Hope without guarantees - the life and works of J.R.R Tolkien

A look at the depth, wisdom and influence of the 'Legendarium' of J. R. R. Tolkien: father of high fantasy, smoker of pipes and god of nerds.

Mae govannen!

If we were to meet one day, dear reader, perhaps crossing paths in London under a gently insinuating, but probably over-priced, rain shower, I would begin our discourse with the phrase, 'Mae Govannen' (well met!) before we began expounding on the recent sports-ball tournament, our writing projects, the depressing news tales, or more likely, our cats. It being London, we would likely be shoved in front of a passing bus by one of the friendly locals, and therefore it might be safer if we tried convening in a pub.

If we met under more auspicious circumstances, say a book-launch, a date, or a black-tie cocktail party to celebrate the smiting of an enemy, you might experience me with my arms outstretched, a big grin on my face, declaring, 'Elen síla lúmenn’ omentielvo' (A star shines on the hour of our meeting) before you embarrassedly checked your watch, said 'oh...is that the time?...I have a thing in the morning...' and rightfully left me standing there on my own, a solitary black-tied figure at Smite-Fest 2022.

NB: If we ever do go on a date and I say that, you have my permission to cast me into the fiery cracks of doom. Oh gods, that sounds like a euphemism...it's not, honestly... no please don't scream, it's a refere-)

(look for this sign if someone speaks Elvish on a first date, unless you're into it.)

In either of these, dare I say, enticing hypotheses, once the talk turned to books, you could be guaranteed that apart from one of the benchers on my ever-engorging TBR pile, I'm guaranteed to be currently plunging my ink-stained nose into one of the Legendarium, the series of books and writings from the father of high fantasy himself, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, J.R.R Tolkien, JRRT, or, as I hear tell in youth parlance, 'Jurt'*.

*I made this up, this is not a thing.

In this short* monograph, I aim to explain why, to me, Professor Tolkien is not only the creator of the greatest fantasy world in literature, but also, in many ways, the originator of all modern fantasy literature. I will explore how his early life shaped the themes of his writing, explain why he means so much to me, and elucidate on how the fandom from his works has become very dear to my heart.

*not a guarantee

But first, the author himself. Where possible, I will put anything that relates to the Legendarium in bold. I will focus on his young life for the most part here, as it ties in with the themes that appeal to me so much.

Tolkien's Young Life (please bear with me, this is long!)

Rural Idyll

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien CBE FRSL (1892-1973) was born in what is now the Free State Province of South Africa. Whilst holidaying in England at the age of three, Tolkien's father died, and his mother, Mabel, decided to stay, raising John Ronald, and younger brother Hilary, in Sarehole Mill (now lovingly referred to as 'Arsehole Mill'), an idyllic Worcestershire rural village (pronounced 'Wooster-shirr') where the boys were free to roam the nearby hills and woods, and visit their Aunt Jane's farm, Bag End. Sarehole Mill fell victim of urban creep, and as Tolkien grew up, his beloved rural idyll was becoming a place of smoke...and machines and wheels.

(Aunt Jane's farm?)

Following financial abandonment by her staunchly Protestant family for converting to Catholicism (#familyvalues) the Tolkien's moved to Birmingham. Mabel home-schooled the boys, inculcating a love of languages, natural philosophy and mythology. John Ronald revelled in the Norse tales of fierce monsters and stoic heroes, in the Norman/Welsh tales of the Arthurian Knights, adoring their nobility of chivalry and knighthood. Sadly, Mabel died of acute diabetes, 10 years before the discovery of insulin, and so John Ronald, twelve years old, was taken under the guardianship of a Catholic priest, Father Francis, and sent to live in lodgings with his brother.

