African Apocalypse: The real ‘heart of darkness’

Joseph Conrad’s classic novella Heart of Darkness – and the film Apocalypse Now – examined colonial brutality. Yet as a new documentary points out, they missed the most crucial voices – those of the victims

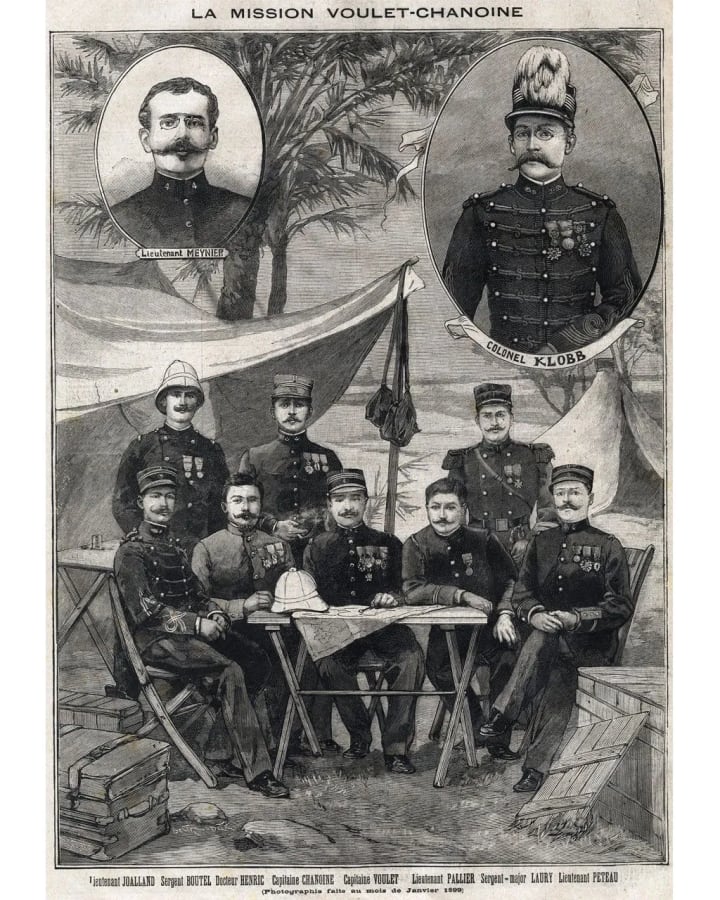

In a year that has sharpened the focus on how Britain’s Imperialist legacy is remembered, the arrival of African Apocalypse seems rather prescient. The documentary – fronted by British-Nigerian poet-activist Femi Nylander and directed by Rob Lemkin – is a nonfiction retelling of the real-life barbarity inflicted on the people of Niger, in West Africa, by a French army captain called Paul Voulet. Taking cues from Joseph Conrad’s classic novella Heart of Darkness, Nylander travelled to the African country to retrace Voulet’s steps for the film and give voice to those still living with the collateral damage of his campaign.

This chance for the Nigerien tribes to share their perspective of the impact of colonial rule was something Conrad never afforded his African characters. “We purposefully went out to make sure that in our film, Africans speak regularly,” Nylander tells BBC Culture. “As they said in the film, ‘No one has ever come before to ask us about our history.’”

Conrad’s novella was first serialised in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in 1899 and is now considered a seminal piece of literature for its brutal critique of European colonialism and the devastating effect it had on African civilisations. Academics, literary critics and readers continue to celebrate the British-Polish author for bravely depicting the horrifying reality of colonialism at a time when it continued to infect the lands on which Europe laid its claim without significant objection from ‘civilised’ society.

His work has proven influential in the understanding of the ‘white man’ at a time when whiteness was the highest form of currency. It is consistently studied at universities and colleges. But while Conrad succeeds in his pejorative portrayal of Imperialism through Kurtz, a man working for a Belgian company who is purposefully given both British and French heritage to represent the entirety of Europe’s despicable campaign of dominion across Africa, he does little to ameliorate the perception of the indigenous people being oppressed.

Skewed vision

In fact, his centering of a European perspective against a foreign backdrop is a frequent occurrence in this literary genre that has years later been criticised for cementing a reductive view of African people. Scholar and author Chinua Achebe noted this in his 1977 essay An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. He argues that Conrad uses “Africa as a metaphysical battlefield devoid of all recognisable humanity, into which the wandering European enters at his peril.”

