keith Carradine as Tom Frank, part of a popular folk trio on the more bohemian side of things. He’s a callous womaniser, and although his group is ostensibly a part of the counterculture, they ultimately prove to be as shallow as the rest. Meanwhile, Albuquerque (Barbara Harris) and memorably bad singer Sueleen (Gwen Welles) are desperately chasing stardom, even while clearly being ill-equipped for it. In telling his story of the US, Altman both deploys and subverts one of the country’s foundational cultural clichés – the unknown hopping on a bus and finding riches and fame, the countrified Horatio Alger story.

A mosaic of music and politics

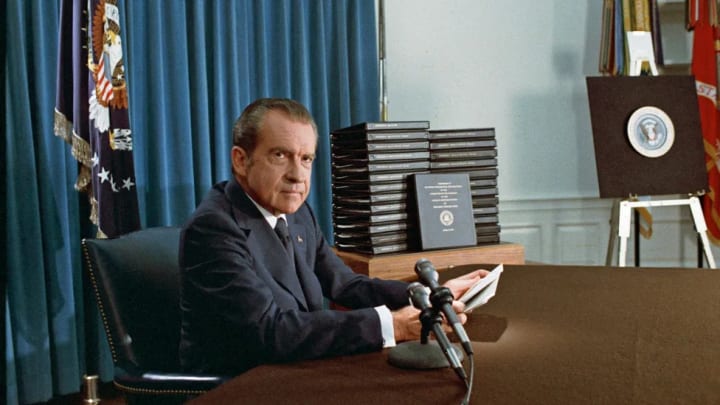

Beginning with a series of fender-benders on the highway outside the city, it develops into a mosaic of stories that capture the surreal and swinging circus of contemporary American life. Amid the good ol’ boys and the connivers, Altman offered an unflinching vision of a nation that had just come through the throes of the Watergate scandal, in which a president who had won by a landslide in the last election was revealed as a crook.

It’s funny how pointed Nashville’s linking of celebrity culture to politicking would become; in less than a decade, movie star cowboy Ronald Reagan would be president

In Nashville’s world, the rules of the game, whether in music or politics, are the same: we see the cheerful ignorance of a group of people who are largely exposed as shallow and morally small, their jockeying for position and power, and use of mawkish sentiment and careworn family values to sell things to a willing public. It’s funny to see how pointed Nashville’s linking of celebrity culture to politicking would become; in less than a decade, movie star cowboy Ronald Reagan would be president. Just like the country’s favourite crooners, presidential hopefuls from both sides of the aisle would call on good old fashioned values of God, country, and looking out for the little folk for years to come, from the fuss made by Jimmy Carter over his former days as a peanut farmer to George W Bush’s down-home Texan routine.

But although many of Altman’s characters are the targets of jaggedly funny satire – not least the insufferable British BBC Radio journalist played by Geraldine Chaplin – there is generosity there, too. From a distant medium shot, he shows the otherwise obnoxious Delbert Reese (Ned Beatty), a lawyer who is one of Walker’s local campaigners, in a quiet moment as he fries eggs, suspecting his wife is having an affair; the cheating woman, played by Lily Tomlin, is a sad and kind housewife with two deaf sons that she dotes on. The Nashville community may not have loved Altman’s pointed depiction of them, but he was never a filmmaker who denied the inexorable, basic humanity of his characters.

At the same time, Altman makes the detail-specific, the incidental, and the intimate seem profound. Nashville transcends its environment even as it captures it so closely; it tells a story about the bitter end road of aspiration, the uselessness of celebrity, and the flagrant stupidity of a political system that increasingly resembles that same celebrity culture.

An indelible ending

That there is also shown to be underlying violence in that system is unsurprising – at Nashville’s climax, a gunman opens fire at the Walker fundraising concert, shooting an innocent Barbara Jean down on the stage in front of an audience. Cinema and political assassinations became curiously intertwined in the 1970s and early 1980s, from movies that inspired assassination attempts (Taxi Driver) to assassinations that inspired movies (The Parallax View).

In the indelible conclusion of the film, Barbara Harris provides a haunting, soulful rendition of a song, It Don’t Worry Me, to soothe the chaotic audience after Barbara Jean is rushed to hospital and the gunman is apprehended. They soon join along with her anthem, a pliant croon of reassurance and repetition that seems to comfort the shell-shocked observers. Cinematographer Paul Lohmann’s camera jumps between individuals, mostly corn-fed white faces – a real-life audience serving as extras, so the apocryphal story goes.

With the deep sentimentality of its songs and the lacquered hair of its gussied-up stars, Nashville was perfectly reflective of its time and place. In the mid-1970s, there was a well-established resurgence of country music in the US. The genre spoke to tradition and old-school Americana; it was the white heartland’s way of pretending that social turbulence, anti-war protests, and presidential corruption were far from their own reality. With very few exceptions – Kris Kristofferson chief among them – the country artists of the era proffered a myopic view of their nation aimed at Nixon’s so-called ‘silent majority’ – the term the President coined in 1969 to refer to those Americans who were poles apart from the new counterculture.

The easy-going verses of It Don’t Worry Me are a catchy ode to cheerful ignorance, after all: “You may say that I ain’t free / But it don’t worry me”. Look at the Southern rock group Lynyrd Skynyrd’s similar admission of indifference a year before – “Watergate, it don’t bother me” they sang in their 1974 anthem Sweet Home Alabama. Altman and Tewksbury do well to remind us that embracing a complicated political reality is not of interest here – a collective denial, some would argue, that continues in the US to this day.

Altman’s peculiar cinematic juggernaut is a grand, empty, ugly emblem of national pride – of politics as entertainment, and of the business of complacency and distraction. Nashville strikes right down to the heart of American life, to its pomposity, and, abidingly, its dubious, paper-over-the-cracks optimism in the face of genuine violence and terror. During a global pandemic and a fraught election season, its despair feels as sharp as ever.

About the Creator

Sue Torres

Is there any other reason to live to change the world?

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.