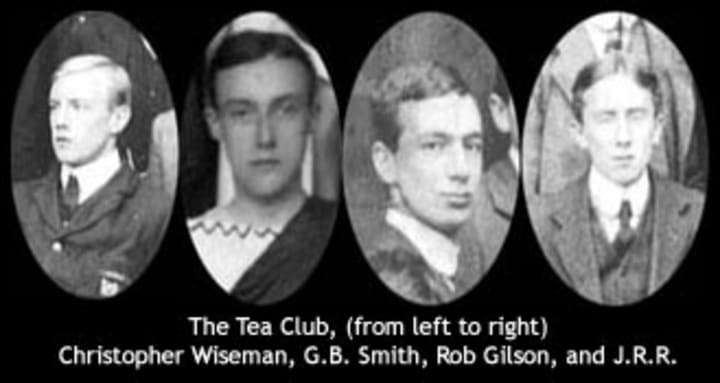

Four Friends

Attending the King Edward's School in Birmingham, a school noted for producing linguists, John Ronald made friends with a group of like-minded young idealists. His closest friends were Christopher Wiseman, Rob Gilson and Geoffrey Bache Smith. Together they were the core of the Tea Club and Barrovian Society, TCBS for short, a teenage Bloomsbury Group who met in Barrow’s Stores, discussing their artistic endeavours and their hopes for changing the world. These four friends became as close as brothers, and would meet up for what remained of their lives.

Lúthien

As a teenager, Tolkien met Edith Bratt, a fellow lodger and orphan, and instantly fell in love. This love consumed him, and their beautiful relationship influenced his writing in the most profound sense. As he was studying for a scholarship to Oxford at the time, Father Francis forbade young Tolkien from courting his darling (Protestant, older) Edith, until he was emancipated from guardianship, and so they parted...until the evening of his 21st birthday, when Tolkien promptly wrote to her. Learning she had accepted the proposal of another man, he visited her, talked to her, and they became engaged. One clear memory of Edith was a time when, in 1917, she danced for him in a hemlock grove, a beautiful example of their need for solitude together in nature, and the secret world of their own love. Tolkien's letter to his son, following her death in 1971, recalled:

“In those days her hair was raven, her skin clear, her eyes brighter than you have seen them, and she could sing – and dance...For ever (especially when alone) we still met in the woodland glade, and went hand in hand many times to escape the shadow of imminent death before our last parting. ” (Tolkien letter 340 to his son, Christopher, in 1972.)

Their love story is both a source of romance and hope for me, and also gives us this beautifully cringey moment in the film 'Tolkien', where he repeats the word 'Selador' a thousand times whilst on a date (although she seems into it). This is actually quite accurate. By the age of 17, Tolkien had composed his first language, and Edith was always a firm supporter of his creations.

War

Tolkien won his place to Oxford, and graduated with first class honours. Whilst a student, the tensions that had embroiled Europe broke out into what became the First World War (1914-18), and undergraduate students, the 'officer class', volunteered in droves, and were killed in droves. Tolkien finished his degree, appalling friends and relatives who thought it absurd, even cowardly, that he should delay his enlistment until he had graduated. He completed his final examinations, and was almost immediately commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers. During training, he finally married his Edith, and a few weeks after their wedding, he received orders to report to take ship to France. The life-expectancy of junior officers could be measured in hours at the front, and so for the young couple, his summons to war was a death sentence.

Tolkien was not a natural officer. Though gallant, and concerned with the welfare of the working class men under his command, he lamented the military requirement for power and dominance over others, stating that,

"The most improper job of any man ... is bossing other men. Not one in a million is fit for it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity." (Garth, (2003). Tolkien and the Great War.)

Arriving in the opening days of the Battle of the Somme (1916), Tolkien saw first-hand what the mechanised nature of modern warfare had reduced mankind to. As he led small detachments through the sodden, swampy fields of the dead in futile, impersonal slaughter, his ideals of chivalry, warfare and honour were quickly pulverised. Poison gas, barbed wire, indiscriminate shelling and the machine gun, coupled with the military strategy de jour of calmly walking towards the enemy led to his regiment being nearly completely wiped out.

Around this time, he began writing little snatches of imagined history and language in his notebook, sketching the languages and histories that became the framework for Middle-Earth.

Recovery and Later Life

Tolkien was invalidated out of active service by November 1916, a victim of trench fever that came with the incessant lice that feasted on soldiers at the front. Of his four closest friends in the nine-member TCBS, by 1918 all but one of them, Christopher Wiseman, had died in battle. Tolkien and Wiseman remained friends, although they were never as close as they had once been, an understandable consequence of the devastation that war wrought upon them. (Tolkien nonetheless named his third son Christopher.)