In European colonial literature, often the indigenous person or group is continually othered by restricting them to the margins of the story – and who they are is solely defined by the white narrator, protagonist or white characters, frequently in negative terms. In the case of Heart of Darkness, that perspective comes from a seaman called Marlow who is sharing the story of his pursuit of Kurtz, a corrupted ivory trader who had gone Awol in the then recently-established Congo Free State (now the Democratic Republic of Congo). “The prehistoric man was cursing us, praying to us, welcoming us – who could tell?” Marlow says, when a tribe of Africans gather on the shore of the Congo river where his steamer is travelling. “We are accustomed to look upon the shackled form of a conquered monster, but there – there you could look at a thing monstrous and free.”

Later, Marlow compares the African ‘savage’ who serves as the fireman on the ship to “a dog in a parody of breeches and a feather hat walking on his hind legs”. It’s these instances that serve to dehumanise the African people, says Adebe. “Can nobody see the preposterous and perverse arrogance in thus reducing Africa to the role of props for the break-up of one petty European mind?” he writes. “But that is not even the point. The real question is the dehumanisation of Africa and Africans which this age-long attitude has fostered and continues to foster in the world.”

Even the final motif of Marlow looking at the darkness of London, which is meant to mirror the darkness he associates with the African territory, suggesting the two continents are one and the same, Conrad brings down Europe to the uncivilised standard in which Africa is held in the West’s perception rather than allowing for the idea that the African way of life is civilised by its own determination of the word. Thus Marlow, and by extension Conrad, never stops seeing the African people as wild savages.

This perception and marginalisation was copied and pasted onto the Vietnamese people by Francis Ford Coppola in Apocalypse Now, which African Apocalypse’s title nods its head to. The film, set during the Vietnam War, follows an American soldier (Captain Willard, played by Martin Sheen) sent into the warzone to take out a rogue colonel. Coppola portrayed Vietnam in the same way as Conrad presented the former Belgian Congo: an endless wilderness filled with savages who use arrows, spears and were primitive enough to be hoodwinked into thinking Marlon Brando’s Colonel Kurtz, like literary Kurtz, was a god-like leader to be worshipped. In reality, these characters were based on the Montagnard (indigenous peoples of the Central Highlands of Vietnam), who had been highly trained by both South Vietnamese and American forces to become allies against the Viet Cong.

By painting one ethnic group with the stereotypical traits of another ethnic group located 10,000km (6,213 miles) away and more than 50 years earlier, Coppola serves up a classic example of Orientalism. This term was coined by Edward W Said in his book of the same name, published a year before the release of Apocalypse Now, which offers a critique of the West’s commonly held view of Africa, Asia and the Middle East as ‘the Orient’, a negative portrayal that continues to be reinforced in the “electronic, post-modern world”.

“Television, the films, and all the media’s resources have forced information into more standardised molds,” Said writes. “So far as the Orient is concerned, standardisation and cultural stereotyping have intensified the hold of the 19th-Century academic and imaginative demonology of ‘the mysterious Orient’.”

Speaking out

African Apocalypse avoids this dehumanisation of the Nigerien people by using Nylander, the film’s Marlow or Willard, as a signal-booster for the stories that have been passed down by the ancestors who survived Voulet’s violent campaign. “Coppola famously said Apocalypse Now wasn’t about the Vietnam War, it is Vietnam – very arrogantly, but like Conrad, he was really only interested in interrogating the soul and the mind of the colonial invader,” says Lemkin. “We’re reversing that because our point of view is completely different because of the way we were working with the communities and the families.”

“They really relished the opportunity to present themselves for an international audience and be able to say, ‘this is what happened to my grandparents, this is what happened in this village and this is how we feel about this today’,” Nylander adds.

Conrad drew from his own experience of the European occupation of the African territory, where for some time he was part of the crew of a steamer traversing the Congo river. But over the years, historians have pointed to the influence of several real-life people for his depiction of his antagonist Kurtz, including Léon Rom, an administrator for Belgian King Leopold, British army officer Edmund Musgrave Barttelot, his associate slave trader Tippu Tip and Henry Morton Stanley, the leader of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition.

It was during a research project related to Heart of Darkness that Nylander came across these barbaric figures and was subsequently introduced to Paul Voulet. He noticed several similarities between Conrad’s Kurtz and the French captain: both were Europeans with an Imperialist superiority complex who were sent to African territories on a mission of conquest but went mad, inevitably ignored orders and used savagery to enforce their power over the indigenous people. But as the documentary points out, Voulet couldn’t have been a direct influence on Conrad’s writing.