Tolkien's life had changed irrevocably. He returned broken, traumatised and disillusioned. His wartime notebook led him to begin 'The Book of Lost Tales', which in time, laid the foundations for the world of Middle Earth.

Edith's love restored him, and he carried on with life, eventually becoming a contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary, a professor of English language and philology, a World War Two codebreaker, and most-famously, the author of the Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion. He died, a hugely successful author, in 1973, mere months after the passing of his beloved Edith.

So why does this help prove that Tolkien created the greatest fantasy world?

Tolkien himself was wary of biographers trying to piece together 'where a writer's work comes from' by reference to their lives, but in his own words:

"An author cannot of course remain wholly unaffected by his experience, but the ways in which a story-germ uses the soil of experience are extremely complex, and attempts to define the process are at best guesses." (JRRT, Foreword to the Second Edition of Lord of the Rings 1966)

Although this anti-allegory stance may seem to render my words above pointless, I believe that a brief look at his life points us to some of the key reasons why he is Chief of the fantasy writers. Namely the depth of his world-building, the themes that he explores, the values that he champions and the universal applicability of his work.

Why he is the best.

1: World-Building, Linguistic Foundations and History.

Tolkien was a philologist, historian and linguist, studying the history of languages, primarily the many languages that became English, such as Angl0 Saxon and the Germanic languages. His undying passions, were mythology, history and language. Having been taught Latin, French and German from his mother, he went on to become fluent, conversant or academically familiar with the following languages:

(To the tune of The Major-Generals Song by Gilbert and Sullivan - ALTOGETHER NOW)

He knew (inhale:)

English, German, Spanish, Latin, French, Old-English, Esperanto/ Russian, Finnish, Welsh, Norwegian, Middle-English, Old Icelandic/ Old Norse, Gothic Language, Dutch, Greek, Danish....

You get the idea.

Language, to Tolkien, was a living historical document, one that acts as the skeleton to a culture. A knowledge of the philological and linguistic history of a culture can act as a guide through its physical history, its artistic expression, its movement and 'shape'. In this capacity, when creating the world of Middle Earth, his primary motive was two-fold: to write for his own pleasure and to engage with his passion,

"I wished first to complete and set in order the mythology and legends of the Elder Days... I desired to do this for my own satisfaction, and I had little hope that other people would be interested in this work, especially since it was primarily linguistic in inspiration and was begun in order to provide the necessary background of 'history' for Elvish tongues' (JRRT, Foreword to the Second Edition of Lord of the Rings 1966)

THAT alone to me is worthy of him being granted the title of 'Best' in terms of creating a fantasy world. He had begun creating languages from his passion for philology. With the Elven languages, for example, with their influences in Welsh and Finnish, the language of the Rohirrim, the Horse warriors of Rohan, with their Anglo-Saxon influences etc. Tolkien created the languages first, and then allowed the myths and history to fall into place.

Not only did he create whole languages, modes of writing, mythologies and histories, but our boy Jurt (sorry):

CREATED A GODDAMN CREATION MYTH.

In all fantasy writing before the publication of the Legendarium, there had never been a more fully developed world in which the characters belonged. Since the publication of his works, this model has been used, to a greater or lesser extent, by virtually all fantasy fiction writers.

2. Themes of the Legendarium

The thematic depth of Tolkien's writing has spawned nearly as much academic and fan-based speculation and discussion as its linguistic basis. Two themes that I will explore more fully are those of Hope, and of Love. There are hundred of themes in Tolkien's writing, but here are some that mean a lot to me.

- Death and Loss

In a world with immortal beings, death becomes a curiosity. A dreaded thing that might almost be a relief after the many ages of life. For mortals, death is to be feared, but it is by no means the end of one's journey. The immortal elves live at a distance with the world, while the long-lived Dwarves (never dwarfs) burrow themselves underground, seeking treasure. Only humans can experience a true life because of death.

Whilst this is a predominantly Christian ideology, we learn that death is not the worst thing that can happen. Death is described as a journey onwards:

'the grey rain-curtain turned all to silver glass and was rolled back, and he beheld white shores and beyond them a far green country under a swift sunrise' (The Lord of the Rings, Book 6, The Return of the King, The Grey Havens)

Love, courage, honest toil, friendship, family, art and beauty are what life is about, so worse-than-death can come to the living if they exist without these things. The knowledge of future loss is what makes life, and the time we are 'given', so very precious. Life is bittersweet.

- Small acts and small people have a great effect.

The hero of Lord of the Rings, the real hero, is the gardener, Samwise Gamgee. Fight me.

Sam is a servant, or a lower class to the other Hobbits, and works a menial job, but his honesty of heart and his courage end up saving the day. Not only does he carry the One Ring, but he gives it up, and when Frodo's resolve/body fails, he carries Frodo to the Cracks of Doom.

Pippin and Merry both become war heroes. First providing the impetus for the Ents to go to war, and then, separately, becoming badass warrior hobbits.

Small acts of loyalty, of love and of kindness permeate the writing of Tolkien, and they make the difference, often, between success and failure.

- Power, lust, and wraithing.

Although power and lust can be explicitly seen in the depiction of the (singular) Eye of Sauron, the Ringwraiths - the Nazgûl - are the really terrifying characters in the Lord of the Rings.

Why?

Because they were mortal men, who accepted a gift and became corrupted, just like you or I could be. If we think back to those politicians who sent millions to their deaths in the First World War, or look now at those who enter politics trying to change things for the better, but succumb, gradually, to the interests of the powerful (to the military-industrial complex, to media likeability, to sex, to big money, to fear) then we see the 'wraithing' of those in public office.

Those who succumb to wraithing become servants, forever beholden to the thing that seduced or ensnared them. It is no surprise that the Ring, and power in general, are often spoken of in Tolkien's writings and their depictions like a powerful addiction.

- Ecology and the Natural World as a Force

Nature is as much a character in the Legendarium as Galadriel, Ancalagon the Black or Beorn the Bearman. From his description of the mountains, to the majesty of the forests, Tolkien expresses a deep and profound idealisation and respect, for the natural world.

There are also shades of Tolkien being wary and slightly frightened of nature too There are no better illustrations of this fear than the Ents.

The Ents are tree-herders who have become 'treeish'. They are very old, immensely powerful, and slow in thought and deed...until they get angry.

When Saruman the Wizard decides to industrialise his fortress and create a factory for mutant killers, he rather foolishly starts cutting down the trees of Fangorn forest to feed the fires of his warped industry. The ents decide to...eh...'rewild' the industrialised area.

This scene is really a good indicator of Prof. Tolkien's feelings about the natural world. Anyone who has lived through wildfires, the effects of global warming, or felt the wrath of Mother Nature, might relate.

3. Hope, without guarantees.

As one of the generation of post-WW1 'traumatised' writers who turned to fantasy fiction (another example being C. S. Lewis, who was left for dead in The Battle of the Somme), a fundamental philosophy of Tolkien's writing can be described as 'Hope without guarantees."

What does this mean?

It means that despair is as much a logical as a moral failing. We can never know how things will turn out, nor what the future will hold. Despair is a mistake.

The Elven philosophy of estel goes much further into this, but simply put, hope is the only option when times are bad. If we all act as if there is hope, even the tiniest slither of it, then the chances of success are greater. The Elves linger out of hope, and when all seems dark, the Free-men of Middle Earth decide to go out in a blaze of glory, rather than to sit and anticipate defeat. This is very much a military idea: eyes front, and can really help us in our worst times. There are some things that are worth fighting for, even just hope.

No matter how bad the world gets, and how low our spirits drop there is ALWAYS hope. Stick to the job at hand, carry on, do not succumb to despair. Even if there is a 99.9% chance of failure and defeat, hold on to hope.

4. Love

There are many tales of love in Tolkien's writing. From the friendzone-breaking sweetness of Éowyn and Faramir, to the enduring sacrifice and duty of Aragorn and Arwen Undomiel, to the friendship of Legolas and Gimli, we are given many examples of romantic, platonic, negative and positive love.