“The point about it really is not so much that Kurtz was based on Voulet so much as the idea that as Conrad is writing things, like Kurtz going into the Congolese forest and putting himself up as a tribal guy who was controlling so-called natives, with his quill pen in Kent, Voulet at exactly the same time was doing that in real life,” Lemkin tells BBC Culture. “It’s a sleight of hand in our movie to say, ‘Here’s a guy who it could be. Let’s go off and find it.’ Obviously when we get there, we’re really telling another story.”

“We wanted to say that truth is stranger than fiction,” Nylander adds, “or in some ways more brutal than fiction.” Voulet certainly comes across as a more brutal person than Kurtz. While Conrad implies that his antagonist was a gentle soul before transforming into a tyrant, it’s said that Voulet was chosen by French powers to lead the campaign precisely because of his ruthlessness. “Paul Voulet, the 32-year-old son of a doctor, had, according to his officer colleagues, ‘a true love of blood and cruelty coupled with a sometimes foolish sensitivity,’” writes Sven Lindqvist in his book Exterminate the Brutes.

“So despite, or perhaps thanks to, his reputation, Voulet was appointed head of an expedition that was to explore the area between the Niger and Lake Chad and place it, as was said, ‘under French protection’. Voulet was given a free hand to use the methods for which he had made himself notorious.”

Also, much of Kurtz’s “unspeakable” acts are kept hidden to protect The Company and serve as a metaphor for the way European powers worked hard to keep knowledge of its crimes in Africa away from public scrutiny. “The story is not really in the centre of the story, the story is in the haze around it,” says Lemkin. “You can’t put your finger on it. It’s a metaphor for how people in 1899 felt. The cruellest violence that was going on was going on at the edge of their consciousness and they didn't have to be troubled by that.”

A legacy of trauma

Whereas the documentary allows the descendants of those who witnessed and survived the worst of his brutality to detail their people’s side of the story. These tribal members might not have physically witnessed the worst of Voulet’s atrocities, which included rape, mutilation, torture and mass murder, but the inherited trauma can be understood in each one of the film’s interviews.

A recurring sentiment offered by these talking heads is that Niger will “never forget” the decimation inflicted on their people by European occupation. It’s reminiscent of the widely held promise made by Jewish survivors of the Holocaust to never forget the pain and suffering inflicted on them and their ancestors by the Nazis during World War Two. Culture has played a significant role in ensuring that the world rightly never forgets, with countless books, film and TV shows dedicated to the subject as well as educational systems including the study of the Holocaust in the curriculum. But the same can’t be said for the genocidal acts inflicted on African nations by Europeans, and that’s because the British, French and even Americans who long benefitted from slavery, would be the villains in any narrative on the subject.

“It’s a lot easier for Britain to just ignore that it even has a history there and we have a history written by the victors,” Nylander says. “It’s a way of portraying these nations as forces for good in the world, rather than necessarily interrogating the parts of the history which makes them something very different. And if we start to interrogate this history, then we have to start to interrogate the present continuation in some ways of this history.”

“The violence that was done during imperial times in Africa, in Asia… in South America, is so connected to the way the world is now,” adds Lemkin. “Relatives of my family died in the Holocaust and also died in the potato famine in Ireland, but I can’t really say that it connects to the way the world is now in the same way that the colonisation of Africa and Asia has created the entire economic structure of the current world, which of course is changing.”

The world is changing and there is an increasing demand for more diverse perspectives on history. Heart of Darkness has been adapted countless times since its publication but rarely has the coloniser’s point of view been flipped or expanded to include the viewpoint of the colonised, too. “I don’t think you would really want to make an adaptation of Heart of Darkness now, as a [straight] adaptation,” says Lemkin. “Maybe you would want to do what we did in a non-fiction way, which is to just tip it upside down and shake it about and see what comes out.”

Nylander wants more time and space for formerly colonised regions like the Democratic Republic of Congo and Niger, as well as Vietnam, to share their own histories. “We have the idea that if it’s not written down by some scholar in a European library, then it’s not real,” he says. “What we need to do, especially now that we have the ability to do things like films and document things in other ways, is start to look more into these oral histories and tease out the truth of what happened in these areas rather than continue with the same trope that there’s no history if it wasn’t written down by a European in some point in the distant past.”

About the Creator

Cindy Dory

When you think, act like a wise man; but when you speak, act like a common man.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.