Beren and Lúthien

The tragedy of Beren and Lúthien is perhaps the most famous of the love-stories of middle earth. Beren, the mortal warrior who, in defeat, stumbles across the elf-maiden Lúthien, dancing and singing in a glade of hemlock. They fall in love, he instantly, her a little later, and he gives her the nickname Tinúviel (nightingale). When he asks for her hand, her father Thingol, distrustful of the mortal, bids him reclaim one of the stolen silmaril, the hallowed jewels forged at the creation of the earth, an impossible task. Beren overcomes many perils, and succeeds, although is mortally wounded and dies soon after returning with the jewel. Lúthien dies of grief, and in the Halls of Mandos (one of the Founders of the earth) the deity is moved to tears, and allows her to return, with Beren, to life to live as a mortal. Thus the most beautiful and beloved immortal gave up her gift to be with her love, and taste the bittersweet joy of finite, mortal love.

Returning to the letters of Tolkien, we can see the significance of the story of Beren and Lúthien for Tolkien, when describing the grave inscription he has chosen,

"... 'EDITH MARY TOLKIEN 1889-1971 Lúthien': brief and jejune, except for Lúthien, which says more for me than a multitude of words: for she was (and knew she was) my Lúthien...she was the source of the story that... became the chief part of the Silmarillion. It was first conceived in a small woodland glade filled with hemlocks...but the story has gone crooked, and I am left, and I cannot plead before the inexorable Mandos."(Tolkien letter 340 to his son, Christopher, in 1972.)

When John Ronald followed Edith two years later, his inscription was hopefully an easy one to choose. 'Beren'. If that is not romantic, I don't want to know what is.

Sam and Frodo

Frodo and Sam are two dudes who love each other, it's that simple. While Frodo is the 'master' in terms of employment, and Sam is his employee, their relationship is one of the purest expressions of loyalty, of fidelity and of love that exists in the whole Legendarium. We never know the nature of their love: platonic, perhaps romantic? There is evidence of both brotherly and romantic love that one can argue, but in the end, it only matters however it matters to you, the reader...which brings me to:

5. Applicability, not Allegory.

In reasoning out these themes, we come to another proof that Tolkien's work is evergreen, and will continue to enthral and delight new generations of readers for hundreds of years to come: Tolkien's insistence on Applicability over Allegory.

In his own words:

“I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so... I much prefer history – true or feigned– with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.” (Foreword to the Second Edition of Lord of the Rings 1966)

While one generation might see the One Ring as a clear parallel to the nuclear weapons race, a reader fifty years later might see the Ring as being applicable to their own experience with social media, or racism, or mental illness. What the reader applies to the writing from their own perspective means that the books are not just some white man spouting his views but rather a canvas upon which the reader can sketch emotional and thematic connections to their own lives.

Too many writers create a direct allegory to their writing which either dates it, or can seem limiting when trying to engage with the work. Tolkien's insistence on applicability means that whatever you feel that draws connection to the book is correct. It is your own interpretation that matters. This is rare.

6. The concept of 'legendarium' and Fan-Fic

In creating a Legendarium, Tolkien, perhaps jokingly, dreamed of creating a cycle of myths, histories and legends that could be equated to the Greek Pantheon, the Irish Cycles or the Norse mythologies, with other writers adding their art,

"Do not laugh! But one upon a time... I had a mind to make a body of more or less connected legend, ranging from the large...to the level of romantic fairy-story...The Cycles should be linked to a majestic whole, and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama. Absurd." (Tolkien letter 131 to Milton Waldman, 1951)

This is a keen example of Tolkien's generosity of spirit. Some debate how keen he really was to have us non-polyglot geniuses touch his legendarium with our grubby mitts...but they have. There are thousands of works by fan-fiction writers around Tolkien's legendarium, including this one, which is the world's longest piece of fanfiction, currently clocking in at 5,300,000-odd words!

Whilst the Potterheads, the Hungergamers, the Pratcheteers and the many other fandoms enjoy rich, often vividly erotic, fan-fiction catalogues, this surely stands as a testament to the power of Tolkien's fantasy world.

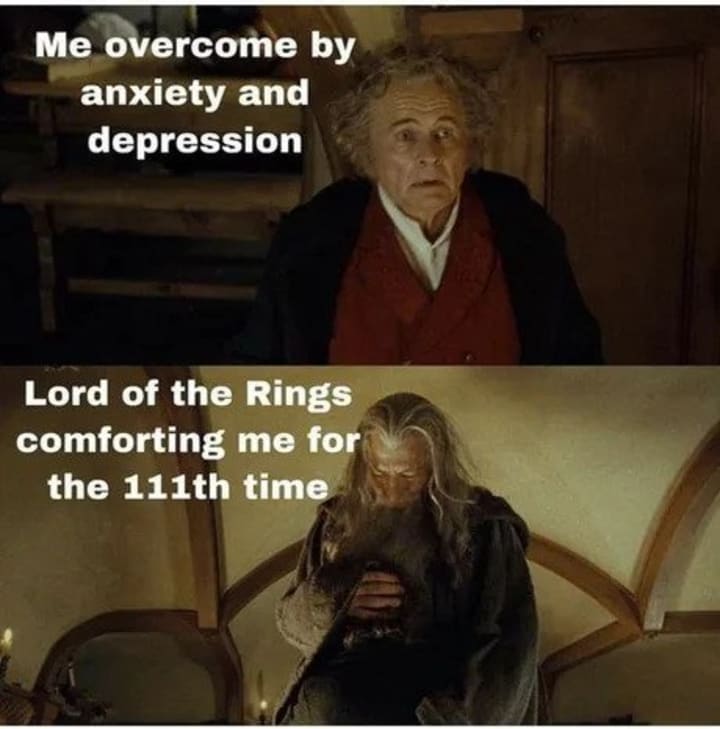

7. How Tolkien and Rob Inglis saved my life

I first read 'The Hobbit' while a young lad, and fell in love Tolkien's writing. Then, I read the Lord of the Rings and became somewhat obsessed. As a bilingual bookworm, and a bit of a loner, I found so many stories within his writing that I could relate to. The movies only added to my love.

Then I went out into the world, and, following some adventures and joy, I started to get very unwell. After several years of trying to find the answers, I received a diagnosis at 22 years old that I was Bipolar. It explained a lot but didn't fix anything.

I grew cold, empty, and embittered as I did battle in my own head. The happy boy became twisted.

After several attempts at suicide, I fell into the sort of depression that can only come with failing to kill oneself. I drank myself nearly to death, I allowed the despair to win, I isolated myself from the world; staying at an elvish distance and a dwarvish depth from those around me. Engaging in romances and friendships with the shadowy non-existence of a wraith.

I never slept well, and in my little grief-hole, I always had the audiobook of Rob Inglis narrating the Lord of the Rings on in the background. I listened to him narrate these tales over and over, hundreds, maybe thousands, of times. They helped me feel less alone and cold when I was depressed, they were calming and relaxing when I was manic.

Eventually the messages that I could apply to Tolkien's writing began to sink in. Despair should never be allowed to win, hope, without guarantee, was the better option. Love, courage, friendship, honesty. It has taken time, but the books definitely saved my own silly life.

I am fortunate that I have not felt suicidal in a long time, but whenever the Black Breath blows on my neck, I listen to the Lord of the Rings audiobooks.

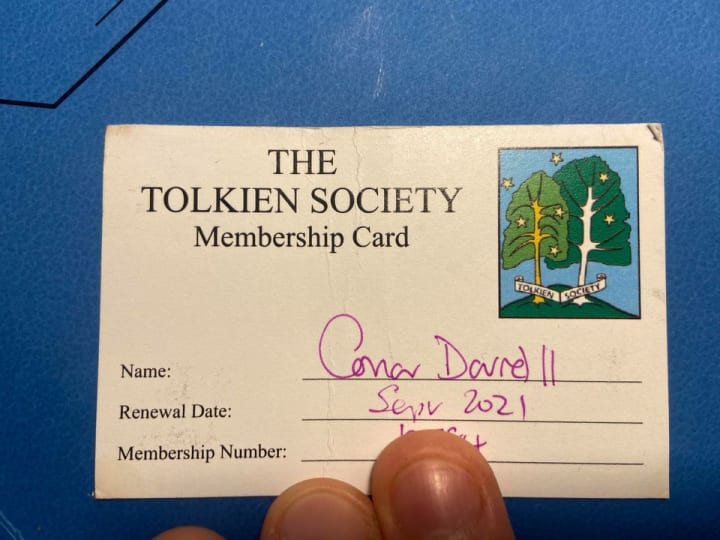

8. The Fandom

Whilst you are now bored of the used to the writer called Conor, I am also called Huanhîr Henluin Estellion. I came up with this name because I am a member of the Tolkien Society, the world's largest fellowship of J.R.R. Tolkien fans.

I joined during lockdown, when the world seemed grim and I thought that perhaps the walls were closing in a bit. I re-read the Hobbit, the LOTR and the Silmarillion, and thought it might be fun to attend a talk or two, to expand my understanding, maybe make a few friends...and then I got sucked in!

The Tolkien Society has given me new friendships, a far greater understanding of the works of JRRT, and helped me to enjoy the world of Tolkien in a way that I never realised before.

As I write this, I am wearing my Oxonmoot t-shirt from our annual gathering in Oxford at the start of September. A long weekend of lectures, games, song, laughter, mischief and a few trips to sample the local ale...

We ended the weekend with the Enyalië, a trip to Wolvercote cemetery in Oxford to pay respects to Professor and Mrs Tolkien. It was an incredibly touching and beautiful occasion, and then we all returned to real life, and dispersed into the winds, richer for the experience of our time together.

As fandoms go, this one takes beating. Be it a local Smial (Tolkien fan-group) or a university reading circle. We are everywhere!

9. Tolkien's influence.

Tolkien has influenced popular culture more than any other fantasy writer, even Rowling.

There I said it.

Whether it's the books of Terry Brooks, the scope of George R R Martin's Game of Thrones, the music of Led Zeppelin or the hobbies of Stephen Colbert, Tolkien has long since established himself as a huge influence on art, dance, music, film and fiction.

(Selador??)

1960's Hippies scrawled anti-authoritarian graffiti on the NY Subway with phrases like 'Frodo Lives' and 'Gandalf for President'. National Lampoon's 'Bored of the Rings' remains one of their most successful parody books. South Park, Family Guy, the Simpsons, and countless other comedy shows have all referenced Lord of the Rings and hobbit-lore. Where nerds exist, the Legendarium does too.

Universities now offer courses in Quenya and Sindarin as electives, Doctoral theses have been written about the legacy of Tolkien's art. People write books decrying him as a post-colonialist dinosaur, other's write books about his diversity and universality. The sheer weight of academic paper that has been written about Tolkien would, ironically, cause the Ents to go to war for destruction of trees.

And there's this. Oh how I would plead before the inexorable Mandos for this to be undone:

Yes, dear reader, that is Spock singing a 'hip' 60's pop hit about Bilbo Baggins...

Namärié

So, my dear reader, I must stop writing. If you have survived the hellish journey to the end of this piece, like a certain pair of Hobbits I could tell you of, then surely you must agree that the fantasy world of Tolkien is not only the most soundly structured and the most thematically rich, but it also has an applicability of spirit that allows the reader to connect to it from their own personal experience, making it evergreen and ever-relevant. It has the largest organised, connected fandom, and the largest fan-fiction following. It is, quite simply, the best fantasy world.

Professor Tolkien created his books to amuse, to delight and to move his readers. He certainly did that.

I bid you namärié (farewell) and hope to see you someday along the road that goes ever on and on.

Viva Los Tolkienistas!

About the Creator

Conor Darrall

Short-stories, poetry and random scribblings. Irish traditional musician, sword student, draoi and strange egg. Bipolar/ADD. Currently querying my novel 'The Forgotten 47' - @conordarrall / www.conordarrall.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.